Reclamation Guide for Mineral Exploration

Introduction

This online guidance document is designed to support AME members with planning, designing and implementing reclamation activities for exploration projects. While reclamation has long been a requirement in British Columbia and elsewhere, the importance of reclamation and the expectations by government and the public that land disturbances are effectively reclaimed has only increased. In addition, the release of a reclamation bond calculator for mineral exploration by the BC Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources in 2018 has put more emphasis on planning exploration activities that minimize disturbance and therefore limit the amount of the required bond.

The first version of this guide, released in the summer of 2020, focuses on access roads and trails, drill sites and trenches. Future versions will expand from there. The guide has three main sections: planning for reclamation; carrying out exploration; and undertaking reclamation. In some ways the planning section is probably the most important. A well-designed plan will ensure that exploration activities are undertaken in a way that facilitates reclamation once the program is done.

The guide is primarily designed to meet reclamation requirements for exploration projects in British Columbia, but much of the content is transferrable to other areas in Canada and around the world.

In keeping with the focus on British Columbia, the guide has made extensive use of material from the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in British Columbia that was developed by AME, the Mining Association of BC and the BC Government and published in 2008. This is an excellent resource that should be consulted along with this guide. In addition, the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia is reference throughout this guide. The Code along with the Mines Act outlines the regulatory requirements for exploration projects and mines in BC, including the requirements for reclamation.

Acknowledgements

The development of this tool was managed by Rob Stevens, Vice President at AME and was guided by members of the Social and Environmental Sustainability Committee and the Health and Safety Committee (formerly the Environment, Health and Safety Committee). AME would like to thank Erin O’Brien, Deb Bryant, Katherine Gizikoff, Maria Gabriel and Marke Wong for early discussions about the tool and for generating ideas around the content and layout. Keefer Ecological Services, in particular Mike Keefer and Jessica Lowey, are thanked for developing much of the content for the tool and for critical reviews. Mike Choi, Michelle Tanguay, Stephanie Tissot and Jonathan Buchanan are thanked for helpful reviews. AME would also like to thank everyone who contributed photos and images for the guide. The photos are critical for visualizing reclamation activities and leading practices. Finally, the authors and contributors to the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in British Columbia are thanked for developing an excellent resource that was drawn upon extensively for the material contained in this guide.

Disclaimer

The information in this guide presents current best management practices for the reclamation of mineral exploration sites that would apply in British Columbia and other similar jurisdictions. It does not cover all regulatory requirements nor is it a substitute for professional advice as needed. The content of this guide should be considered in conjunction with the regulatory requirements stipulated in the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia (or similar regulation in other jurisdictions) and in permit conditions. The BC Mines Act, the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia, conditions of a Notice of Work authorization and the requirements of an Inspector of Mines will take precedence over the material in this guide.

Planning for Reclamation

Initiating reclamation planning at the start of the exploration project is essential to a successful reclamation program.

Effective planning is key to any successful exploration program. Part of that planning is designing reclamation activities that will restore areas disturbed during exploration.

- Planning exploration in such a way that minimizes environmental disturbance will reduce the reclamation bond amount and overall cost of exploration.

Effective planning can help minimize environmental risks associated with the project while also accelerating the permitting process. Mineral exploration projects should strive to meet the principles of sustainable development; this includes reclaiming land used during exploration back to its natural setting or another acceptable land use that is supported by communities and approved by regulators.

Planning starts with understanding the environment of the proposed project area (the baseline condition) and the activities that are likely to be undertaken during exploration (e.g., trenching, drilling and road/trail building/excavation). That should be followed by applying the environmental mitigation hierarchy such that environmental impacts are avoided or minimized as the first option. This will limit the environmental liability and reduce the overall bond amount for an exploration project. Other factors such as timing of operations, using existing access roads, choosing the right equipment and following regulatory requirements will help lead to successful exploration projects that include effective reclamation of the site.

A valuable resource for proponents to consult is the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in British Columbia produced by AME, the Mining Association of BC and the BC Government. The intent of the handbook is to provide assistance to the mineral and coal exploration sector to ensure exploration activities are planned and implemented with due regard to worker health and safety and protection of the environment and meet the requirements of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia.

What is Reclamation and Ecological Restoration?

Ecological restoration is the process of assisting, through intentional human activity, the accelerated recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged or destroyed toward a sustainable ecological trajectory or pathway (see the Society for Ecological Restoration website here: https://www.ser-rrc.org/what-is-ecological-restoration/). Ecological restoration provides a way of slowing, halting or reversing ecosystem degradation. Ecosystems are dynamic communities of plants, animals and microorganisms interacting with their physical environment as a functional unit. A good source of information on ecological restoration can be found in the publication Ecological Restoration Guidelines For British Columbia.

Reclamation is the process of restoring or returning disturbed land to a natural or other viable state and is the term used in the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia. For mineral exploration in BC, reclamation generally involves ecological restoration of the disturbed lands, but could involve transitioning to other uses depending on the input from communities, Indigenous groups and the province.

Reclamation in mineral exploration usually involve four steps:

- Ground preparation, recontouring and stabilization of slopes and drainage systems.

- Replacing topsoil, organic matter and woody debris that were salvaged and stockpile before and during mineral exploration.

- Revegetation and seeding (if needed).

- Monitoring to ensure reclamation objectives have been met.

Reclamation and Environmental Mitigation

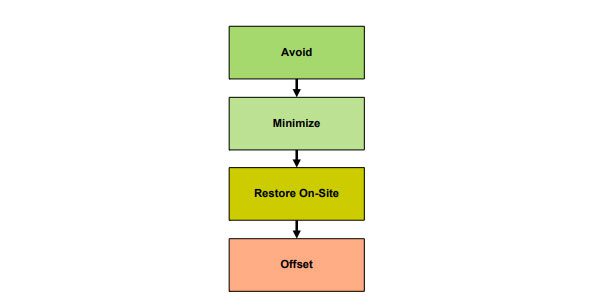

Planning for exploration and reclamation should follow the principles outlined in the Environmental Mitigation Policy for BC. That is:

Avoid, minimize, restore and offset environmental impacts (in that order).

It is usually more economical and efficient to conserve existing environmental values by avoiding or minimizing impacts than to implement restoration and offsetting strategies. The Environmental Mitigation Policy offers a valuable means of considering how to reduce potential environmental effects associated with an exploration project; following this line of thinking should assist proponents in conversations with regulators and Indigenous communities. While the policy is aimed at large projects that are bigger than many exploration projects, it serves as a good tool to review when planning for reclamation.

Online Tools Used for Planning Reclamation

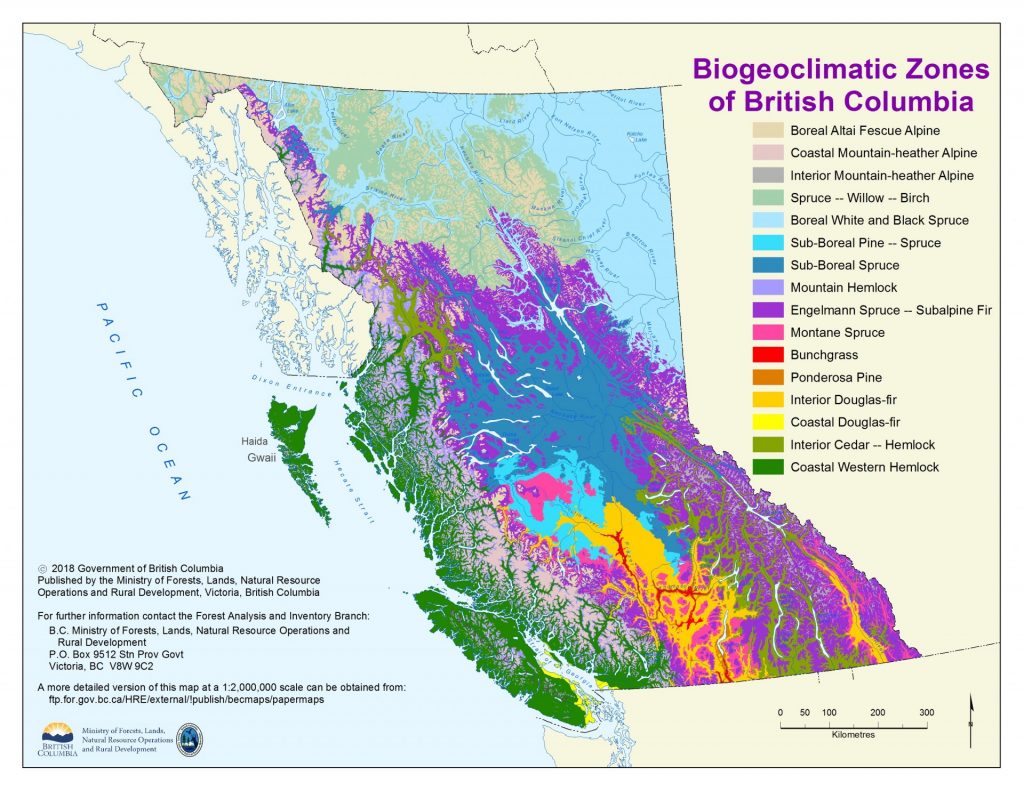

Knowledge and understanding of climatic conditions and vegetation types that characterize an exploration site are important for reclamation planning and permitting in BC. Publicly available online tools such as the Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification (BEC), BC Species and Ecosystem Explorer and iMapBC provide information about climatic zones and wildlife species (at risk, protected or otherwise) based on conservation status or ecosystem classification, which can help to detect environmental values in a particular area based on ecosystem mapping methods.

- Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification (BEC): a provincial ecosystem mapping tool maintained and updated by the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development (FLNRORD). From this website you can access map products and field guides that help in the classification and identification of ecosystems for regions across BC. The BEC system has also developed stocking standards that provide detailed information about the accepted species to be used and the density of planting (e.g. stems per hectare). While these standards are primarily for large areas of disturbance, they can provide helpful information for explorers. Although it is recommended that explorers use consultants who are familiar with the field-use and application of BEC stocking standards. As of March 2020, the most up to date version of the BC stocking standards can be found here (current to March 2019).

