Introduction

The concept of “Fit for Work” (FFW) is critically important for both workers and employers. Employers are bound by legislation to maintain a safe and healthy work environment for all persons within the workplace by minimizing the risks of harm to individuals at the worksite, whether employees or contractors.

Workers can be considered FFW when they are not suffering from any type of impairment while at work. Impairment, under the BC occupational health and safety regulations, addresses physical, mental and substance use factors which may prevent a worker from safely performing their duties and/or which may create an undue risk to the worker or anyone else at a work site. FFW programming is focused on helping an employee perform their work activities safely, and to ensure that there are clear guidelines to communicate industry practice.

The Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia has the prime purpose to protect employees and all other persons from undue risks to their health and safety arising out of or in connection with activities at mines, including mineral exploration. Section 3.1.1 in Part 3 – Personnel Safety of the Code, specifies that “No person shall enter, remain, or be knowingly permitted to enter or remain in any mine if, in the opinion of management, his/her ability is so impaired as to endanger his/her health or safety, or that of another person”. This includes intoxicating liquor, cannabis, or illegal drugs, but does not include medical cannabis or industrial hemp.

This guidance document is designed to support members of the Association for Mineral Exploration (AME) with planning, designing, and implementing a Fit for Work program, and was developed by members of the Health & Safety Committee of AME.

Disclaimer

The information contained in this presentation is provided solely for informational purposes and may not reflect the most current legal developments and should therefore not be considered legal advice. The content of this guide should be considered in conjunction with the regulatory requirements stipulated in the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in British Columbia, or similar regulation in other jurisdictions, and in permit conditions. The legal landscape around these topics is subject to change and can vary between jurisdictions. As such, you should seek counsel for your own set of circumstances.

Under no circumstances shall AME or its affiliates, partners, suppliers, or licensors be liable for any indirect, incidental, or consequential outcomes arising out of or in connection with the use of the information contained in this presentation.

Pre-Employment

For the worker, FFW in the pre-hire setting is an opportunity to hear from the employer what the future work conditions will entail, and to outline the expectations and potential demands of the work, both physically and mentally. Certainly, there is a tendency for FFW to be thought of strictly in a medical context; however, there are other areas of “fitness” that should be considered.

In mineral exploration, given the working conditions which may be outdoors in difficult terrain or weather, and in remote locations with unusual life risks and residence in remote camps for extended periods, the impact on the individual can come in various ways. For example, psychological concerns can occur due to isolation from family and friends in an unfamiliar environment, as well as medical and/or physical risks.

Through the process of seriously examining and discussing FFW expectations, there should be no unpleasant surprises for the future worker when work commences. Moreover, it is a chance for the workers themselves to make a judgment whether they personally feel that the FFW expectations are workable for them, irrespective of what a medical expert may say.

During the conversation between potential workers and the employer, any concerns the future worker may have can be explored to address possible mitigations, such that the concern is adequately covered. For the worker, the way the employer addresses these concerns, either seriously or dismissively, may indicate as to whether it satisfies the possible worker. It also means that should an employer hide important aspects of the work that could relate to or negatively impact physical or mental health, then the worker may later have grounds for contesting the issues or even workplace health and safety or employment contract claims.

For the employer, determining the pre-hire FFW condition of a future worker is critical to ensure that the planned work can be done safely and productively without future conflict. The process of discussion of FFW prior to any formal offer of employment provides the employer some assurance that the worker can demonstrate through their personal assessment, and voluntarily divulge information on, any medical concerns the employer should know to ensure that the future worker is up to the job. As well as helping establish that the work can be completed as planned, this also reduces the chances of various negative consequences such as health and safety incidents – which may impact other workers as well and may cause high staff turnover and negative impacts on company operations. It can avoid the economic, reputational and staff morale issues ranging from worker’s compensation claims to employment contract litigation or dismissals.

The employer can determine their comfort with a worker’s FFW condition through various routes, all of which support one another, including:

- Observation during personal interviews.

- Perhaps supported by a written questionnaire and,

- Requesting voluntary discussion of medical history and their current alcohol or cannabis use (legal or otherwise).

- Medical (doctor or nurse) assessment.

- There are legal considerations around this that need to be considered but can be managed if the individual’s privacy rights are not impacted.

- References from previous employers.

