El Alacran gold mine is nestled in the jungle-covered hills of northern Colombia. The name means “the scorpion” in Spanish, and is a cluster of over 140 informal mining sites, intermingled with the homes of the 195 traditional mining families who operate them. For 40 years, these men, women and children have been extracting ore using rudimentary tools and equipment, just as some 16 million artisanal gold miners across South America, Africa and Asia do every day.

Not only is this backbreaking work for the miners, but the gold-extraction process harms the wider community and environment too. In the past, mercury-laden tailings from noisy ball mills have polluted the streams and creeks around the Alacran village. Schoolchildren walk home barefoot from the local school in these streams, and, until recently, village residents breathed in the toxic air produced from burning gold-mercury amalgam to retrieve the valuable gold.

But today, change is in the air, and not only because peace is slowly spreading across the country. Since 2011, Toronto-based junior Cordoba Minerals Corp. has been exploring the adjacent San Matias high-grade copper-gold project. In October 2015, together with joint-venture partner High Power Exploration Inc. (HPX), based in Vancouver, Cordoba acquired the right to explore the Alacran mine and surroundings – the final piece in a 260-square-kilometre land package. The social work, however, began back in 2011.

“Two years before geologists visited the site, Cordoba sent in a social team,” says Mario Stifano, CEO of Cordoba. “The area has incredible geological potential, but first we put our effort into building trust with the community, listening to their concerns and establishing a solid social licence to operate.”

Having built a strong relationship with the local villages, Cordoba was able to sign an agreement with the Alacran mining association relatively quickly in late 2015, and more than 100 former artisanal miners from Alacran were employed as field helpers and line cutters on the project during 2016.

“Everyone is working,” says Eliecer Velasquez, community leader and secretary of the Asociatión de Mineros del Alacrán. “We have worked this deposit for years, but under Cordoba we have secure jobs, better roads, and education programs for children and adults.”

Although the company is having a positive impact on the hundreds of people in this area, Cordoba’s leadership in this remote corner of Colombia puts only a tiny dent in a massive global problem. Over 30 million people worldwide are artisanal miners: half are gold miners, responsible for 12 to 15 per cent of the world’s gold supply, while others extract tin, tantalum, tungsten, diamonds and many other minerals. Poverty, conflict, brutal violence and environmental degradation go hand in hand with artisanal mining.

“Artisanal miners are living below the poverty line even though they’re sitting on millions of dollars’ worth of gold,” says Suzette McFaul, founder of SEF Canada Ltd., a Vancouver-based organization helping artisanal mining communities build the business skills they need to become safe, independent miners, or to diversify into other occupations.

SEF Canada launched the Clean Gold Community Solutions project in late 2016 to help artisanal miners and their communities become economically viable and environmentally safe in northern Ecuador. “There are miners and families who want to get out of mining but don’t have the tools, knowledge and opportunity to diversify or start to work in a different business,” explains McFaul.

National and regional governments need a helping hand, too. AME life member and past chair Rob Stevens recently joined the Canadian International Resources and Development Institute, a coalition of three Canadian universities working to improve resource governance and poverty alleviation around the world, with artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) as a key focus.

Traditional miner José Diaz continues to operate aging processing equipment at El Alacran mine

Local workers

Anderson and Carlos Mejía carry drill rods past El Alacran to Cordoba Minerals drill sites

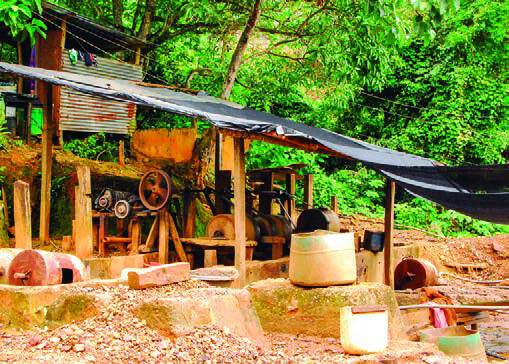

Rudimentary mining

and processing equipment

at El Alacran artisanal gold mining operations in northern Colombia

“The work that we do starts with a request from a national government who have identified an area where they need help to support the sustainable development of their natural resources,” says Stevens, explaining that governments need to understand the problem before they can develop useful policies to protect the environment and the people involved.

“Mining engineers in Canada learn a lot of high-end technical information about how to build and operate a major modern mine, and that’s important, but due to the type of mining, the ASM world requires a different technical skill set and an awareness of the complex social environment,” says Stevens.

Canadian geoscientists, engineers and other professionals are playing a key role in solving the global artisanal mining problem. Exploration companies – which have not traditionally invested in early-stage social programs and environmental monitoring – are realizing that solid community relationships and a wealth of baseline environmental data adds real value to an exploration project. A good first impression is invaluable, reduces the risk for potential investors down the line, and ensures new mines can be developed in socially and environmentally responsible ways that achieve prosperity for everyone.