- BC Species and Ecosystem Explorer: a provincial database maintained by the BC Conservation Data Centre (BC CDC) that provides approximate known locations of provincial or federal species at risk (plants and wildlife). For example, if a proponent wanted to know if a project area might contain known occurrences of endangered whitebark pine, this database would be the place to look.

- iMapBC: a free provincial mapping service that gives the public access to government databases including administrative boundaries; resource roads, agriculture; climate; archaeology; fish and wildlife species; wildlife habitat areas; ungulate ranges; forest, grassland and wetland ecosystems; geology and soils; land ownership and status; fresh water; land use plans; permits and licenses including Notice of Work and physical infrastructure. Much of the required background information to be contained within a Notice of Work permit application can be found using iMapBC.

- Invasive Alien Plant Program (IAPP) Database and Map: a free invasive plant map and database that can be used by anyone to develop and deliver an effective invasive plant management program in BC. The database contains invasive plant surveys, treatments and activity plans for the entire province. The data is entered by a wide variety of user groups on an ongoing basis. Accessing this database requires permission and a business BCeID. The Invasive Species Council of BC also has a wealth of information about identifying, managing and treating invasive species.

- Explore by Location Tool: BC’s Natural Resources Online Services offers the Explore by Location tool that provides good information on the state and use of the land, including First Nation Consultative Areas, recreational uses, trap lines and guide outfitter tenures, crown land reserves, forest licenses and roads, old growth management areas, grazing tenures and ungulate winter ranges. However, the Explore by Location tool lacks the BEC mapping data (ecosystem data), soil mapping data, some wildlife habitat data and fisheries data (e.g. fish bearing streams).

Reclamation Planning Using Site Characteristics and a Field Visit

Field visits undertaken during the planning process can help identify areas within the project that should be avoided (such as wetlands, sensitive ecological areas or fish-bearing streams) and can help in selecting drill site locations, access routes and camp locations that will have the least impact on the environment.

The site characteristics of every project are different including aspects such as vegetation, slope, wildlife habitat and of course geology. Many of these characteristics can be determined through available online resources, but not all. A field visit to assess streams, wetlands, slope characteristics and vegetation can support the preparation and efficient review of a Notice of Work permit application. For example, in some cases, even when online resources indicate that a stream is non-fish-bearing, a mines inspector may request that a qualified professional confirm that this is the case, given the limitations of the publicly available online data. As such surveying and assessing streams to determine the presence/absence of fish in advance of exploration access planning and permitting can help with assessing the costs of exploration (and bonding).

- If fish-bearing streams or other features such as critical wildlife habitat, old growth management areas, or riparian areas cannot be avoided through ground-based exploration activities, helicopter-based exploration may provide a cheaper, and thus, more practical option.

- Other planning considerations that may reduce site-specific impacts include relocating drill holes, drilling more than one hole per drill site/pad or realigning trenches to avoid sensitive environmental features (including length, width, and depth), where practicable.

Exploring in Caribou Habitat

All caribou in BC are Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus). There are four designated units (DU); southern mountain caribou, central mountain caribou, northern mountain caribou and boreal caribou. Each of these separate units have distinct life history requirements and utilize habitat in unique ways. The designated units are broken down into fifty-four herds.

It is best to screen for caribou designated units, herds, designation ungulate winter ranges (UWRs) and designated habitat areas (WHAs) prior to commencing project planning and reclamation plan development. Geographically referenced information about caribou distribution and habitat designations is available in iMapBC. The specific constraints on industrial activity in some areas will inform the timing and implementation of exploration as well as influence the reclamation requirements. These vary for each designated caribou unit. In some areas, there will be a requirement to submit a comprehensive Caribou Mitigation and Monitoring Plan specific to work in identified critical habitat areas (South Peace Northern Caribou). If you are uncertain if your Notice of Work and supporting Reclamation Plan will require caribou specific content, discuss it with your inspector or contact the regional Ministry of Energy Mines and Petroleum Resources office for confirmation.

Wildlife habitat overlaps within a project can be one of the determining factors in how a site is reclaimed. Although mineral exploration is often exempt from the general wildlife measures (e.g., reclamation, stand stocking/retention) specified in an Ungulate Winter Range or Wildlife Habitat Area orders, within certain designations, especially those which include caribou habitat, full reclamation is expected of all roads, trails, drill pads, or drill sites. This typically includes permit conditions that specify careful measures to address caribou habitat management. management of invasive species, rough and loose surface preparation (on recontoured, fully reclaimed road surfaces), planting of conifers according to the stocking standards for the pre-disturbance ecosystem (determined through biogeoclimatic (BEC) ecosystem mapping) and the planting of alder seed.

The mitigation and reclamation activities will vary according to the caribou lifecycle habitat use identified by the designated unit, the proximity or overlap with Ungulate Winter Range or Wildlife Habitat Area, the terrain and the pre-disturbance ecosystem. The mitigation hierarchy in BC’s Environmental Mitigation Policy is best used for planning exploration and reclamation within caribou habitat: Avoid, Minimize, Restore and Offset. Examples of potential mitigation and reclamation measures include;

- Avoid: relocate activities outside winter habitat area; conduct activities within timing windows to avoid calving and rutting periods; use consistent flight paths along river valleys; conduct exploration by air rather than constructing roads; identify and avoid key habitat features such as mineral licks; plan around large mature tree stands; concentrate activities spatially and temporally.

- Minimize: manage for invasive species; construct roads with dog-legs to minimize line of sight; design access to minimize long straight linear corridors through forested areas; leave shrub bands along the linear corridor; place line of sight blocks using woody debris/rollback/tree bending; minimize the removal of large-diameter trees; minimizing root mat disturbance to expedite site re-vegetation; maintain an altitude of 300m or more for helicopter and fixed-wing traffic; backfill/recontour trenches to a stable angle of repose to minimize risk of entrapment; use smallest and lightest equipment practicable to minimize surface compaction; commit to a stop-work order if caribou are within 1000m of an active work area.

- Restore: plant/transplant seedlings to speed re-vegetation within linear disturbances; construct earthen berms; use fertilizer treatments to speed re-vegetation; use woody debris to close linear site-lines; create re-vegetation micro-sites using mounding, ripping or scarification.

- Offset: offsetting with offsite habitat or through financial mechanisms is not commonly used to address mineral exploration disturbances to caribou but there is an offsetting process identified within the Guidance for the Development of Caribou Mitigation and Monitoring Plans for the South Peace Northern Caribou which provides an example.

Assessment of End Land Use

An important step in reclamation planning requires identification of the current land use (i.e. pre-exploration) as well as a suitable end land use (i.e. post-exploration) while taking into consideration previous and potential social, economic, environmental and natural objectives.

- In BC, exploration projects are typically located on natural lands in backcountry areas so forestry, Indigenous uses and values, recreation and wildlife are among the key perspectives to consider.

On occasion, projects may interact with rural acreages, agricultural land and other uses such as overlapping industry. Understanding past and current uses greatly facilitates the planning stages of reclamation.

In most cases, reclamation in mineral exploration will involve restoring the natural setting of the site. The Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia also reflects this approach as section 9.13.1(4) specifies that exploration sites must be revegetated to a self-sustaining state with species appropriate for the site. Seeding of rapidly growing agronomic species with fertilizer treatments to accelerate revegetation used to be the dominant practice for reclamation. Reclamation is seeing a shift away from agronomic plants to the use of native species. Many agronomic species can be persistent at a site which prevents natural revegetation and attracts wildlife. This may have implications on the close out of the reclamation bond if it appears likely that natural revegetation may not take place. However, in some cases uses of non-persistent agronomic species, such as fall rye, can help to stabilize the soil and prevent erosion while natural revegetation gradually takes hold.

Reclamation Plan and Objectives

It is recommended that each exploration program have an overarching, standalone reclamation plan for the entire proposed exploration program that covers all proposed activities and disturbance.

A standalone reclamation plan facilitates the review of permit applications by the mine inspectors, Indigenous groups, and referral agencies. Such an overarching reclamation plan can be provided as a separate attachment with your Notice of Work application and should complement and summarize the information provided in each activity section of the Notice of Work application.

A reclamation plan should clearly outline how a proponent will restore the areas used temporarily for exploration purposes to an acceptable end land use by ensuring:

- Long-term stability and erosion control of the post-exploration landforms and watercourses.

- Restoration of habitat, ecosystems, and biodiversity that approximates the original conditions.

- Protection of water quality.

- Removal of all buildings, equipment, materials and refuse.

- Remediation of any contaminated areas.

A thorough description and documentation (field data and before/after photos) of baseline conditions, reclamation objectives and results of reclamation will help focus and rationalize the proposed reclamation activities.

An important part of a reclamation plan is to define and articulate the reclamation objectives for the program. Reclamation objectives set out the long-term goals for reclamation of the site and describe what reclamation activities aim to achieve. They can range from overarching objectives (or principles), such as to return the site to a self-sustaining natural setting, to specific objectives such as to prepare the disturbed ground for natural revegetation. Objectives should be as specific and measurable as possible to allow for the verification that reclamation objectives have been met. They should also have completion criteria in order to measure the objective. For example, the objective to prepare the disturbed ground for natural revegetation could have completion criteria that includes, replacing topsoil, making it rough and loose, and covering with timber and coarse woody debris. Once these activities have been completed, the objective would be met. The Guidelines for the Closure and Reclamation of Advanced Mineral Exploration and Mine Sites in the Northwest Territories provide a good outline of defining objectives for reclamation and mine closure.

Reclamation objectives for mineral exploration are generally related to physical work, but they can also relate to regulatory or social aspects of the program. For example, one objective could be to achieve regulator compliance for reclamation and this is measured by successful closure of the permit and return of the reclamation bond. The Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada’s e3 Plus guide provides a good outline of reclamation objectives for mineral exploration.

A reclamation plan (whether provided in each activity section of the Notice of Work application and/or as a standalone plan) may also need to consider and describe the following:

- A commitment for timely reclamation of work sites and access trails prior to the end of the work authorization date including an approximate schedule of events with timeline.

- Removal or dispersion of fill used to level sites such as helicopter pads or drill pads.

- Decompaction of staging and camp areas.

- Process for securely plugging and capping drill collars to prevent potential discharging of water in the future.

- Process for removing and separating topsoil, subsoil and overburden to ensure they will be stored appropriately to be available for proper use/replacement when reclamation is underway.