Employment Medicals and Testing

There are serious legal, human rights and privacy issues around initial checking on a worker’s fitness for work, so caution must be taken.

An employer may ask the worker to voluntarily state if they have any issues that may cause concern given a description of the work duties and requirements. This description could be a brief document that lists the jobs and challenges – for example, a remote camp and the work involved. The employer may ask the worker to sign off on it and ask whether they have any concerns.

The employer may also ask for the worker to have a medical check where the doctor will sign off and certify that they are fit for work. This assessment may include the disclosure of prescription drugs the worker requires. The employer is not permitted to see the detailed result of the medical check; however, they may be notified that the worker has met the requirements of the medical check. If a medical assessment or test is required by an employer, the employer must ensure that the prospective employee does not pay for these services.

The medical professional will typically only report one of three conditions back to the employer:

- fit,

- unfit, or

- fit subject to work modifications.

Once the results of the medical check are made known, the employer can then approve the individual to be fit for work.

The employer should take sufficient effort to make a job’s physical effort reasonable if there are questions on whether employment can be refused on a specific basis in relation to fitness for work.

Worker Monitoring

Some large operations may have the internal medical capacity to test and monitor prospective and current workers; these medical staff will be able to provide observations on FFW on an ongoing basis. This means that an operation can better assess the situation of individual workers in specific jobs. The medical staff, through experience, will learn more of the conditions of work, and become more familiar with the individual workers. Smaller operations may need to consult a third-party company to assist in worker monitoring or testing.

Note that legislation and case law regarding drug and alcohol testing are evolving. It is highly recommended that employer seek legal advice before implementing a drug and alcohol testing program.

Elements of a Fit for Work Program

4.1 Mental Health

A mental health issue is defined as a health issue that can significantly affect how a person thinks, feels, behaves and interacts with other people. A mentally healthy workplace is one where workers are operating at their best physically, mentally, emotionally and socially.

In a Canadian survey, 20% of respondents said they had voluntarily left a previous job for mental health reasons – a number that increased to 50% for millennials (born 1981-1997) and 75% for Generation Z (born 1997-2015) employees. Losing an employee can cost an organization 1.5 to 2.5 times the departing employee’s annual salary with part of these costs related to hiring and training another worker (CAMH, 2020). In fact, mental health problems are a leading cause of illness and disability. The impact of mental health problems in the workplace has serious consequences not only for the individual but also for the productivity of the enterprise. Employee performance, rates of illness, absenteeism, accidents and staff turnover are all affected by workers’ mental health status (Harnois et al., 2000).

The purpose of this information is to act as an aid to establish, promote, and maintain the mental health and wellbeing of all workers through workplace practices, and encourage staff to take responsibility for their own mental health and wellbeing.

In terms of mental illness, as an employer, manager or supervisor you should:

- Identify possible workplace practices, actions, or incidents which may cause, or contribute to, the mental illness of workers.

- Take actions to eliminate or minimize these risks. Your OHS obligations extend to all workers at risk of mental health issues. Recognizing and promoting mental health is an essential part of creating a safe and healthy workplace. Managers and workers both have roles to play in building a safe and healthy work environment, one that will not create or exacerbate mental health problems and where workers with mental health issues are adequately supported.

Background

Research shows that developing a combined systems approach that incorporates both individual and organizational strategies is the most effective way to intervene in relation to job stress and to improve worker health as well as health behaviours.

Ideally, these strategies to address and manage mental health should then be integrated with broader OHS management processes. Risk factors that could cause physical or mental illness or injury should be systematically identified, assessed and controlled by eliminating or minimizing such risks.

Mental health problems, especially depression and anxiety, are common in the exploration community. While some people have a long-term mental illness, many may have mental illness for a relatively short time. Most of us will experience a mental health issue at some time in our lives or be in close contact with someone who has experienced mental illness.

Successful organizations and managers recognize the contributions made by a diverse workforce, including workers with mental illness. Diverse skills, abilities and creativity benefit the workplace by providing new and innovative ways of addressing challenges and meeting the needs of a similarly diverse workforce.

