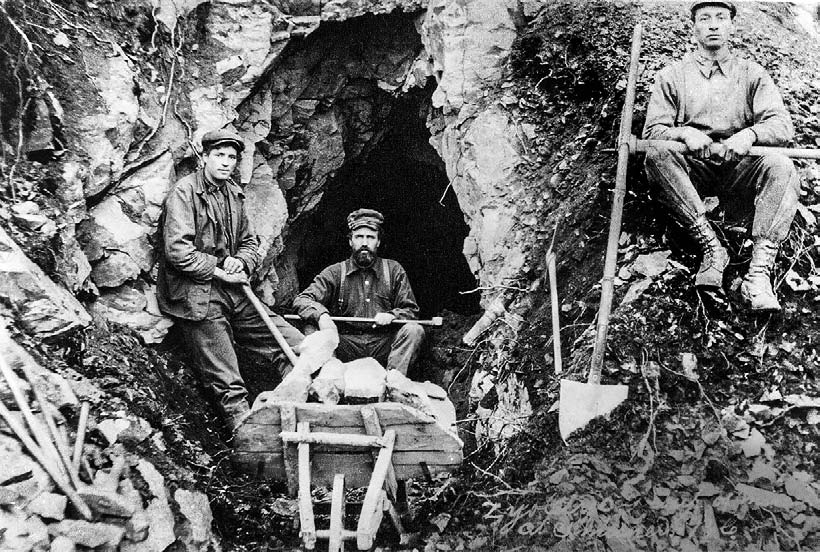

Who were the early prospectors and miners in the Bulkley Valley and what was it like? Although many prospectors were mining and gold rush followers who had worked their various ways up from the States and other parts of the world, some were natives born in this area.

The Pioneer Prospector

One of the first prospectors was William Binnie “Tom” Forrest, who died in Hazelton in 1923 at the age of 83. The Interior News of September 26, 1923, described him as “the last remaining member of the early band of pioneer prospectors in this section” and went on to report that Forrest staked the first mineral claims in the Bulkley Valley, on Hudson Bay Mountain and on Dome Mountain, in 1898. Not only had he lived “an honest and straightforward life,” but also, “…today, the intense prospecting and development is carried on with greater ease because of the trails blazed and built by the departed pioneer on Dome Mountain.” About 16,800 ounces of gold were recovered from gold veins on Dome Mountain in the early 1990s and the mine is being readied for production again.

A Well-Earned Payday

J.J. Herman was a well-known Smithers businessman who, in 1936, made a deal with Tommy King on the Little Joe prospect in the Babine Mountains. The little mine was well above tree line and the upper part of the trail was cut across a talus slope. Herman mined and sorted ore by hand, seven to eight sacks per day.

Joe “Kicker” Kelly (Kelly’s Cave), a colourful Smithers prospector, helped sort and bag the ore. Kelly, who had made his way up here from Kentucky about 1914, was a good horse-packer and a cook. “We ate a lot of beans,” laughed J.J. Ben Nelson.

Emery Tomkins took out the ore with packhorses by way of the trail to Sunny Point and then the Driftwood Creek road to Smithers. The ore then went by rail to the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company smelter at Trail, B.C. But it was late in the season by the time they were ready to ship and they were having some awful snowstorms. Herman had vivid memories of the horses coming up the mountain along the narrow rocky trail in a blizzard, led by an old pinto. When the eight packhorses arrived at the mine, each horse was loaded with two sacks of ore quickly secured with a barrel hitch, and then back down the mountain they went. They came up every other day, so the horses got a rest.

The weather got so bad that Herman and Kelly did not know if the horses could get in for the last shipment or not. They were just bagging the last bit of ore when they saw the horses down below, barely visible through the falling snow. “I never saw something that looked so welcome,” Herman recalled. When the packers arrived, they all went into the mine, around a corner in the dark, with their miner’s lights on. They ate their lunches in a festive mood; it was a little farewell party. Then they went back out to the horses in the snow. Much of the trail was already blown over, and they had old Pinto take the lead. He had a hard job but he was able to nose around, find the trail, and lead them down the mountain and home for the winter. The ore shipment of five tons assayed 320.5 ounces per ton silver, 0.64 ounces per ton gold, 8.7 per cent copper, 3.1 per cent lead and 5.5 per cent zinc.

War Hero

John “Jack” MacKendrick (Mount McKendrick, McKendrick Creek) came from Campbellton, N.B., and worked on his gold quartz claims in the southern Babine Mountains on the mountain that now bears his slightly misspelled name. In February 1916, he joined the 102nd (Comox-Atlin) Battalion of the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force in Telkwa and was sent to France. He was killed in action on the first day of the battle for Vimy Ridge.