- Recontouring of slopes back to the original landforms.

- Revegetation (seeding or planting) with self-sustaining local species to ensure more successful reclamation to end land use.

- Dealing with cleared timber appropriately (e.g. limb, buck and scatter across work sites or access trails).

- Deactivating modified access roads and trails, and full reclamation of new roads and trails.

- Restoring riparian habitat around stream crossings.

Once permits are obtained, mineral exploration projects are required to submit an annual summary of exploration activities to maintain compliance with their permit and with the requirements of the Mines Act and the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia (section 9.2.1(3)). The annual summary outlines the work that was completed, the nature and extent of any disturbances and the areas that have been reclaimed. Details and necessary forms can be accessed here.

Documenting Reclamation Activities

All aspects of the reclamation process should be documented in writing and with photos (or videos). This will support the eventual request to closeout a Notice of Work permit and the accompanying reclamation bonds. It is important to include documentation as part of planning so pre-disturbance site conditions are documented before exploration starts.

Photos of the site are probably the most important documentation that should be recorded. This should include photos from several vantage points taken before, during and after exploration and once reclamation is complete. Ideally the same vantage points should be used during each phase of activities so the extent of the impact and results of reclamation can be clearly seen.

Types of documentation that should be maintained and that would normally be included in the reclamation plan include:

- Baseline environmental conditions and studies.

- Inventory of pre-existing disturbance that may be exempt from reclamation.

- Dates when disturbance occurred and when reclamation was started and completed.

- Equipment used to conduct reclamation.

- Estimations of the area of disturbance (including number of sites (trenches, test pits, surface drilling), length of roads/trails developed, reclaimed areas, timber volumes cut).

- Full descriptions of each reclamation activity, how it meets the reclamation objectives for the site that were included in the reclamation plan, as well as details of compliance with any permit requirements and with the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia. Examples include:

- How the surfaces were prepared and stabilized.

- How stockpiled organic material and woody debris were used in reclamation.

- How access road, stream crossing, trenches, drill holes, camps and other features were reclaimed and stabilized.

- Removal or disposal of any structures and materials that were brought to the site.

- Any monitoring or follow-up plans.

- Training documentation for site personnel and contractors in regard to management of environmental aspects of the program and measures to minimize environmental disturbance.

- All correspondence and consultation with Indigenous groups, communities and government regulators.

Other considerations for documenting reclamation work on a site may include:

- Documenting spill response, the clean up of spills associated with equipment and fuelling infrastructure on site.

- Inventory of invasive plant species over time.

- Assessment of trajectory towards end land use objectives.

- Metal leaching/acid rock drainage (ML/ARD) characterization and waste management.

- Results of surface water sampling.

- Erosion and sediment control management outcomes.

- Documentation of the removal of structures and equipment.

Selection of Equipment to Minimize Impact

Consider reclamation requirements and impacts when selecting the mechanized equipment to conduct mineral exploration activities. Ensure equipment operators are experienced and have specific expertise working in the terrain and ecosystem of your project.

With very few exceptions the best mechanised equipment for the project is the smallest and lightest that will be capable of supporting and completing the work. Evaluate, in consultation with your equipment contractor, if applicable, all the specific tasks the equipment will be required to do, including reclamation tasks. Size (strength), versality (availability of attachments) and rotational range required will be specific to the terrain and ground-disturbing activities planned.

Consider whether a larger piece of equipment such as an excavator is required or whether a backhoe will meet the needs of the project. If the project requires helicopter portable equipment, ensure that the lifting capacity of the helicopter aligns with the weight of the equipment. Excavators and bulldozers are available in many sizes, the machine selection should match the scale of your project and be as small as practical.

Evaluate what multi-attachment flexibility is the best fit for the project and reclamation. Complex work such as the placement of trees into a road corridor, drill pad building in scree or addressing ground compaction will require specific attachments, constrained tail swing and rotational range.

Tracked equipment provides better traction and produces less ground disturbance than wheeled equipment due to lower ground pressure. While wheeled equipment has considerable faster transport times, it has more limited application and works best in packed, firm soil conditions.

Excavators or backhoes rather than bulldozers should be used for roadbuilding and trenching where practicable. This will allow selective stripping of surface soils and placement of material in a location where it will be available for reclamation once work is complete. When reclaiming a trail, road, drill pad or drill site, removing compaction and creating a rough and loose surface is critical to promoting the re-establishment of vegetation and the development of a desired end land use and the reinstatement of pre-development land capability. Decompaction of a surface is accomplished using a dozer equipped with appropriate ripper, shanks or subsoilers.

- When possible, work with companies and equipment owners with a reputation for having well-maintained machines and skilled operators. Request documentation to support mineral exploration and reclamation project experience from the equipment operator or equipment contracting company. Equipment operators with experience in the terrain and biogeoclimatic ecosystems will minimize disturbance and be capable of performing complex detailed work efficiently and effectively.

- To minimize remediation efforts associated with heavy equipment use, include minimum operator experience, equipment routine maintenance, pre-operation inspections, fuelling protocols and the supply of spill kits into equipment contracting agreements.

- The equipment used for personnel transport throughout an exploration site will also influence the efforts required for reclamation. If possible, use small light personnel vehicles such as ATV, snowmobiles or side-by-sides rather than large trucks.

Planning Site Access (Trails and Roads)

Use existing roads whenever possible, and minimize or avoid all stream crossings, riparian areas, steep slopes, wetlands, old growth forest and other sensitive ecological areas. Consider the use of a helicopters for site access if these areas cannot be avoided.

Minimizing the infrastructure footprint should guide the planning and construction of linear features such as trails and roads; this includes optimization of route planning to limit lengths and widths of trail and roads.

Reclamation requirements of trails and roads will differ between sites, depending on other site-specific overlaps like ungulate winter ranges and caribou habitat, and the type of road and its future use. The requirements can range from deactivation (partial reclamation) to full reclamation, with full reclamation typically being required on more sensitive sites (e.g. wildlife habitats for species at risk) or for newly constructed trails and access roads that are not required beyond the term of the permit (e.g. up to five years).

- Section 9.10.1(7) of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia specifies that reclamation of exploration access features requires the restoration of drainage patterns, removal of bridge and culvert structures, a stable surface that minimizes future erosion and the establishment of self-sustaining vegetation appropriate for the site which may include reforestation (as directed by an inspector).

Partial reclamation, or deactivation, of exploration access trails and roads involves the removal of most culverts, digging additional cross ditches and pulling back potentially unstable road sections, but often leaving major crossings like bridges in place. Deactivation/partial reclamation still allows the road to be passable by vehicles. An good resource on road deactivation techniques can be found in the BC government’s Engineering Manual for resource roads.

Full reclamation of exploration access trails and roads, if required or desired, involves the removal of all culverts, bridges, pulling back unstable and potentially unstable road shoulders and fill slopes, installing water bars and de-compacting the road surface to permit water infiltration and vegetation growth.

Types of Access Roads

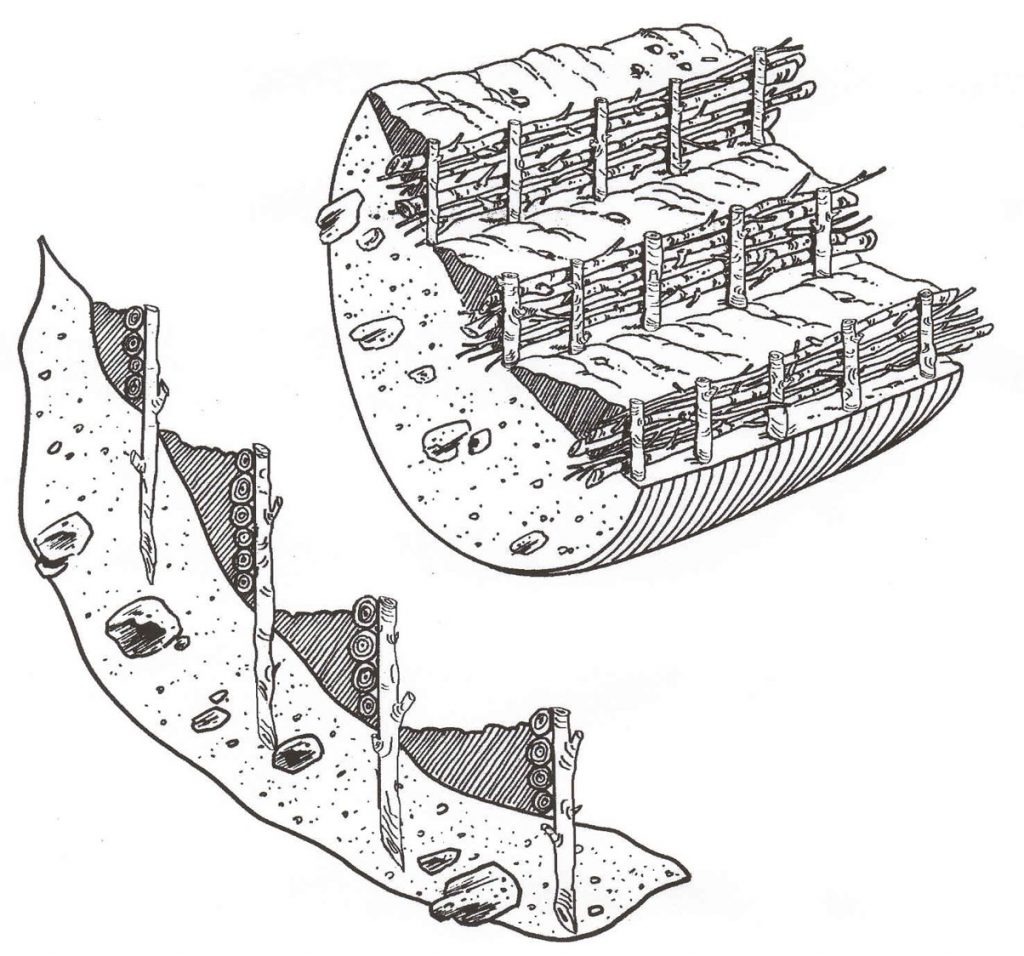

The type of access trail or road used for exploration has an impact on reclamation requirements. In keeping with the mitigation hierarchy, projects should be designed whenever possible to limit the length and width of access roads and the depth of cut into soil.