Developing and maintaining a mentally safe and healthy workplace can benefit both workers and employers by:

- Reducing the costs associated with worker absence from work, and high worker turnover

- Achieving greater worker loyalty and a higher return on training investment

- Minimizing stress levels and improving workplace morale

- Reducing OHS incidents

- Avoiding litigation and fines for breaches of health and safety laws

- Avoiding industrial disputes

It can also improve workplace productivity. Research shows that every dollar spent on identifying, supporting, and case-managing workers with mental health issues yields close to a 500% return in improved productivity through increased work output and reduced sick and other leave (Cowan, 2009).

Legislation

As an employer there are legal obligations in relation to the management of mental illness in the workplace.

- Ensuring Health and Safety: OHS legislation requires employers to ensure that the workplace is safe and healthy for all workers and does not cause ill health or aggravate existing conditions.

- Avoiding Discrimination: Disability discrimination legislation requires you to ensure your workplace does not discriminate against or harass workers with mental illness. Organizations are also required to make reasonable adjustments to meet the needs of workers with mental illness.

- Ensuring Privacy: Privacy legislation requires us to ensure personal information about a worker’s mental health status is not disclosed to anyone without that worker’s consent.

- Avoiding Adverse Actions: Organizations are also required to ensure the workplace does not take any adverse action against a worker because of their mental illness.

- In turn, all workers (including those with mental illness) are legally obliged to:

- Take reasonable care for their own health and safety

- Take reasonable care that their acts and omissions do not adversely affect the health or safety of others

- Cooperate with any reasonable instructions to ensure workplace health and safety

Implementation – Creating a Mentally Healthy Workplace

Providing a psychologically safe workplace that meets ever-evolving legal requirements is a challenge for employers. Purposeful leadership driving well-implemented policies and practices while following a set of guidelines can help employers meet those requirements.

The goal is to provide and sustain a workplace where there is strong support for all workers, with all workers being treated with respect and fairness. These goals can be achieved through five key phases:

1. Policy, Leadership and Commitment: Senior management can develop an appropriate policy and commit to its implementation.

2. Planning: Initially this involves development of a plan of action founded upon a baseline assessment of the hazards and risks arising from the workplace.

3. Implementation and Operation: Based on the planning outcomes, strategies and programs that will most benefit the workforce and the workplace should be implemented. This will guide how an organization should conduct itself on a day-to-day basis to avoid psychological harm and potential for legal liability. Policy without clear implementation guidelines will remain ineffective and may result in worker resentment and disillusionment.

4. Checking and Corrective Action: In this phase of a continual improvement cycle, the employer should assess (internally or via an external contractor) the overall process including the three previous phases. A determination is made on the completeness of the Policy, Leadership, and Commitment and Planning phases. Each strategic element included under the Implementation and Operation phase is assessed to determine how well it is functioning. Gaps are identified and remedies are prioritized.

5. Management Review: In this phase, an analysis of the outcomes from the Checking and Corrective Action phase is made to drive continual improvement and help ensure the overall process is effective and successful.

Guidelines for Creating a Mentally Healthy Workplace

Guideline #1

Create and sustain a culture in which workers at all levels feel safe and free to speak up about personal issues that may be affecting their job performance.

Managers and supervisors are trained and equipped to:

- Facilitate worker participation in conversations and meetings by removing obstacles to having an honest discussion. Obstacles include scheduling difficulties that leave work teams short and add time pressures.

- Create a level communication playing field by providing timely and relevant information for the worker before a significant conversation is held. In cases where a mental health issue might be involved, this might take the form of providing information (and reassurance to the extent possible) about the employer’s policies, programs, services and other resources.

- Ask what is on a person’s mind when they seem troubled without being intrusive or judgmental.

- Actively listen to what workers say without interrupting and without making assumptions about their motives or intentions. Encourage managers to explore the solutions offered by those who identify the problem before making any of their own suggestions.

- Develop plans of action in collaboration with those affected, when necessary, based on what has been heard and learned.

- Follow up and follow through on these plans and modify them when necessary (this is often a weak point in an otherwise sound approach).

Following this guideline can help to avoid complaints of discrimination based on mental disability and reduce absence or disability related to workplace stress or conflict, and at the same time allow managers and supervisors to develop more effective accommodations for those with a mental disability.

Guideline #2

Have the resources available to develop, implement and evaluate interpersonal performance of supervisors, managers and workers.

This can be done by various means including:

- Making it a routine practice to ask prospective candidates at hiring and for employee promotion to complete a self-assessment of, and reflection (for their eyes only) on, their interpersonal skills.

