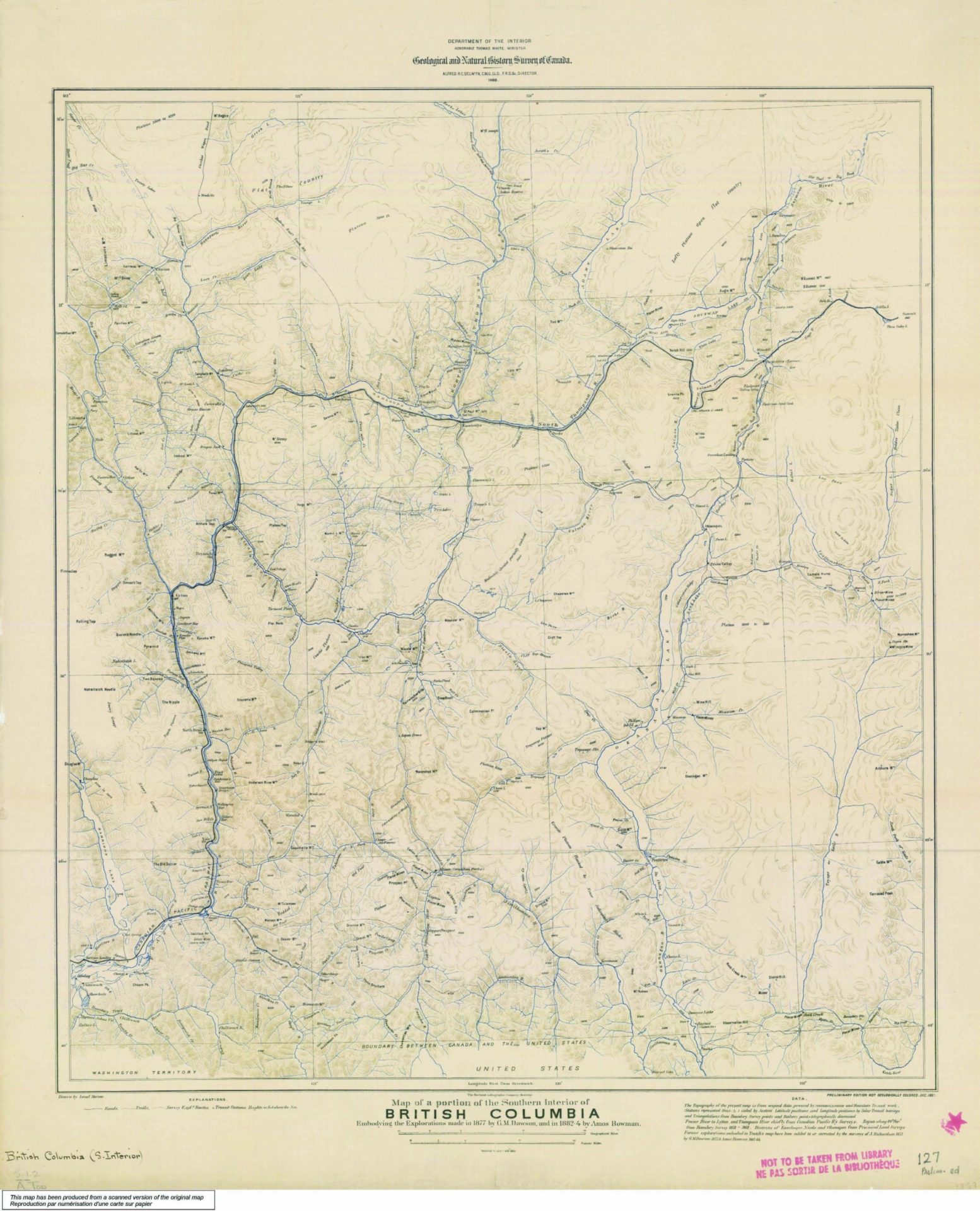

The first gold discovery in British Columbia was made in 1854 along the Pend d’Oreille River and its tributaries in an area southeast of Trail. Cries of “Gold!” echoed through the mountains, and soon hundreds of prospectors and placer miners were stampeding into southern B.C. in search of the next bonanza, some flocking from as far as Washington. Four years later, gold was discovered on the bars and benches along the Fraser River from Hope to Lillooet, and a year after that, prospectors and Chinese miners rushed to Boundary Creek near Greenwood.