The Second-Generation Prospector and Miner

David Dennis (Dennis Lake) did a lot of packing for various mining companies in the early days and he also was a prospector. When he was a youngster, he went with his father to a locality in the Hudson Bay Mountain area where they dug out small amounts of native (metallic) copper for use as bullets in their muzzle-loader. Dennis remembered that he was 16 years old when he saw his first white man.

Rags to Riches and Back Again

Charles Gordon “Peavine” Harvey (Harvey Mountain) was born in Ohio and left for the mining camps of the American west in 1870, at the age of 16. For several happy years he followed various mining rushes before he and a partner spotted a good gold prospect in Mexico. In order to get a lease from the landowner, they had to trek to Mexico City – a 2,400-kilometre round-trip on saddle horses. After about a year of mining, they had made $15,000, a good stake in the late 1800s. Harvey spent the following winter and his money in San Francisco drinking a lot of good whiskey and smoking a lot of 25-cent cigars. “Them were good cigars, boy,” he used to say.

Harvey subsequently made his way up to the Boundary country and then to Hazelton where he operated a hotel and a real estate business for a few years, went into debt, and married a woman named Katherine. In 1903, they homesteaded what became the Cronin/ Chapman ranch at Glentanna. By 1905, he had claims on the mountain that now carries his name. He and Katherine finally developed a small farm along Driftwood Creek and he worked on his high-grade copper showings on Harvey Mountain. He shipped some good ore with the help of Tyee David and others, but the first proceeds went to repay debts incurred by his hotel business. He later optioned his claims several times, but nothing came of them. Mr. S.A.D. “Sad” Davis, representing Seattle interests, was among the optionees.

Katherine was an accomplished Englishwoman who played the piano very well. She raised goats and was working on a book about farming with goats, but her typed manuscript was lost in a house fire. She also had a serious interest in politics and subscribed to Hansard, the official record of parliamentary debates.

Their son, Gordon, eventually donated the best exposures of the Driftwood Creek fossil beds to the provincial government, which established the Driftwood Canyon Provincial Park on the land.

Prospector’s Idyll

Donald Simpson (Simpson Creek) staked his Victory claims on the west side of Hudson Bay Mountain about 1906, and the Empire claims on the southwest side of the mountain he staked with his brother in 1908. Silver-rich ore was shipped from both properties, but the Victory was the best of the two and the claims are still owned by the family. A letter written by Mrs. Simpson, now kept in the Bulkley Valley Museum, describes the Victory as “the loveliest place” with its profusion of wild flowers, berries, birds and small animals. They lived in the “wee cabin” that Simpson had built, and she brought her violin.

The Optimistic Kids

The Jennings Brothers, Duncan and Dave, known as “the optimistic kids,” walked to Aldermere from Hazelton in 1910. Duncan kept a diary. They started a store/post office and road house at Lake Kathlyn, and much of their business was with the Hudson Bay Mountain Mining Company, which was working at Glacier Gulch. When war was declared in 1914, the mining company shut down, and the Jennings’ business collapsed. They then turned to another type of mining – cutting ice in Lake Kathlyn for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway Company.

The brothers also worked on, and then optioned, their Lone Star claim southwest of Lake Kathlyn. The option was soon dropped and Duncan Jennings left the claim “with a resolve never to return to pound a drill.” In 1917, he joined the army and returned unharmed the next year, and he was soon prospecting again with “Pop” Smith and George Ballard. He and Ballard shipped five tons of ore from the Canyon Group but, Duncan Jennings wrote, “This is no poor man’s country in the mining game,” as he experienced the costs of putting a small mine into production and shipping the ore.

Some “Damned Good Ore”

Axel Elmsted (Mount Elmsted) was born in Jutland, Denmark. He came to Canada as a young man and arrived up here in 1913. He and Tommy Haigh discovered the Big Onion copper-molybdenum prospect on Astlais Mountain east of Smithers in 1917. They had noticed rusty rocks associated with the deposit from the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway where they were working. He and Haigh drove two short adits into the mountain in the early 1920s. Haigh lost interest about 1928 and Ben Mueller stepped in as partner. Elmsted and Mueller did about 400 feet of underground work during the winter of 1929–30, all with handheld drill steel. Subsequent work revealed that the Big Onion is a large, low-grade copper deposit. It is still being explored. Elmsted also leased the Little Joe mine in 1938 and shipped out six tons of “damned good ore” by packhorse. He probably worked on every mining prospect known in the Babine range over his long career, as well as some on Hudson Bay Mountain. He was known to have said that, if he had to start all over, he would go prospecting again.

We have had a glimpse into the lives of a few of our old timers. Most of their stories and some of their names have been lost, but here and there something has survived. Let’s tip our hats to all of them. Better yet, have a drink in their honour when you next have a chance.