- Ask candidates for hiring and/or promotion to come prepared to discuss their thoughts about their own self-assessment (the employer would not normally see the completed assessments unless the potential or actual worker freely volunteers the information).

- When appropriate (e.g., at hiring), record candidates’ self-assessments (with their knowledge and understanding) and impress upon them that demonstration of interpersonal competence (or emotional intelligence, or communication skills – however you feel comfortable in describing the skill set) is part of the expectations that the employer has of them.

- Checking if candidates for hiring or promotion have a documented track record of positive leadership (if applicable). Design any interview questions and process to include assessment of interpersonal competence.

Three of the key elements of a worker’s interpersonal competence that should be assessed at a minimum are:

- Level of awareness of how they affect others and how others affect them

- Managers’ and supervisors’ ability to understand and accommodate the legitimate interests, claims and rights of their workers

- Concern for, and carefulness of the psychological well-being of others based on their awareness and understanding

Following this guideline assist in lowering the risk of legal consequences from negligent, reckless and intentional management behaviour that leads or contributes to mental injury. This type of behaviour includes harassment, bullying and even the careless and chronic imposition of excessive job demands.

Guideline #3

Be vigilant for and attend to early warning signs of conflict, worker distress and negative behaviour among workers.

An audit procedure to identify data or indicators that may help point to problem areas. Some indicators you may find on your own and in Employee Assistant Program (EAP) provider statistics, records and reports are:

- Patterns of short-term absence according to length of time away and reasons for absence. Mental health concerns are sometimes concealed in absences that are described primarily in physical health terms (migraines, stomach upsets, back problems, chronic fatigue syndrome, etc.)

- Insurance claims for long-term medical disability according to reason for absence

- Grievances and complaints to external bodies (arbitrators, human rights tribunals or officers)

- Internal complaints to Human Resources, whistleblower resources and/or OHS committee or personnel regarding harassment, discrimination, bullying, etc. (are they randomly distributed or is there a pattern?)

- Turnover trends and patterns

Guideline #4

Monitor the conduct of third-party service providers whose staff interact with your workers.

Require compliance and accountability according to your organization’s code of conduct. You cannot delegate your own duty of care to provide a psychologically safe workplace; however, following this guideline can help you avoid liability for the acts and omissions of other providers upon whom you may rely for provision of services to your workers.

To create a psychologically safe workplace, an organization can provide the following:

- Ongoing professional development training with:

- Structured discussion of workplace mental health issues

- Mental health and well-being site checklist to be conducted and reviewed annually

- Subscribe to WorkSafe BC Enews, which has a mental health and wellbeing component

- Employee Assistance Programs (EAP) in the workplace with:

- All sites offering an EAP provider to workers and managers

- An overall EAP strategy and regular review

- Quarterly review of global EAP trends

- Discussion related to EAP in OHS committee/staff meetings to bring up employees’ concerns

- Manager training with:

- Manager tool kits developed

- Health and safety coordinator and manager training

4.2 Drugs and Alcohol Awareness

This section deals with various aspects of impairment. Workplace impairment as an occupational health and safety issue is of concern to employers, workers and other stakeholders in BC. A guide is available through WorkSafe BC to provide employers with information on managing workplace impairment and developing an impairment policy.

- Impacts of Alcohol.

No group is immune from the harm of drugs and alcohol, but young and inexperienced workers tend to have more alcohol-related accidents at work than older and more experienced workers. In Canada, driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs is illegal and can lead to criminal prosecution.

Accidents at Work

The risks associated with alcohol may be increased when used in combination with other drugs. Alcohol can magnify the effects of sleeping pills, prescribed medicines, cold remedies and cannabis.

Impairment

Everyone knows that alcohol impairs a person both physically and mentally and that people under the influence of alcohol are dangerous while driving and when they are at work. A hangover can also seriously impair a person’s physical and mental performance and introduce fatigue, which is also a major contributor to workplace accidents.