Notice of Work permits and the reclamation bond calculator recognize three different types of access roads that you should be familiar with: exploration trail, excavated trail and temporary access road. The table below provides details for each of these types of access features.

Types of Exploration Access*

| Exploration Trail | Excavated Trail | Temporary Access Road | |

|---|---|---|---|

Photo: AME |  Photo: Kirsten MacKenzie/AME |  Photo: Gary Wesa/AME | |

| Purpose | Minimal-impact access for movement of mechanical equipment, typically small drilling rigs, which do not require a wide route clearance. Includes corduroy trails. | More substantial access route designed for movement of equipment typically used in advanced exploration but excludes use of trucks for hauling mined material. Does not provide for a running surface for regular haulage. | Provides for access to and on mineral and coal tenures by mechanized equipment, including haulage trucks; designed and built to higher standards than those required for an excavated trail. |

| Width (into mineral soil) | 1.5 m excavated mineral soil | Up to 3.5 m excavated mineral soil; may be wider if cut and fill is used or only a shallow cut is required. | Professional design |

| Depth of cut | less than 30 cm into mineral soil | Greater than 30 cm into mineral soil | Professional design |

| Drainage | No ditching needed; water bars and outsloping surfaces adequate to handle expected flows. | Drainage ditches required to control movement of water. | Ditches, bridges and culverts must be designed to handle expected water flows. |

| NoW requirements | Locations of stream crossings and topographic features that influence the selection of a route must be noted on Schedule A map. | Show route on Schedule A map; information on impacts on timber; streams; wetlands and lakes; fish wildlife and their habitats; and mitigation. | Survey, layout, design criteria, drainage, impacts on other resource values, management of sediment and unstable materials from road construction, terrain stability. |

| Terrain stability | Not permitted in areas with terrain stability Class V, or in community watersheds classified as Class IV or V, unless a qualified person determines that area is not Class IV or V, or that trail or road would not cause terrain to become unstable. | Not permitted in areas with terrain stability Class V, or in community watersheds classified as Class IV or V, unless a qualified person determines that area is not Class IV or V, or that trail or road would not cause terrain to become unstable. | |

| Maintenance | Must be maintained while in use. | Inspection schedule and remedies for road or drainage failures required. May be used for several field seasons. | |

| Reclamation | Removal of bridges and stream culverts, restoration of channel and bank stability, and revegetation of exposed mineral soil required. | Same as those for Exploration Trail but must account for terrain stability and water quality. | Permanent reclamation required when road is no longer required or has not been used for more than 3 years. |

| Tenure off claims/leases | Application or Exemption for Special Use Permit under the Forest and Range Act. | Application or Exemption for Special Use Permit under the Forest and Range Act. | Application for Special Use Permit under the Forest and Range Act. |

* From the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in BC

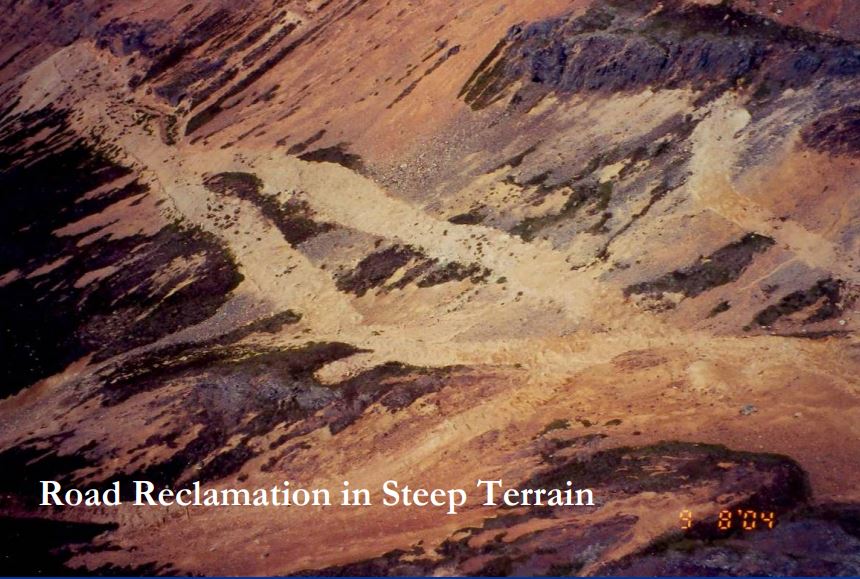

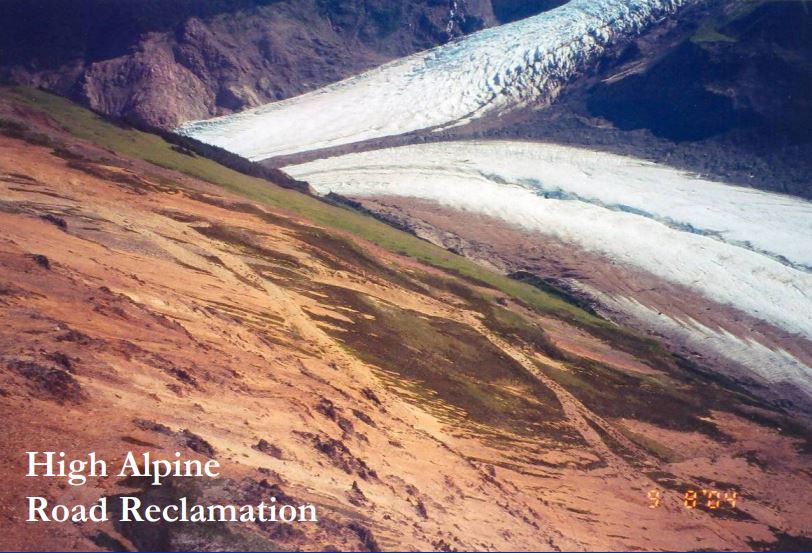

Terrain and Slope Stability

Terrain assessment data can be used to inform a project’s bond calculation as exploration trails, excavated trails and access roads are determined, at least in part, by slope steepness or terrain ruggedness. Trails and roads built on slopes greater than 30% are bonded at a much higher rate than those built on slopes less than 30%, as reclamation considerations and costs differ substantially (see the bond calculator). The 30% slope threshold is used to determine the type of road or trail required; an exploration trail is a bladed trail on slopes less than 30%, whereas an excavated trail is a cut and fill trail on slopes greater than 30% (a bladed trail is no longer acceptable). Terrain assessments may also include information regarding the terrain class (e.g., I, II, III, IV, V). This information is useful in planning and bonding for reclamation as slopes that fall within terrain classes IV and V are difficult to build on safely and reclaim successfully. Typically, an engineer is required to provide input on construction within these areas.

- Safe and stable road construction and reclamation for any roads with a slope greater than 20% (terrain class II and higher) can be challenging and should involve consultation with and/or design by an appropriately qualified professional.

Publicly available online resources that provide slope steepness/terrain ruggedness data are difficult to access and may need to be provided by a proponent’s local EMPR office or through a survey on site. The provincial iMapBC application contains data layers with terrain mapping information; however, the terrain stability information is often missing. Coarse-scale slope information (e.g., maximum, average and minimum slope percentages) can be gleaned from the Soil Survey Polygons layer when loaded into iMapBC.

Terrain Stability Classification*

| Terrain Class | Slope Class | Features | MX Program Specifics | Survey Mine Plan Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 0 –20% |

|

|

|

| II | 20 – 40% |

|

|

|

| II to III | 40 – 60% |

|

|

|

| IV | 60 – 70% |

|

|

|

| V | 70% |

|

|

* From the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in BC

Stream Crossings

Locating all stream crossings within a project area can be done through the province’s iMapBC application. However, it is considered good due diligence for a proponent to physically inspect their project area when assessing stream crossings and to have a qualified professional assess each crossing for the presence/absence of fish. The definitions section of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia provides a definition of a Qualified Professional. When planning a stream crossing, it is critical that a proponent understand the requirements of working in riparian areas specified in section 9.5.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia and how fish bearing and non-fish bearing streams are managed accordingly (see also section 4 of the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in BC). The Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia and the Water Sustainability Act (WSA) apply to fish-bearing stream crossings when planning for the installation or reclamation of structures. The Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia requires that all stream crossings (fish-bearing or not) are reclaimed in such a way that restores drainage patterns, supports stabilized banks with minimal erosion, and supports the establishment of self-sustaining vegetation that is appropriate for the site following the removal of the crossing structure (e.g. culvert, bridge).

Section 10.4.5 from the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in BC contains key information related to stream crossing and should be consulted, at a minimum, if new exploration access trails or roads require a stream crossing. The BC Government’s Engineering Manual for resource roads provides good information on road construction and deactivation, including stream crossings.

Stream crossings, even temporary ones, can affect fish by blocking fish migration routes, impacting in-stream or riparian habitat and silting downstream channels. This includes small channels that provide access to fishery-sensitive zones such as small side channels or wetlands. As such, fish-stream crossing structures should retain pre-installation stream conditions as much as possible. The objective is to ensure that the crossing permits peak flows but does not restrict the stream channel width or change the stream gradient, and that the natural streambed characteristics are retained or replicated.

Minimum Design Peak Flows for Bridges and Culverts*

| Crossing Type | Return Period (Years) |

|---|---|

| Permanent Bridge | 100 |

| Temporary Bridge | 50 |

| All Stream Culverts | 200 |

From the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in BC

While the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia specifies that stream culverts are required to be sized for a 100-year return period (section 9.10.1), the Water Sustainability Regulation (section 39(1)(vii); BC Reg. 278/2019) specifies a 1 in 200-year maximum daily flow. This is the value that many inspectors default to for culverts.

Planning Drill Pads and Sites

While the location of drill holes is primarily dictated by geology, drilling infrastructure should, where possible, avoid unstable slopes, overly steep terrain, areas of saturated soils, streams or riparian setbacks (as specified in section 9.5.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia) unless a management plan has been approved by an inspector. Use of existing clearings should be considered whenever possible and the location of drill sites should be chosen to minimize the overall disturbance including the construction of access roads.

