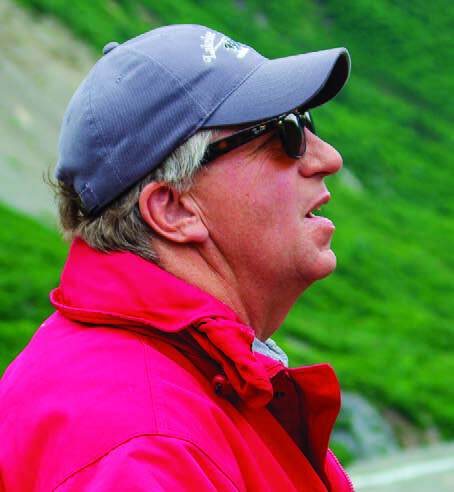

If finding a gold deposit is like finding a needle in a haystack, then starting the search at an old gold mine is like removing the hay from the equation. “A lot of mines have been found around other mines,” points out Bill Threlkeld. It was one of the reasons the exploration VP at Seabridge Gold Inc. pushed the Toronto-based company to acquire SnipGold Corp. and its Iskut property in 2016.

Mining dates back to the 1920s at the property north of Stewart in the Coast Range. And with 10 years of exploration work under his belt at Seabridge’s KSM property, just 30 kilometres away, Threlkeld knew the geology. After just one summer of exploration, the results suggest Seabridge is close to finding the needle at Iskut.

And Threlkeld realizes the more he looks at rocks, the more he sees the same things repeating themselves. “I’ve worked in Africa, Asia, the Andes and all over North America,” he says. “I’ve had the chance to see a whole lot of things, and certain setups will give the same thing no matter where you are on the planet. People told me that but I didn’t believe it until I saw it.”

Threlkeld’s initial attraction to geology was more vegetative than inspirational. At high school in Denver, Colorado, he took a general geology course. “The teacher would turn off the lights and show slides,” he remembers. “It was a lot better than anything else we were doing.”

Something resonated in that dark classroom. He enrolled in a geology program at Colorado State University, focusing on economic geology. He finished his degree at the end of the summer term and tumbled out of school with no job prospects. Out of the blue, a school friend called. His boss, Eliseo Gonzalez-Urien, needed a geologist at Noranda Inc.

“I’ve been working with Eliseo ever since,” Threlkeld says. “He’s the kind of guy that somehow gets you to put out more effort than you think you’re capable of. I fell in love with his love – finding things.”

After working with Noranda – mostly in Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and Idaho – Threlkeld was offered a chance to go to grad school at the University of Western Ontario. The company had a relationship with the school and Threlkeld took full advantage, expanding his understanding of exploration geology in general and the emerging epithermal gold niche. In the early ’80s, when Threlkeld was at Western, gold prices were too low for epithermal gold deposits to be economical. Threlkeld says one of the few people studying this type of deposit in the early 1980s was Bob Hodder, one of his professors at Western. “Bob had been working on them for seven or eight years at that point,” says Threlkeld.

Threlkeld moved on from Noranda to stints at Placer Dome Inc. and Greenstone Resources before eventually turning to consulting. With the industry in a downswing, it was not inspiring work. “Everyone was looking to fill holes in the dyke,” he says. “I wanted to build something.”

So when a former colleague at Greenstone called and invited him to join a team starting Seabridge Gold, Threlkeld didn’t hesitate. “They were looking to acquire properties while everyone else was getting rid of stuff,” he says.

Seabridge began building a portfolio of plays, all with previous exploration efforts. The plan was to do more ground work and then sell or partner with a company wanting to progress the project into a mine. Within the first three years, Seabridge bought nine properties worth $15 million. The work was different from what Threlkeld had done in the past – more data mining than prospecting.

“It’s exciting working where no one has ever looked before,” he says. “But the amount of time it takes to get a project built is frustrating. Working on a project where data already exists, you know what questions to ask before you get on the ground. You get to success sooner and you’re more likely to achieve financial success. That’s how everyone but geologists rate success.”

Seabridge didn’t acquire Iskut until the 2016 field season was already underway. Threlkeld began sifting through the property’s archives. It was the first time that data from the old mine and more recent exploration had been consolidated under one roof and examined with the experience that KSM granted the Seabridge team.

“We found a lot of the characteristics of the KSM property,” Threlkeld says.

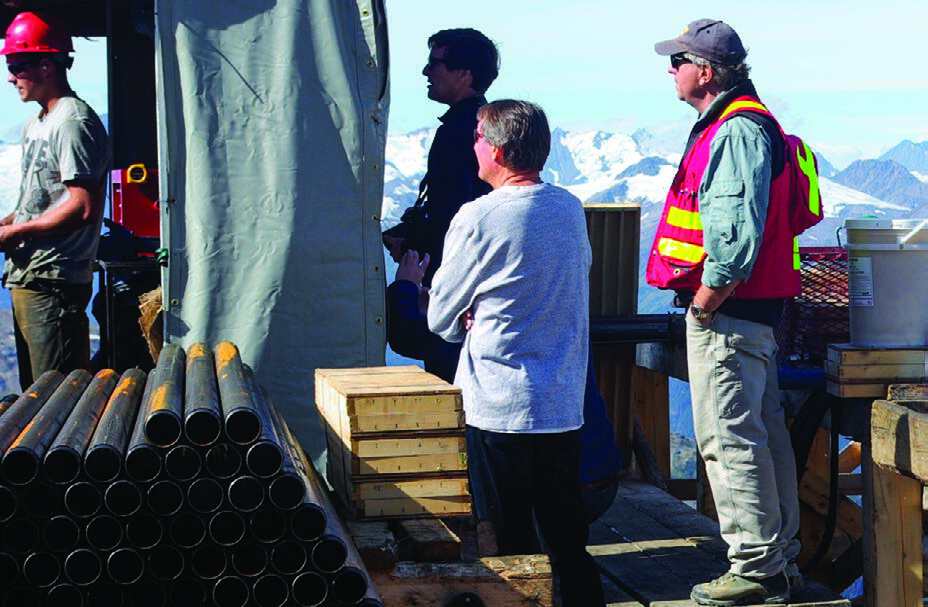

Then they started drilling and it looked even better. While KSM and other deposits in the area – Brucejack, KSP and Eskay Creek – are fractured deposits exposed by thrust faults, Seabridge’s early work suggested the Iskut deposit may be intact.

“We were surprised to find a cap over the porphyry system,” Threlkeld says. “It’s a quartz rise that looks like it belongs in Chile or southern Arizona.”

Planned exploration work for 2017 will drill into the cap to see if a hypothesis gleaned together from a 40-year career is correct. But the Iskut property is more than just a potential mine to Seabridge – it’s an opportunity to refresh the B.C. mining industry’s image.

The original Johnny Mountain Mine on the property represents the old, irresponsible days of mining, when companies walked away from properties without cleaning up first. Shaking that image is one of the biggest hurdles to building a mine at KSM.

“This is a different era. You can’t do things today that we would have done 30 or 40 years ago,” he says. “Nothing can demonstrate our intentions like action.”

Buying Iskut represents an opportunity to clean up Johnny Mountain, a goodwill move that Threlkeld hopes will convince opponents and skeptics of KSM that Seabridge isn’t just talking when it comes to its environmental commitments.

Iskut’s early success just adds to the excitement. Thelkeld says his work today is the highlight of his career. “We’re having fun, and what’s super exciting is the quality of the team,” he says. “It’s like working with a good group of friends who all happen to be really good geologists. I learn something new every day and it never feels like work.”