Time to Sober up

In an average person, alcohol is metabolized at the rate of about 0.015% of blood alcohol concentration or BAC every hour. This means a person with a very high BAC of say 0.15 would take about 0.15 divided by 0.015 = 10 hours to have their BAC fall to 0.00. That is, they would need about 10 hours to sober up before they could go to work. It is very difficult to estimate how many drinks it takes to reach a certain BAC level because it is very different from person to person. It is each worker’s responsibility to manage the amount of alcohol they consume and the amount of time they leave themselves to get the appropriate amount of sleep to avoid fatigue. It is important that they are aware of how many drinks they have had and how many hours they have before work starts. Although people can control how high their BAC goes by drinking less, they cannot speed up their metabolism of alcohol. Drinking coffee, exercising or taking showers has no effect on alcohol metabolism.

- Impacts of Drugs.

The Workplace

The use of certain types of drugs and alcohol can significantly increase the chances of cardiac arrest/arrhythmia and death; it should also be noted that in several countries, the purchase and/or possession of even small quantities of drugs is punishable by law and can lead the individual to legal prosecution. The U.S. Department of Labor has reported that drug and alcohol abuse in the workplace causes 65 percent of on-the-job accidents and that 38 percent to 50 percent of all workers’ compensation claims are related to the abuse of alcohol or drugs in workplace. The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety indicates that the fact that some people use substances such as alcohol or illicit drugs, or that some people misuse prescription drugs is not new. The awareness that the use and abuse of substances may affect the workplace, just as the workplace may affect how a person uses substances is, however, increasing in acceptance. Many aspects of the workplace require alertness, and accurate and quick reflexes. Impairment to these qualities can cause incidents and interfere with the accuracy and efficiency of work.

Ways that problematic substance use may cause issues at work include:

- any impact on a person’s judgment, alertness, perception, motor coordination or emotional state that also impacts working safely or safety sensitive decisions

- after-effects of substance use (hangover, withdrawal) affecting job performance

- absenteeism, illness and/or reduced productivity

- preoccupation with obtaining and using substances while at work, interfering with attention and concentration

- illegal activities at work including selling illicit drugs to other employees

- psychological or stress-related effects due to substance use by a family member, friend or co-worker that affects another person’s job performance

As society has changed over the years and recreational drug use has become legal, access to drugs and acceptance of drug use is on the increase for some groups of our society. While the acceptance in these groups may have increased, the risk of harm is still present and ever increasing with the wider range of drugs available in addition to the risk of poisoning or overdose from opioids such as fentanyl. This can lead to frightening results in the workplace in the form of injuries and fatalities. Prescription, legal and illegal drugs can physically and mentally impair an individual, making it potentially unsafe for that individual to perform their work duties.

Cannabis

There are both potential therapeutic uses for and potential health risks of using cannabis (marijuana). Should an employee require cannabis under a doctor prescription, this should be revealed at pre-employment. The primary chemical responsible for the way your brain and body respond to cannabis is called delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). While it is used by some for therapeutic purposes, there are short- and long-term physical and mental health effects that can be harmful (Government of Canada, 2017).

- The general effects of can cannabis include:

- Depressing or slowing of the central nervous system

- Feelings of calmness and relaxation

- Talkativeness, increased pulse rate and reddening of the eyes

- Sleepiness and lethargy

- Decreased concentration and reaction time

- Distortion of sense of time and perception of sound and colour

- Impaired logical thinking and decreased ability to perform complex tasks (e.g., driving)

- Hallucinations

- Confusion and restlessness

- Anxiety, paranoia and panic

Effects can be felt within seconds to minutes of smoking, vaporizing, eating or dabbing cannabis. These effects can last up to 6 hours or longer. If you eat or drink cannabis, these effects can occur within 30 minutes to 2 hours and can last up to 12 hours or longer (Government of Canada, 2017).

Impairment can last for more than 24 hours after cannabis use (Leirer et al., 1991), well after other effects have faded causing people to be slow and lethargic with a decreased level of alertness. This can lead to an increase in mistakes, incidents and injuries. Combining alcohol with cannabis greatly increases the level of impairment and the risk of injury or death from accidents.

Amphetamines

The general effects of amphetamine use include:

- Stimulation and speeding up of the central nervous system

- An immediate increased alertness, which gradually wears off

- Increased confidence causing risk taking and accidents

- Talkativeness and hyperactivity

- Sleepiness at work due to lack of sleep caused by the drug

- Anxiety, irritability, suspiciousness and hostility

- Hallucinations and delusions

The duration of the effects of amphetamine use can last for between four and eight hours. An amphetamine hangover can last for between 12 hours and 2 days and include:

- Depression and drowsiness

- Loss of appetite

- Insomnia or sleeplessness

- Loss of concentration

These can all lead to an increase in mistakes, incidents and injuries.