- The reclamation bond calculator uses two different terms for drilling infrastructure, depending on the exploration activities. The term drill sites used for ground-based exploration, whereas the term drill pads is used for helicopter-based exploration. Both are bonded at different prices, and are based on size (small [10 x 10 m] or large). Details regarding what constitutes a small or large drill pad or drill site are provided in the Regional Mines Reclamation Bond Calculator Guidance Document.

Planning Trenches

Trenches, used to establish the surface trend and other key characteristics of a mineralized zone, are bonded for reclamation based on volume (m3), calculated from length, width and depth specifications. Further information can be found in the Regional Mine Reclamation Bond Calculator Guidance Document.

- To facilitate reclamation following exploration activities, trenches should be built in such a way that separates and stockpiles woody debris, topsoil materials (e.g. overburden) and subsurface materials (e.g. rock) from each other. Similar site-specific reclamation requirements of trails and roads will apply to trenches.

- Planning and sequencing of trenching should be done to allow for progressive reclamation, when possible. Consider the cost of equipment mobilization, personnel and ferry time back to the project area against the benefits of keeping the trenches open after field mapping, data collection and lab assays results are received.

Regulatory Requirements For Reclamation in BC

Reclamation Requirements in the Health, Safety and Reclamation code For Mines in British Columbia

The Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia outlines the requirements for reclamation of exploration projects. Guidance and information regarding reclamation liabilities are described in Part 9 of the Code.

- The Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia is the primary document for regulating the Province’s mining industry. It includes regulatory standards that address all stages of a mine’s life cycle, from exploration through to mine development and closure and reclamation. Information on reclamation liabilities, permitting and reclamation can be found in sections 9.10.1 and 9.13.1 of the Code.

Explorers should take note of section 9.13.1 which states that “reclamation of mechanically distributed sites, campsites and exploration access shall occur within one year of cessation of exploration unless authorized in writing by an inspector”. Reclamation activities are not normally required to be carried out annually under multi-year and multi-year area based permits unless specified in the approved reclamation plan for a site or included as a permit condition. Following the five-year term of these permits, reclamation of all disturbance features is required within one year according to the reclamation plan submitted as part of the Notice of Work permit application.

Notice of Work Permit and Annual Reports

Mineral exploration proponents are required to submit a Reclamation Plan as part of Notice of Work permitting. The plan should contain conceptual reclamation details of all aspects of the exploration activities, including proposed use and capacity objectives for land and watercourses, and an estimation of the total expected costs of outstanding reclamation obligations using the reclamation bond calculator. The purpose of this requirement is to ensure that an acceptable reclamation plan is in place and that funds are available to realize the reclamation and mitigation plans if the proponent defaults on their requirement to complete the reclamation work.

- Once permits are obtained, mineral exploration projects are required to submit an annual summary of exploration activities to maintain compliance with their permit and with the requirements of the Mines Act and section 9.2.1(3) of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia.

The annual summary outlines the work that was completed, the nature and extent of any disturbances and the areas that have been reclaimed. Please note that all mineral exploration projects are required to complete the Annual Summary of Exploration Activities. If work was completed under a Multi-Year Area Based (MYAB) permit, proponents must also complete the Multi-Year Area Based Work Program Annual Update. Mineral exploration projects are not required to fill out the Annual Reclamation Report unless otherwise stated in permit conditions. This report is required for current or past operating mines.

BC Reclamation Bond Calculator

Reclamation bonding is a requirement of Notice of Work permitting in BC. In 2018, the BC Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources released a bond calculator that should be used by all exploration projects to estimate the cost of reclamation. The bond calculator applies standard rates for a suite of common reclamation activities associated with mineral exploration activities as well as for placer mines and sand and gravel quarries. The tool was designed for ease of use, versatility and accuracy to provide a reasonable estimate of anticipated reclamation costs. It also provides inspectors with a fair and consistent means of assessing a project’s reclamation liability. Please note that the bond calculator is based on the premise that a third-party contractor will need to undertake the reclamation work, as that would be the case if a company defaulted on its obligation to undertake the exploration work.

- The bond calculator can be downloaded online as a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet so that proponents can document and adjust their reclamation estimations as necessary, or run several different scenarios (e.g., road access or helicopter access) to compare estimated costs. The calculator has been developed in accordance with the reclamation requirements specified in the Mines Act and the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia. There is also a useful guidance document that should be used in conjunction with the calculator.

When reclamation has been completed and all requirements have been met, the owner, agent or manager can apply for the reclamation bond to be returned. The application for bond return should be submitted together with a summary of the reclamation process, including photographs documenting site conditions at both the initial and end stage of reclamation (see Documenting Reclamation Activities). More details about reclamation bonds and their return can be found here.

Carrying Out Exploration

Preservation of Soil, Timber and Coarse Woody Debris During Exploration

Reclamation of disturbed exploration sites is greatly assisted by using soil and woody material that was removed and stockpiled from the site during exploration. These materials contain organic material, seeds, living plants and roots that will aid with revegetation and can generate a variety of habitats, reduce soil erosion, increase slope stability and prevent unwanted access to reclaimed sites.

Soil salvage planning in the initial exploration planning phase will ensure that exploration activities result in the effective stripping of topsoil materials that will then be available for use in rough and loose surface preparation during reclamation. The preservation of coarse woody debris during soil salvage is another planning consideration that will also vastly improve the reclamation of a site. Each of these considerations will result in better slope stability and long-term erosion and sediment control. Even in areas with limited soil development, the top layer of overburden should be separated from underlying material as it will likely still contain seeds, roots and organic material that will help with revegetation of the site.

- Soil, woody debris and trees that are removed to facilitate exploration must be preserved and used in the reclamation of the disturbed sites.

Likewise, trees that are felled for construction of access roads, trenches, drill sites or camps should be preserved for reclamation. In general, felling of trees should be kept to a minimum taking no more than necessary for safe working conditions. Felled trees should be bucked and limbed in preparation for reclamation work. If they are not to be used to support reclamation of the site, they should be laid in close contact with the ground to promote decomposition.

Coarse woody debris refers to fallen dead trees; these include sound and rotting logs and uprooted stumps. The logs and stumps can be in various stages of decomposition, located above the soil. To separate coarse woody debris from fine woody debris, a minimum diameter of 10 cm can be used but may vary depending on the exploration location. The collection and stockpiling of soils for reclamation should include roots, small woody debris and plant fragments. In some cases, plant roots, living plant fragments and seeds contained in the soil will regenerate and assist with revegetation once the soil is applied to the reclamation site. Stumps and other small woody debris included with the salvaged soil will also create substrate diversity and contribute organic matter. This, in turn, encourages the maintenance of biological diversity in the salvaged soils.

The Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia specifies that exploration activities must be carried out in a manner that minimizes soil losses so that a site can be reasonably reclaimed to support appropriate self-sustaining vegetation. Smooth, uniform slopes that are seeded with agronomic species are generally no longer acceptable from a reclamation perspective. Rough and loose surface preparation with the incorporation of course woody debris is not only important from a soil standpoint, but also provides wildlife habitat benefits and may discourage off-road vehicle use of reclaimed linear features and drill pads.

When large areas of soil are to be disturbed, you should plan how soils are going to be stripped, stockpiled and subsequently used in site reclamation prior to any work on the site to avoid the need to move stockpiles and the risk of mixing topsoil and rock materials and contaminating stockpiles with soil fines, drill fluids, fuels and oils.

- Where practicable, consider removing soil from one area and reapplying it to another site immediately to limit the need to stockpile soils.

- Where stockpiling of salvaged soils is unavoidable, stockpiles should be located in a convenient spot easily accessible for reclamation. Stockpiles should be signed or marked so they are not inadvertently contaminated or buried beneath other material.

- The surface area of stockpiles should be maximized to maintain higher levels of biological activity. Build a windrow of salvaged soils around the edge of the exploration site that will serve as a barrier to runoff and as a convenient configuration for storage of soil materials.

- Temporary vegetation covers could be used on soil stockpiles that are going to be in place for two or more months in order to stabilize the stockpile, limit erosion and limit establishment of invasive species. The use of annual rye and perennial native species will ensure rapid establishment of ground cover without the long-term impacts of a dense agricultural grass and legume cover, which are known to prevent the re-establishment of natural local native plant species. Seeding will be applied at a density prescribed by the supplier.

- Reasonable precautions should be taken to minimize the potential for soil stockpiles to become sites of invasive plant infestation, as any invasive plants on stockpiles may then be spread on the reclamation site.

Excavators rather than bulldozers should be used for roadbuilding where practicable. This will allow selective stripping of surface soils and placement of material in a location where it will be available for reclamation once use of the road is complete. When reclaiming a trail, road, drill pad or drill site, removing compaction from the surface is critical to promoting the re-establishment of vegetation; and thus, the development of a desired end land use and the reinstatement of pre-development land capability. Decompaction of a surface is accomplished using a dozer equipped with appropriate ripper, shanks or subsoilers. Natural Resources Canada has created a useful guide to soil salvage that is worth reviewing.