In October 1859, Canadian prospector Adam Beame, on his way westward to prospect the Similkameen River near Princeton, camped on the banks of York Creek (soon after to be renamed Rock Creek) 36 kilometres west of Greenwood, at a location later to be called Soldiers’ Bar. Fortuitously, he scooped up a pan of gravel at this site to find coarse gold flakes lining his gold pan. Beame staked the first claim on Rock Creek and left the site with great expectations to return in the spring.

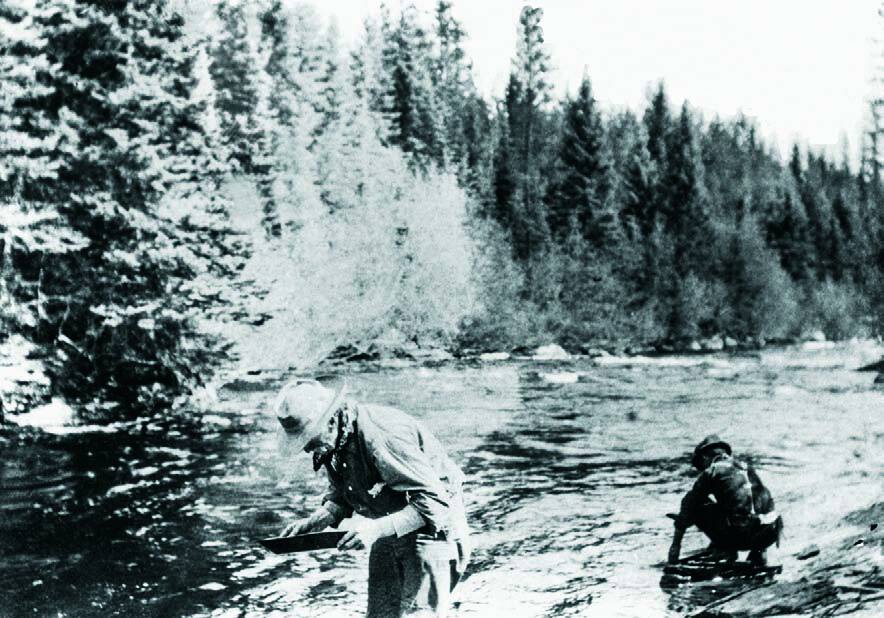

It was virtually impossible to keep the news of a gold discovery a secret, and by spring of 1860, hundreds of miners, many of them Chinese, swarmed northward from the U.S. and descended on Rock Creek. Beame returned on May 6, and in the first six weeks he recovered 60 ounces of gold with a rocker. By the end of July there were more than 300 miners spread along Rock Creek, where several bonanza bars and gulches were discovered along a 10-mile stretch.

Gold rush fever was heightened as daily reports flashed news of abundant coarse gold flakes the size of melon seeds, described as “gourd gold.” Many nuggets recovered from Rock Creek were over one ounce, the largest of which weighed in at a hefty 9.3 ounces. One of the richest claims was the Nolan, where three owners recovered 437 ounces to yield over $7,000 at a time when gold was $16 per ounce. There were many other claims on which the pay streaks of gravel produced between $2,000 and $5,000.