Over-the-Counter and Prescription Drugs

It is the employee’s responsibility to manage all aspects of their over-the-counter or prescription drugs. The employer will be interested in drugs that will affect alertness, coordination, decision making and physical capacity (e.g., benzodiazepines or anything with codeine or similar substances). The employee is responsible for talking to their doctor or pharmacist and knowing the effects of any prescription medication over-the-counter drugs and if these are safe for work. Employees that are taking prescription drugs that could impair them at work are encouraged to inform their supervisor in writing.

- Self-Absenting

All workers have an opportunity and duty of care to self-absent themselves from work if they believe they are potentially or are impaired by alcohol or drugs. This avoids the risk of being tested and more importantly avoids placing themselves and their workmates at greater risk of injury. Self-absenteeism will be dealt with according to the normal procedures that relate to issues of work performance and absenteeism.

- Counselling Service

Most workplaces offer a professional and confidential counselling service via the Employee Assistance Program (EAP) for all employees, their direct family members and contractors to assist them with any issues in their work life, home life and drug or alcohol related issues. The EAP also provides trained personnel to listen, provide support and direction. These services are provided to help employees with potential problems before they get to be larger problems. Personnel can also safely disclose potential, perceived or actual alcohol or drug impairment issues via discussions with their Supervisor, Manager or Safety and Health Specialist.

4.3 Fatigue Management

Fatigue is a significant problem in modern industry, largely because of high demand jobs, long duty periods, disruption of circadian rhythms and accumulative sleep debt that are common in many industries. Fatigue is the result of integration of multiple factors such as time awake, time of day and workload. The full understanding of circadian biologic clock, dynamics of transient and cumulative sleep loss and recovery is required for effective management of workplace fatigue (Sadeghniiat-Haghighi et al., 2015).

Why you need a company fatigue management policy/procedure.

It is the employer’s responsibility to provide a safe work environment for all workers, and fatigue if not managed can lead to consequences ranging from a lack of productivity to serious injury, and even death. From a legislative standpoint, limits on Hours of Work are stated in section 1.5.1 of the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines in BC and in the BC Employment Standards Regulation (Part 7, Section 34 shows exemptions for certain exploration programs from hours of work and overtime requirements).

The Chief Inspector’s Directive BC Mineral and Coal Exploration Hours of Work allows for a variance from these hours for certain activities when a fatigue management plan is used.

What is fatigue?

Fatigue is a state of feeling tired, weary or sleepy that results from prolonged mental and physical work, extended periods of anxiety, exposure to harsh environment or loss of sleep (Sadeghniiat-Haghighi et al., 2015).

Fatigue can occur because of various factors that may be work-related, lifestyle-related or a combination of both. The management of workplace fatigue is a shared responsibility between management, supervisors and each employee.

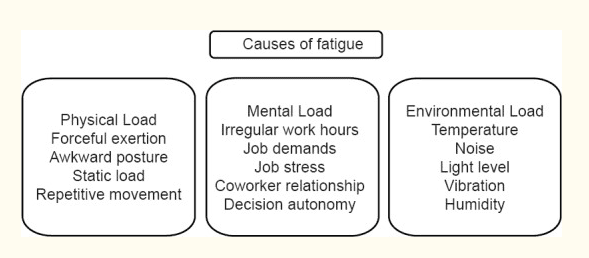

Causes of fatigue

There are many factors in both the workplace and out of workplace which can influence fatigue levels. The most important cause of fatigue is the lack of restorative sleep (Sadeghniiat-Haghighi et al., 2015).

What are the effects of fatigue?

The effects of fatigue decrease performance and productivity in the workplace and can potentially increase the rate of incidents, placing the fatigued worker and others in the workplace at increased risk.

The highest rate of catastrophic incidents is usually found among fatigue shift workers (Sadeghniiat-Haghighi et al., 2015).