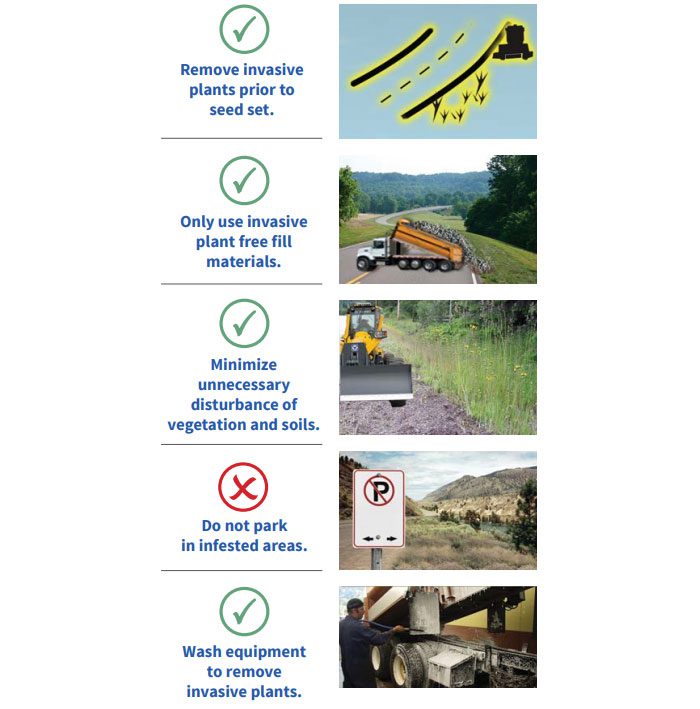

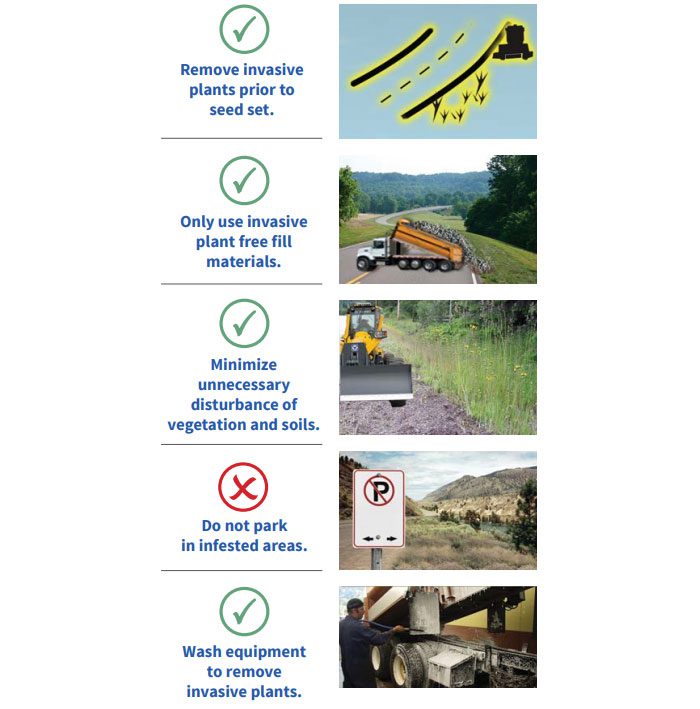

Invasive Species Prevention During Exploration

Mineral exploration projects should take proactive measures to avoid bringing invasive species onto the project site and to limit the spread of invasive species that are already on the site.

Invasive plant species exist throughout BC and have economic, environmental and social impacts on the province. Invasive species reduce soil productivity and water quality, degrade range land and wildlife habitat, impact forest operations and decrease the recreational value of land. Annual crop losses in BC due to invasive plants are estimated at $50 million (Invasive Species Council of BC). Without natural enemies to control their populations, these weeds have a competitive advantage over local native plants that makes them very difficult to control.

Section 9.13.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia requires that appropriate measures be taken to minimize the establishment of noxious weeds. The Invasive Species Council of BC (ISC) has additional information on species identification and acceptable control measures for species of concern within each region. Although ISC does not have a publication specific to mineral exploration, a guide for oil and gas workers has valuable information that applies to mineral exploration sites along with a guide to managing invasive species along roadways.

Mineral explorers should take the following steps to minimize the impact of invasive species within their project area:

- Clean all vehicles, equipment and gear with water before coming onto site.

- Minimize soil disturbance that can become the site for invasive plants.

- Reclaim disturbed sites as soon as possible to prevent invasive species from becoming established.

- Stockpile soil and coarse woody debris that contain native seed stock, roots and plan material so native plants can re-establish quickly on reclaimed areas.

- Remove invasive species from stockpiled soil prior to placing on reclamation sites.

- Earth moving equipment should be used in un-infested sites before infested sites to prevent the spread of invasive weed seeds and other plant parts.

Drill Pads and Sites During Exploration

To facilitate reclamation following exploration activities, drill pads and sites should be built in such a way that minimizes disturbance and that separates and stockpiles woody debris and topsoil materials (e.g., overburden). Similar site-specific reclamation requirements of trails and roads will apply to drill pads and sites.

The following measure should be implemented when developing drill pads and sites in order to facilitate reclamation of these sites after drilling is completed.

- Create the smallest practicable drill pad area consistent with safe working practices.

- Tree cutting should be minimized – only clear and area as large as necessary for access and safety.

- If stripping or levelling a drill site is required for safe location of a drill pad, topsoil and overburden should be removed as required and saved separately, nearby in low mounds or windrows. It should be returned as soon as practicable in the reverse order to its excavation.

- Topsoil and overburden should be stored on the upslope side of the drill pad when safe and practicable to do so to minimize risk of erosion.

- Drill holes that release artesian waters to the surface can cause ground saturation and subsequent slope failure. These holes should be adequately sealed wherever the release of artesian water creates a risk. The Regional Mines Reclamation Bond Calculator includes a provision for the cost of sealing drill holes. During permitting, mines inspectors may include the cost of sealing a select number of drill holes, in anticipation that some will need to be sealed due to artesian waters.

- Oil-absorbent matting should be on-site and available to be used to catch grease and oil around the drill rig.

- Design of surface drainage structures should be based on the expected flow, subgrade soil conditions and the expected duration of their use. Ditches should be constructed on the upslope side of the drill pad, and a sump should be built on the downslope side of the pad. Surface drainage structures (e.g. interceptor ditches) should be constructed to intercept and divert runoff, preventing erosion of the drill pad and sump.

Developing Sumps

Drill fluids, additives and cuttings that have the potential to harm aquatic species and habitat should not be released into waterways or allowed to run uncontrolled. An adequate closed-circuit recirculation facility should be provided for drilling mud and flocculating agents. Acceptable collection techniques include dug sumps, tanks and well-constructed, impervious, walled settling ponds a short distance downslope from the drill.

Construction of sumps should be on the downslope side of the drill and follow similar approaches to constructing trenches. That is, remove soil or growth material first and separate to one side of the sump. Overburden (gravel or rock material) should be placed on another side or around the sump.

Reclamation of a sump should be carried out as soon as the mud has settled and consolidated to allow proper backfilling without displacing the mud out of the sump and causing uncontrolled release. Overburden, then soil and woody debris can be put back into the sump after drilling to bury the cuttings and drill mud. The drill mud should not contain materials harmful to plants or groundwater if buried in place.

Access Trails and Roads During Exploration

A wide network of roads and trails built to facilitate resource development, forest management and fire suppression exists in most areas of BC. As such, the construction of new road access may not be required in the initial stages of exploration. However, short extensions from existing roads may be desirable for reasons of safety and practicality. In order to drill or trench in later phases of exploration, a proponent must have the ability to move equipment to and around the target area in a safe manner. In many cases, this is done by air, particularly when the test program is small, and the site is remote or in mountainous terrain. In other cases, ground access is preferred, particularly where the target area is near existing roads or trails.

A proponent will be required to provide information about the type of access being proposed, its routing, inspection and maintenance in addition to identifying stream crossings and the installation of bridges and/or culverts through the Notice of Work application process. In general, access design should plan to create the minimum permanent road length practicable through the use of existing main access roads and secondary tote roads. Existing trails and roads should be used whenever practicable. In addition, planning and construction should aim to create the narrowest access practicable, consistent with safety and traffic needs. This will avoid unnecessary disturbance, as well as costs in design, approvals, construction and reclamation. In some locations drilling during the winter is possible and has the advantage of limiting the impact on soil and vegetation.

Road Clearing

Section 9.10.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia specifies that clearing of standing timber shall not exceed the minimum required to accommodate the road prism, user safety or other operational requirements. Where practicable, slash from the road right of way may be windrowed along the toe of a fill slope to assist in runoff filtering. In all cases, timber and other vegetation should be retained (piled, windrowed) for reclamation.

Drainage and Erosion Control

Minimizing the disturbance footprint is one of the most effective (and economic) ways to prevent erosion and reduce runoff. Working in winter is another option that reduces damage to the natural soil surface; however, not always practicable. Erosion should be considered in determining the timing of exploration activities; when moving and/or removing soil materials, work should be conducted during dry weather. Also, exploration work should be scheduled so that work in one area is completed and disturbed sites restored (if no longer needed) prior to moving to the next area.

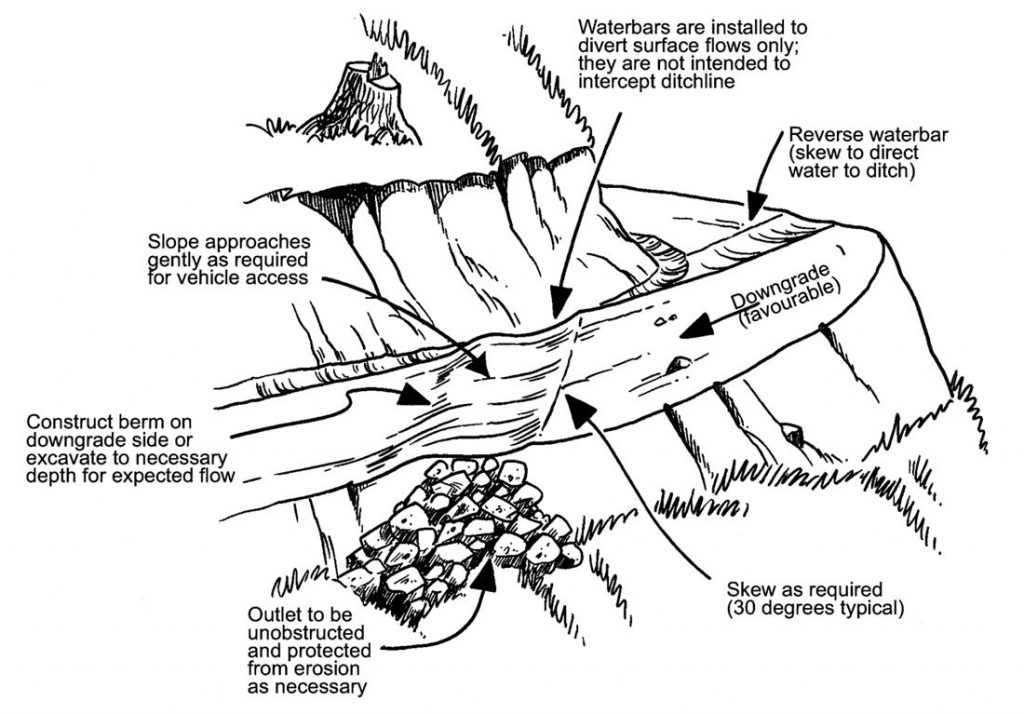

Disturbed soil from the development of access trails or roads should be stored on the upslope side whenever possible to minimize risk of erosion. Creating a rough uneven surface will help control sheet erosion by slowing runoff and encouraging infiltration.

