Mike Cathro literally grew up in mining camps. Both his parents worked in mining – his mom as a nurse and his dad, Bob, was a well-known exploration geologist and mining industry leader. From a young age, Cathro and his brothers spent their summers working in their dad’s field camps, burning garbage and washing dishes in places like Western Copper and Gold’s Casino project. Later, they helped with soil sampling and other field jobs.

It was these early experiences that shaped not only his 37-year career in mineral exploration and mining but also his outlook on life.

“My parents gave me a sense of adventure and instilled in me that I shouldn’t take myself too seriously,” he says. “My dad always encouraged me to get out of my comfort zone to try something different.” It’s advice that has served Cathro well.

Despite his early apprenticeship, Cathro didn’t plan on following his dad into the bush. It wasn’t until he was in his first geology course at Queen’s University that he realized he was actually really interested in geology and mining. After Queen’s, he continued studying for a master’s degree at the Colorado School of Mines – “mostly for the skiing,” he admits.

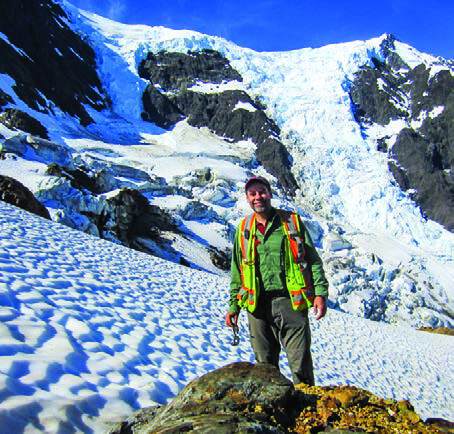

It was field work that hooked him. “I always enjoyed the bush work and I still do,” he says. “I liked the adventure of being out there, the energy of looking for something, being away from phones and the internet, the traffic and pace of the city.”

In his early days, he worked on projects in Yukon, Nevada, Australia and the South Pacific. “All the experiences gave me different perspectives of how things are done in different places, different deposits, different rocks,” he says. “They were all great experiences.”

Following the sage advice of his father, Cathro returned home to B.C. and stepped way out of his comfort zone for a guy who thrived on the field work, adventure and independence of an exploration geologist: he took a role in government. One of his first bosses, Geoff Freer, was by then assistant deputy minister of the B.C. Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources, and he offered Cathro a job.

“Going into an administrative role with government taught me a lot about dealing with people and fixing roadblocks to get things done,” he remembers.

For 17 years, he helped steer exploration and mine projects through the bureaucratic process: permitting, First Nations consultation, mine cleanup. It was often painfully slow, which contrasted with his job’s role in job creation. “There’s a lot of good people inside government,” says Cathro. “They work really hard, but from the exterior it’s never as easy as it should be.”

His time in government taught him the value of persistence, what makes people do what you want them to do and how important corporate culture is. “People skills are critical,” he says. “But they don’t teach them at geology school.”

In particular, he noticed the importance of a respectful corporate culture, especially in dealing with communities. “It can’t be one or two people,” he warns. “It has to come from the top, but also the on the-ground people who actually deliver it in person.”

Despite enjoying the challenging work, Cathro was pining for the field. In early 2008, he left behind the bureaucracy and took his new knowledge and experience to junior mining companies, both as a consultant and on staff. He liked the challenge of working with uranium – “probably the hardest mineral to develop” – and he joined Skeena Resources Limited as vice-president of operations.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Cathro joined the board of Geoscience BC. (Bob Cathro helped start AME’s Roundup conference, among other volunteer work; “he was a strong believer in giving back,” says Cathro.) Helping to push geological knowledge in the province is interesting and satisfying work, Cathro says. And it’s something he hopes to do more of.

In September, Cathro resigned from Skeena to spend more time travelling and skiing with his wife. He also wanted to get back in the field. He has a few projects he’s interested in exploring.

And that leads to the biggest thing Mike Cathro has learned in his career: “Individual prospectors and small companies can compete with much bigger companies,” he says, with the confidence of a man who has seen the industry from all sides. “Being small is an advantage. You can be smart and nimble and come up with unique ideas and opportunities. Being small doesn’t mean you have to take a back seat to the big guys.”