While not all employees will be affected by fatigue in the same manner, studies have shown that fatigue may lead to:

- Reduced concentration

- Impaired coordination

- Compromised judgment

- Slower reaction times

An Australian study on the effects of sleep deprivation found that after 17-19 hours without sleep, performance on some tests was equivalent or worse than that at a blood alcohol content of 0.05%, the legal limit for driving in BC (Williamson and Feyer, 2000).

Potential areas of the highest risk when fatigued include operation of machinery and the operation of vehicles (both heavy and light). A lapse in judgment in any of these can have serious consequences, so it is important to be able to recognise the signs of fatigue in yourself and others.

All workers must know the signs of fatigue and how to recognize them, how fatigue can affect ability to safely perform their job, and what actions can be taken to manage fatigue.

Physical symptoms of fatigue include:

- Headaches and/or dizziness

- Muscle aches

- Breathing and digestive problems

- Tired eyes, blurred vision and difficulty keeping eyes open

- Distraction and difficulty in concentration

- Low motivation

- Nervousness

- Poor judgment, and reduced vigilance, possibly leading to risk-taking behaviour

- Slow motor skills resulting in slower reaction times and reflexes, and reduced hand-eye coordination and visual perception

- Falling asleep for less than a second to a few seconds and being unaware of this (micro-sleeps).

It is important to note that certain medications can increase drowsiness. Workers should disclose to their supervisors if they are taking any medications that could possibly impair their ability to do their job or operate a vehicle including cold and flu medication.

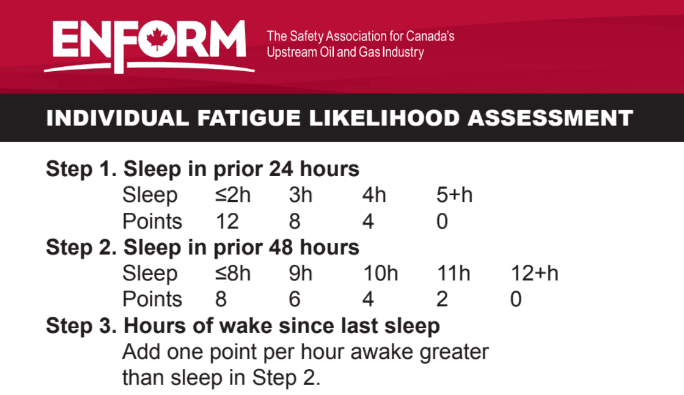

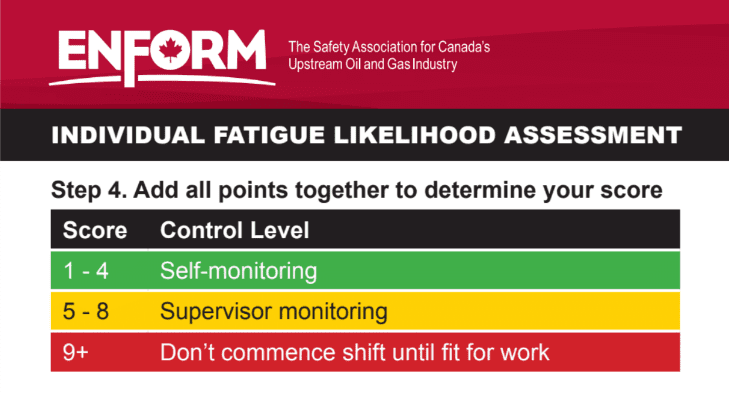

Fatigue management and controls

Fatigue is a problem that cannot be easily measured in the workplace. The type of instrument for fatigue measurement is depending on the decision that must be made by the organization. Measurement can determine one dimension of fatigue, usually severity of fatigue, or multiple dimensions. An example of an industry fatigue assessment is illustrated below:

Fatigue in the workplace should be managed to prevent any exposure, accidents or ill effects to the workers involved, the community and/or the environment. To manage these risks, the following basic risk management steps should be applied:

- Identify the hazard.

- Assess the risk.

- Identify controls.

- Implement controls.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the controls.

Minimize sleep loss

Both quantity and quality of sleep are vital to health and safety. It is recommended to have adequate resting time before a shift. Sleep is the only effective long-term strategy to prevent and manage fatigue. While tired muscles can recover with rest, the brain can only recover with sleep. The most beneficial sleep is a good night’s sleep taken in a single continuous period. The optimum amount of sleep varies for each person; with an adult generally requiring seven to eight hours of sleep daily. By recognizing the signs of fatigue, we can manage its impact on workers.