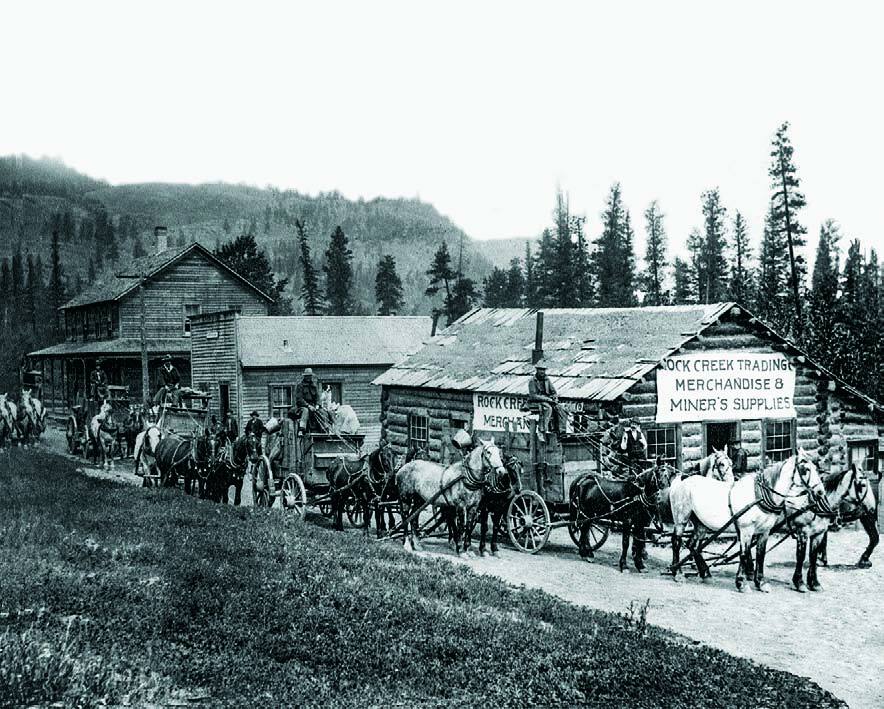

The boom town of Rock Creek sprang up on the banks of the creek in 1860. Initially, it consisted of a cluster of 12 log houses and shanties to accommodate two saloons, a liquor store, a butcher shop, five stores, a restaurant and one hotel. Most of the miners squatted along the creek on their own claims, and only came to town for supplies and maybe some frolicking. The migration of men to Rock Creek continued steadily through August, when about 150 hopefuls arrived from Oregon and as far away as San Francisco. To their disappointment, the best ground had all been staked and there was little for these late-comers to do other than odd jobs around town or working for wages at $4 per day for established claim holders.

Furthermore, all was not golden at Rock Creek as the huge influx of men created a serious shortage of supplies and groceries. These were being shipped in limited quantities by mule trains from the U.S. and Hope, a supply chain that became more reliable when wagon trains eventually replaced the mules.

Another issue was undesirable rowdies among the late arrivals who were causing mayhem, especially among the Chinese miners. Very quickly, the Governor of British Columbia, James Douglas, appointed Peter O’Reilly as gold commissioner with orders to restore peace at Rock Creek. But the lawlessness continued as O’Reilly was threatened and the trouble escalated into the “Rock Creek War.” Douglas returned in full uniform, confronted 300 miners and threatened to return with 500 marines if British law was not obeyed. The meeting ended peacefully, and the so called war was over.

James Douglas also noted that significant amounts of gold recovered by the miners were being sent back across the U.S. border or secreted away to bring back to China, and not benefiting the merchants of Rock Creek or New Westminster. Douglas recognized the need to have a reliable access route to the B.C. interior, and the Dewdney Trail was hastily constructed from Hope to Rock Creek, completed in 1861.

Meanwhile, the town of Rock Creek continued to prosper, adding a large billiards saloon, a government building and gambling houses. The town boasted a population of 350 – until winter arrived in November of 1860, sending many of the Americans south to Colville and Walla Walla for the season. Town activity came to a crawl as only a few miners, merchants and government officials remained until spring, when a number of claim owners returned to work on their claims.

Many Rock Creek miners did very well, earning as much as $120 per day with a rocker. Others, including Adam Beame, were attracted to new gold discoveries on nine creeks draining into Okanagan Lake near Kelowna. But as dramatically as it had begun, the Rock Creek gold rush ended in the fall of 1861, and by the following fall the settlement of Rock Creek was a collection of deserted buildings. In October 1866, a good part of the town of Rock Creek was destroyed by a fire, including the main store and a number of cabins.

Rock Creek was one of the richest gold creeks in B.C.: it was reported that well over $250,000 in placer gold was recovered in its heyday, when gold was $16 an ounce. The total number of ounces recovered will never be determined, as much of the gold was smuggled across the U.S. border or sent to China.

On the heels of the Rock Creek gold rush, prospectors combed the area searching for the possible source of the gold in the creeks. In 1884, the Victoria vein was discovered by two placer miners along upper Jolly Creek, a tributary of Rock Creek. There was no immediate followup work on this vein until 1887, when Al McKinney and Fred Rice discovered the Cariboo vein on the west bank of Rice Creek, about four miles north of Rock Creek. The prominently exposed quartz vein was impregnated with glistening free gold grains. This discovery ignited a prospecting frenzy in the surrounding area, resulting in a number of gold-bearing quartz veins being located.