Access trails and roads require careful planning to ensure effective drainage. Drainage structures for excavated trails should include a system of dips and water bars placed sufficiently close together so that the runoff can be dispersed. Water bars should be slanted across the road prism to drain water downhill and should be reinstalled and maintained each field season.

Spacing of Water Bars*

| Slope Gradient | Erodible Soils (silts and clays) | Normal Soils (loams) | Rocky Soils (sand and gravel) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 5% (3°) | 45 m | 60 m | Nil |

| 5-10% (3-6°) | 35 m | 45 m | 60 m |

| Over 10% (6°) | 15 m | 30 m | 45 m |

Temporary access roads require ditches and culverts capable of withstanding a 100-year return flood flow. Surfaces should be crowned so that water flows into the ditches toward culverts. Culverts should be slanted across the road at a minimum 1% downslope gradient and should spill onto stable slopes. Erosion controls (e.g. rocks, half culvert downspout) should be installed to dissipate energy from flowing water. Culverts should be marked and maintained.

Section 9.10.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia also states that there shall be a program to routinely monitor and maintain exploration access as necessary and prudent so that it is stable and safe for the intended use until it is reclaimed to the satisfaction of an inspector.

For additional information proponents should consult the BC Government’s Engineering Manual for resource roads.

Roads and Trails on Steep Slopes

Roads and trails should fit the topography of a site, using natural benches, ridgetops and flatter slopes to avoid excessive cuts and fills. Not only will this practice reduce construction costs, but it will avoid the possibility of unstable cut or fill slopes. In general, roads should be designed to keep grades as low as possible.

- If you propose to build or upgrade access roads or trails in steep and/or unstable areas, you should engage the services of a qualified professional engineer to design and oversee road construction.

Some Approximations Regarding Slopes*

| Feature | Percent | Degrees | Horizontal : vertical |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum for main haulage | 8 | 5 | 11:1 |

| Short pitches | 10 | 6 | 10:1 |

| Approximate two-wheel drive maximum | 15 | 9 | 6:1 |

| Maximum soil slope for vegetation | 50 | 26 | 2:1 |

| Angle of repose earth fill | 67 | 34 | 1.5:1 |

| Angle of repose angular rock | 80 | 39 | 1.25:1 |

*From the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in BC

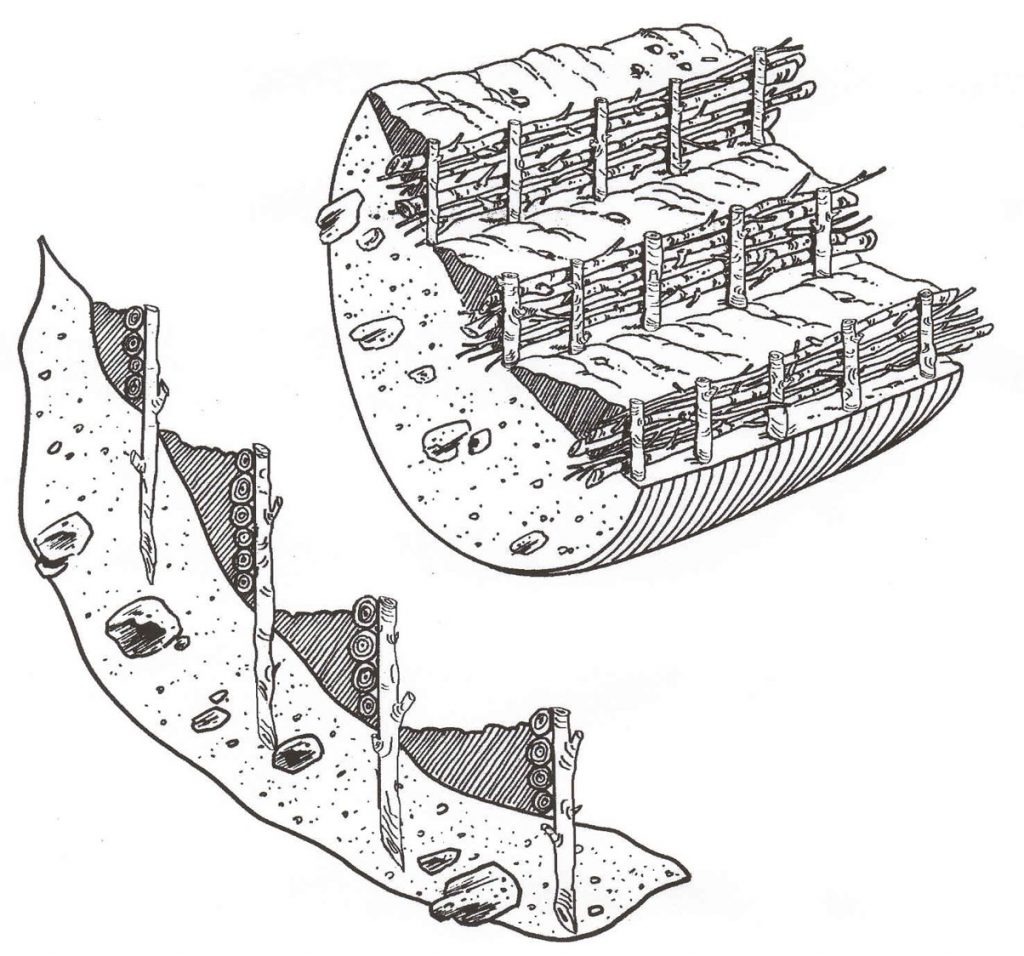

Trenches During Exploration

Trenches should be designed and built to minimize disturbance, ensure stability and allow for safe working conditions as specified in the Code. Material excavated out of a trench should be separated (soil and overburden) and stored in a stable location until it is used for reclamation.

Topsoil, subsurface material or other excavation spoils should be placed safely near the excavation. Losing the material downslope of a trench or pit may make recovery for reclamation difficult. Where the slope is not an issue, topsoil should be selectively placed to one side and overburden (subsurface material) to the other, so that the trench can be refilled in reverse once sampling has been completed. The potential for ML/ARD should be assessed to ensure materials with the potential to leach metals or generate acid rock drainage, which are exposed during excavation, are managed appropriately. For trenches where the volume of rock is small and will be exposed for a short period of time (one season or less) potentially acid generating rock can be separated and placed at the bottom of the trench when backfilling it for reclamation. If a large volume of rock is being removed and will remain exposed for several seasons, a more active management plan may be needed for potentially acid generating rocks. Please discuss this with a mines inspector and consult the BC Metal leaching and Acid Rock Drainage policy and guidelines.

On steep slopes where the trench may be in use for an extended period (more than one month), topsoil and overburden may need to be removed from the site and stockpiled separately in a safe, flatter location. In some cases, the material should be placed at the ends of the excavation or removed and stockpiled. Topsoil and overburden piles should be covered during wet seasons or weather to reduce the risk of soil erosion.

Although not specified in section 9.10.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia as with roads, the clearing of standing timber should not exceed the minimum required to accommodate the trench dimensions, user safety or other operational requirements. Slash from the trench clearing should be windrowed or stockpiled for reclamation. Consider the use of utility vehicles with backhoe attachments in trenching operations to limit the need for road construction. Where practicable, trenches should be oriented to follow the contour of the slope on slopes greater than 26° (2 h:1 v). This reduces erosion exposure and allows excavated material to be more easily deposited to one side of the trench.

Health and Safety Requirements for Trenches

Section 9.3.3 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia specifies the design and working conditions of trenches to ensure safety and stability of the trench:

- Trench width: When it is necessary for persons to enter a trench, the excavation shall be wide enough to allow a person to turn around without contacting the sides of the trench.

- Trench shoring: No person is permitted to enter any excavation over 1.2 m in depth unless the sides are sloped to a safe angle down to 1.2 m or the sides are supported according to specifications of part 4 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia. Section 4.17 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia specifies what type of lumber can be used for shoring; the use of steel and hydraulic pneumatic jacks; and how shoring should be installed.

- Trench sloping: The sides of excavations may be sloped instead of shored, depending on soil or rock conditions, as long as stable excavations can be maintained. Slopes must not be steeper than 1 (horizontal) : 1 (vertical).

- Working in excavations: Excavated material shall be kept back a minimum distance of 1 m from the edge of any trench and 1.5 m from any other type of excavation. An excavation shall be inspected by a qualified person before anyone is allowed to work in it. A ladder must be kept near anyone working in any excavation over 1.2 m deep. Excavations must be covered or guardrails installed where there is danger of people falling into them.

Reclamation of Drill Pads and Sites

The reclamation of drill pads and sites should include the sequential replacement (i.e. subsoil or rock first, topsoil or overburden last) of stockpiled topsoil and overburden in such a way that the goals of rough and loose surface prep are achieved. Timber and other vegetation that was stockpiled/windrowed during drill pad/site construction should be placed among the rough and loose soil topography. Section 9.13.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia requires that all mechanically disturbed sites (including drill pads and sites) are reclaimed within one year of cessation of exploration unless otherwise authorized in writing by an inspector.

Other tips for reclaiming drill pads and sites include:

- Sumps that have been constructed to collect drilling mud, rock fines or rock chips (from reverse circulation drilling) should be buried providing the drilling mud or rock material does not contain materials harmful to plants or groundwater.

- Drill pad surfaces should be ripped to reduce compaction and promote natural infiltration by rain and snowmelt.

- Safe discharge structures should be provided for seepage sites.

- High cut banks should be reduced to the extent practicable.

- Natural surface water flows should be restored to the extent practicable.

Reclamation of Trenches

The reclamation of trenches should include the sequential replacement (i.e. subsoil or rock first, topsoil or overburden last) of stockpiled topsoil and overburden in such a way that the goals of rough and loose surface prep are achieved. Timber and other vegetation that was stockpiled/windrowed during drill pad/site construction should be placed among the rough and loose soil topography.