Naps during night shifts

Napping as a fatigue countermeasure has been found to be effective for shift workers. Naps with 30 minute or less duration provide measurable improvement in alertness and performance and decrease fatigue immediately upon waking (Folkard et at., 2005).

Good sleeping habits

When possible, keep a regular sleep/wake schedule to avoid circadian disruption; and reserve the bedroom for sleep and not for work, if possible. Tips include:

- Develop a comforting pre-sleep routine such as listening to the radio

- Avoid frequent naps during the day

- Get out of bed if there is a trouble with falling asleep

- Do not use caffeine, alcohol and cigarettes right before bedtime

- Make your bedroom quiet, totally dark and comfortable

Circadian adaptation

Appropriate timed exposure to bright light and administration of exogenous melatonin help to produce circadian adaptation to night work.

Work breaks

Every employee shall have necessary work breaks to avoid fatigue.

Job task management

Practice job rotation when working in a crew. Do not leave the most tedious or boring tasks to the end of the shift when an individual is likely to feel the drowsiest. Night shift workers are most sleepy around 4-5 a.m. If possible, schedule physically or mentally demanding tasks earlier in a work shift.

Conclusion

This guide is an introductory resource to Fit for Work (FFW). The nature of FFW is constantly evolving, and so is legislation. AME members are encouraged to consult the resources listed and are welcome to make any comments and suggestions for future tools to AME.

Have a safe day, every day.

Resources

BC Forest Safety

Fatigue Management.

https://www.bcforestsafe.org/resource/fatigue-management/

BC Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation

Occupational Health.

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/mineral-exploration-mining/health-safety/occupational-health

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health & Safety

Workplace Strategies: Risk of Impairment from Cannabis.

https://www.ccohs.ca/products/publications/Cannabis_pub_19.pdf

Energy Safety Canada

Fatigue Management Wallet Card.

https://www.energysafetycanada.com/getattachment/dfd1926d-0177-49db-b3ad-1be8d6342754/40400-315753-10-00065-fatiguesumposiumwalletcardcro.pdf

WorkSafeBC

Fatigue Impairment.

https://www.worksafebc.com/en/health-safety/hazards-exposures/fatigue-impairment

Enews

https://www.worksafebc.com/en/about-us/news-events/enews

WorkSafe Victoria, NSW, Australia.

Fatigue in mines: A handbook for earth resources industry.

https://content.api.worksafe.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-06/ISBN-Fatigue-in-mines-handbook-2017-06.pdf

References

CAMH. 2020. Workplace Mental Health – A Review and Recommendations. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/workplace-mental-health/workplacementalhealth-a-review-and-recommendations-pdf.pdf

Cowan G. 2009. Assisting the Return on Investment of Good Mental Health Practices. Best Practice in Managing Mental Health in the Workplace.

Energy Safety Canada. Fatigue Risk Management – A Program Development Guideline. Fatigue Management Wallet Card. https://www.energysafetycanada.com/getattachment/dfd1926d-0177-49db-b3ad-1be8d6342754/40400-315753-10-00065-fatiguesumposiumwalletcardcro.pdf

Folkard S., Lombardi D.A., Tucker P.T. 2005. Shiftwork: Safety, Sleepiness and Sleep. Industrial Health 43(1):20-3. DOI: 10.2486/indhealth.43.20

Government of Canada. 2017. Health Effects of Cannabis. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/campaigns/27-16-1808-Factsheet-Health-Effects-eng-web.pdf

Harnois G., Gabriel P. 2000. Mental Health and Work: Impact, Issues and Good Practices. Mental Health Policy and Service Development Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/712.pdf.

Leirer V. O. et al. (1991) Marijuana carry-over effects on aircraft pilot performance. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 62, 221–227. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1849400

Sadeghniiat-Haghighi K., and Yazdi Z. 2015. Fatigue management in the workplace. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015 Jan-Jun; 24(1): 12–17. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.160915. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4525425/

Williamson A.M., Feyer A.M. 2000. Moderate sleep deprivation produces impairments in cognitive and motor performance equivalent to legally prescribed levels of alcohol intoxication. Occup Environ Med 00 Oct;57(10):649-55. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.10.649.