The mineralized quartz veins occurring at Camp McKinney were typically white to bluish-white and were mineralized with pyrite, lesser sphalerite, galena, chalcopyrite and native gold. They varied from narrow stringers to over 10 feet in width. It is now known that the local major easterly trending, steeply dipping Cariboo quartz vein is developed as a cross-cutting structure in the northwesterly striking metamorphosed sedimentary sequence. This vein has been defined over a 3,000-foot trend and is the dominant structure within a wider mineralized system of sub-parallel and northeasterly striking quartz veins and veinlets. Widespread faulting has disrupted the vein systems in the camp locally with major offsets of 100 feet or more.

John Douglas was one of the early mine developers in 1888, and he wasted no time initiating an underground exploration program on the Douglas Mine property to define a very rich vein 150 feet below surface. High-grade ore was mined and stockpiled on the surface with the intention of setting up a mill. However, these plans were stymied as there was, as yet, no road along which to transport the equipment to the site. Underground exploration at the Cariboo Mine also intersected very rich ore on the Cariboo vein, and the owners were planning to set up a mill as soon as a wagon road was built from the U.S. border to the camp. By 1889, there were as many as 25 properties being actively explored or developed by underground methods. The properties located along the eastern and western extensions of the Cariboo vein were defining high-grade ore where the vein was locally up to 10 feet wide; these included the Amelia, Alice, Emma, Maple Leaf and Eureka claims.

In addition to the upbeat exploration and mining activity, the mining town of McKinney, named after Al McKinney and later renamed Camp McKinney, was being planned on a plateau centrally located about 1,800 feet south of the Cariboo vein discovery. Progress stalled in 1891 as road access to the camp was still not available, but eventually the main mining operation on the Cariboo vein prospered, and by 1901, with a population of 250, the town had reached its peak, boasting three general stores, a butcher, a drug store, five saloons, six hotels and a school.

One local mine, the Cariboo-Amelia, was well managed. The ore became richer with depth, and by 1896, a year and a half after start-up, approximately 18,000 tons of ore had been milled. The mine was paying a handsome dividend, and it was recognized as being the first lode mine in B.C. to achieve this distinc- tion. The mine workings extending for a mile along the Cariboo vein system were developed with three shafts and six levels to a depth of 530 feet. However, by the year 1900, much of the higher-grade ore was mined out. More seriously, a major fault had cut off the Cariboo vein to the east and to depth, and a program to locate the offset extension was unsuccessful. By 1903, the mine was essentially mining out the last of the available ore, and operations were suspended on December 31, 1903.

Total production from the Cariboo-Amelia mine from 1894 to 1903 was 123,457 tons milled, producing 65,581 ounces of gold and 5,359 ounces of silver. The average recovered grade for the ore was in excess of 0.56 oz/ton Au.

After closure, several companies attempted to explore for the “lost lead” or the faulted offset of the Cariboo vein. In 1939, Pioneer Gold Mines of B.C. dewatered the mine and drilled several surface and underground diamond drill holes to explore for the faulted extension. In the period leading up to 1958, W.E. McArthur of Greenwood acquired the property, drilled several holes from surface, and then optioned the property to H & W Mining Company Limited. This company dewatered the mine, extended the underground workings on the fifth level northward, and successfully intersected the faulted extension of the high-grade Cariboo vein.

Following some preparatory underground development by McKinney Gold Mines Ltd., mining recommenced to recover 4,370 tons of ore grading 1.20 oz/ ton Au and 1.70 oz/ton Ag in 1960. The ore was transported to the Trail smelter, and mining continued until 1962 with production from 1960 to 1962 totalling 11,292 tons; 12,001 ounces of gold and 14,261 ounces of silver were recovered. Following mine closure, the workings were allowed to flood.

As for Camp McKinney, much of the once-vibrant town was destroyed by a forest fire in 1919; a second forest fire in 1931 effectively completed the destruction.

Thanks to Giles Peatfield, Sue Dahlo, Linda Caron and Steve Cannon for co-ordinating and providing historic photographs of Rock Creek and Camp McKinney.