Section 9.13.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia specifies that pits and trenches must be backfilled and reclaimed prior to abandonment, unless:

- The sides of the pit or trench are sloped to a stable and safe angle as determined by a qualified person, or the pit or trench is fenced to prevent inadvertent access, and

- There is a means for egress.

Management Practices for Different Ecosystems

Management strategies for reclamation should also be developed in consideration of site characteristics. Consideration of climatic characteristics and the type of native ecosystem expected at a site should be included in the reclamation planning process (e.g. drainage characteristics of wetland areas, ensuring adequate resloping of land to prevent soil erosion and the establishment of grasslands and brushlands on slopes) in addition to following stocking standards.

Consideration of Cumulative Effects

The province of BC is committed to measuring the environmental effects of all natural resource activities, large and small, on values that are important to the people of BC. Cumulative effects are changes to environmental, social and economic values caused by the combined effect of past, present and potential future human activities and natural processes. Laws, regulations and policies around natural resource management usually focus on a specific sector – such as mining. Formal environmental assessments consider cumulative effects when evaluating large projects; however, at this time, permitting for mineral exploration does not require such assessments.

BC’s evolving solution to assessing impacts associated with smaller projects is the cumulative effects framework. The cumulative effects framework is a set of policies, procedures and decision-support tools that help identify and manage cumulative effects consistently and transparently. The framework incorporates the combined effects of all activities and natural processes into decision-making to help avoid unintended consequences to identified economic, social and environmental values.

The cumulative effects framework does not create new legislative requirements; rather it informs and guides cumulative effects considerations through existing natural resource sector legislation, policies, programs and initiatives. Integrating the cumulative effects framework into existing natural resource decision-making processes and enabling cross-sector governance will ensure cumulative effects are identified, considered and managed consistently.

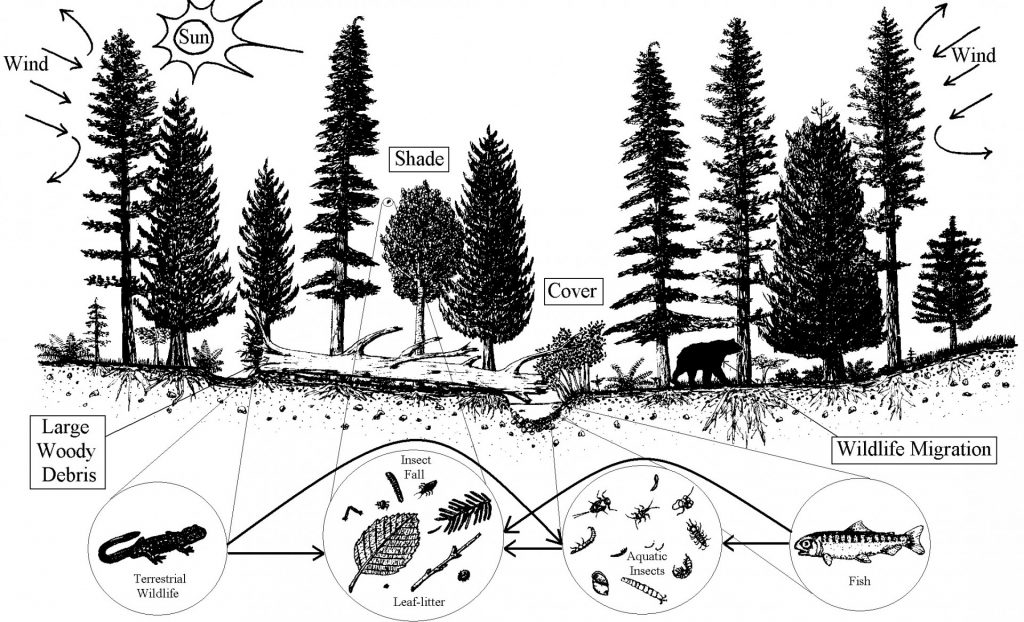

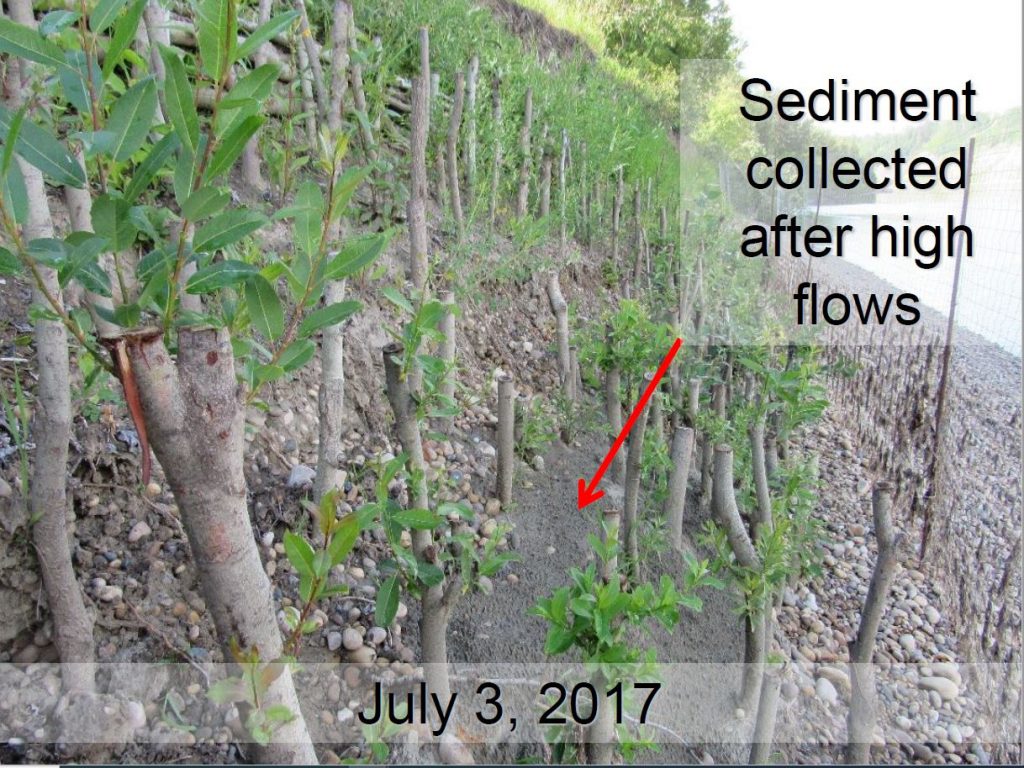

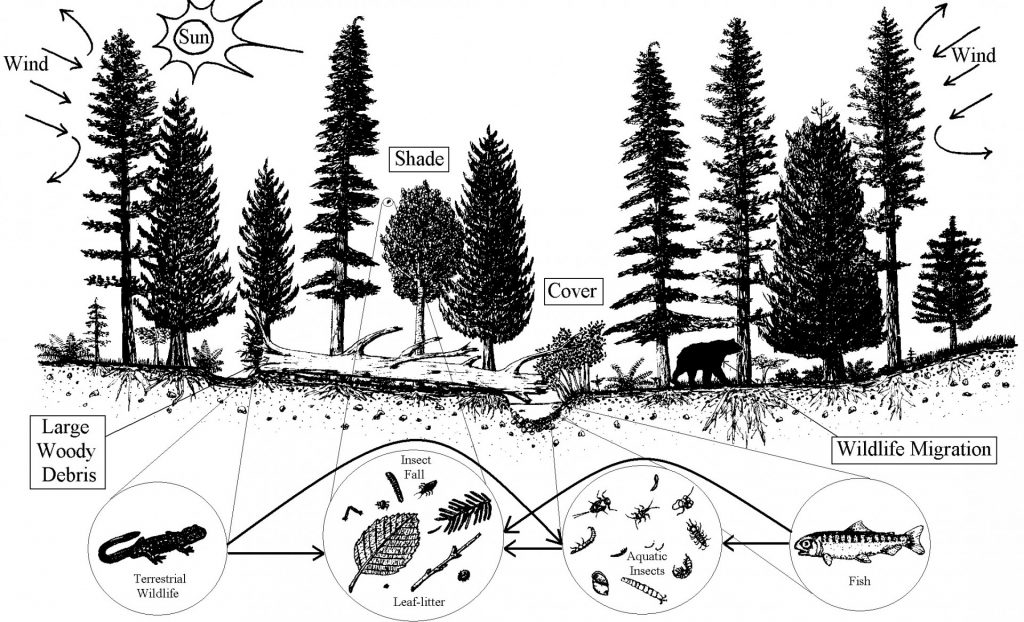

Management Practices for Riparian Areas

Riparian areas are the lands that occur adjacent to rivers lakes, and wetlands. They are distinctly different from surrounding areas because of unique soil and vegetation characteristics that are strongly influenced by the presence of water. Riparian areas comprise a very small percentage of the land base but are among the most productive and valuable natural resources.

In most cases mineral explorers should avoid work in riparian areas whenever possible. When work is planned in these areas, exploration-specific requirements for working in riparian areas should be reviewed. Part 9 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia and section 4 of the Handbook for Mineral and Coal Exploration in BC contain key information about riparian management.

Identifying the location, size and type of wetland or flood zone (including characterizing vegetation) are all important things to consider when planning and implementing wetland management to ensure thorough understanding of impacts associated with the exploration project. The province has developed a wetland and flood zone assessment handbook that should be used in the field to collect all relevant information about a wetland or riparian flood zone. The province has also developed a riparian classification standard that is used in the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia to determine setback distances, of which average stream size (in metres) is a determining factor (see Table 9.1 in the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia).

Riparian Setback Distances*

(measured horizontally from the top of bank)

| Riparian Type | Size | Drilling (m) | Exploration Access (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stream | Stream widths (m) >20 >5≤20 1.5≤5 <1.5 <0.5 in alpine areas above timberline | 50 30 20 5 5 | 70 50 40 30 15 |

| Wetland | Wetland Size (ha) >5 >1.0 <5.0 >0.25 <1.0 | 10 10 10 | 30 20 10 |

| Lake | – | 10 | 30 |

Scheduling exploration activities, including in riparian areas, should consider sensitive wildlife and aquatic life windows. For example, migratory bird nesting windows, and least-risk windows for fish species. In general, no ground-based machinery is to be fueled or serviced within a riparian setback area unless certain circumstances are met (see section 9.9.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia).