Placer gold was supposedly first discovered in the Similkameen region of southwestern British Columbia as early as 1852 by trappers working for the Hudson’s Bay Co. They may have recognized the gold in Granite Creek, but these individuals were not interested in gold. However, news of the Similkameen gold discovery eventually spread and attracted many prospectors and Chinese miners to the area. Then most departed just as quickly as they arrived, off to join the excitement and lure of the Cariboo Gold Rush at Barkerville in the early 1860s. Some prospectors and Chinese miners stayed in the Similkameen and mined undisturbed along the Tulameen River for 25 years.

Then gold was discovered on Granite Creek, a northerly flowing tributary of the Tulameen River with the confluence about 12 miles west of Princeton. There are several versions of the discovery event, but Johnny Chance is credited with the discovery on July 5, 1885. Chance was a lazy roving cowboy who was with three partners, William Jenkins, Thomas Curry and E.M. Allison, herding a pack of horses along the Dewdney Trail when they camped at Granite Creek. Johnny was told to go out and hunt some game for dinner, so he loafed around and finally wandered down to the creek to rest. It was then that he noticed a bright sparkle in the gravel bed of the creek – it was a bean-sized gold nugget. He found another and another. He stuffed them in his buckskin pouch until it was full and strolled back to camp. The excited foursome staked and recorded the Discovery claim on July 8, 1885. The claim was located about one mile south of the mouth of Granite Creek.

Following the news of the Granite Creek discovery, it surfaced that William Briggs, Mike Sullivan and John Bromley had recovered coarse gold on Granite Creek in the fall of 1884. They were unable to stake a claim due to high water, but had intentions of staking their claim the following spring. However, there are no indications that they returned, and certainly no claims were recorded prior to Chance’s discovery.

News of this new gold strike ignited a wild stampede of miners, prospectors and fortune seekers from all directions to the promising creek. The rush was fuelled by glowing reports that the early miners were recovering $3 to $20 per day per man when gold was $16.75 per ounce. Men were coming from the Cariboo, Cassiar, Washington and California. Those coming from Vancouver and New Westminster travelled by train or steamship to Hope. There, they purchased supplies and trudged four to five days along the Dewdney and Hope trails to Princeton, and then a half-day trip to Granite Creek. Construction crews working on the Canadian Pacific Railway seized the opportunity to make a fortune and arrived at Granite Creek with great anticipation. However, with no placer mining experience, their dreams were dashed when they discovered they were only qualified to work for day wages with established miners.

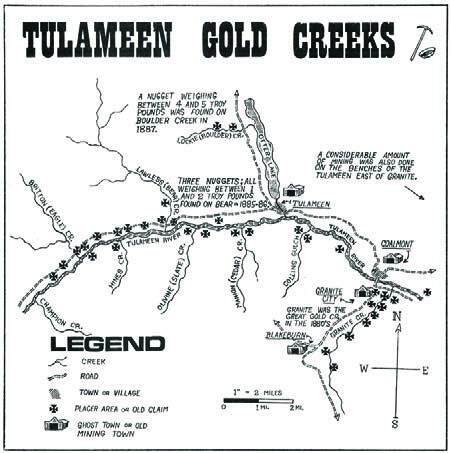

Granite Creek rapidly became a hive of activity as the miners established their claims along the five-mile stretch of prospective gold-bearing creek beds and banks. South of this stretch, the creek forks into two tributaries. There were many development challenges because the productive section of the creek is carved out as a deep V-shaped gorge through which water flow can reach devastating flood stages from sudden rainfalls and during the spring runoff. These floods can wash out flumes, wingdams and sluices. Also, parts of the banks were so steep that some miners built their cabins as much as 600 feet upslope from their claims, and scaled up and down the embankment by ropes.

By October 31, 1885, less than four months after Chance’s discovery, 34 companies and teams of miners were successfully recovering gold, and another 28 groups were at various stages of developing their claims. At this stage, approximately 5,400 ounces of gold valued at $90,000 were reported as recovered. This total was surely very conservative, as the Chinese miners were notorious for not reporting their actual gold recoveries. There were reports of several bonanza gold recoveries – one miner recovered 24 ounces in one afternoon with a rocker, then an eight-man crew washed 45 ounces in four hours. Working on his Discovery claim, Chance recovered almost 48 ounces in one day. Meanwhile, there were reports of new discoveries along the upper reaches of Granite Creek.

Flume and water wheel

First bridge over the Tulameen River, circa 1890

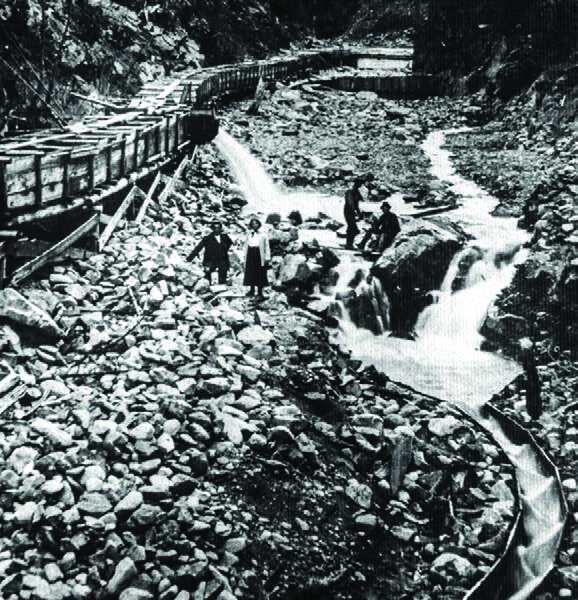

Map of Granite Creek vicinity

Interestingly, Chinese miners were mining along parts of the Similkameen and Tulameen rivers for years prior to Chance’s discovery, but they failed to find the riches of Granite Creek. The Chinese were very diligent and thorough miners, but they did little to no prospecting in search of new gold fields. If, by chance, they had discovered the gold along Granite Creek, they undoubtedly would have quietly worked the beds and benches without broadcasting their successes.

With the flurry of activity on Granite Creek, the scene was described as a stretch of several miles of swarming humanity, with horses and tents and campfires everywhere. Supplies, groceries and accommodations were urgently needed to serve the ever-growing numbers of men seeking their fortunes. A flat, terraced bench at the mouth and on the east bank of Granite Creek offered a suitable location for a townsite and staging centre for all the activities. Building and development on this rather confined 10-acre site commenced immediately, and by the end of October 1885, seven general stores, two restaurants, two liquor stores and a butcher shop were operating. A local sawmill provided the lumber for all this development.

The new townsite was named Granite City, also referred to as Granite Creek or simply Granite. One section of the townsite was developed and occupied by the Chinese, and another section became a suburb of tents. In the fall of 1885, it was estimated that 400 to 500 Caucasian and 150 to 200 Chinese miners were residing or camping at Granite City and in cabins or tents along Granite Creek.

The influx of people and construction at Granite City continued at a frenzied pace, and by 1886 there were about 40 houses; nine general stores; 14 hotels, saloons and restaurants; three bakers; two livery stables and eight pack-horse trains; a doctor; and an attorney. There was a jailhouse with no bars on the windows, but the windows were too small for jailbirds to squeeze through. G.C. Turnstall was appointed gold commissioner. Space for Granite City was very confined, and with the booming development there were almost 200 buildings crowded onto two main streets. Those two main drags – Granite Street and Government Street – were narrow and never more than trails of mud or dust.

In 1886, with a population of 2,000, Granite City was the fourth-largest city in British Columbia after Victoria, Vancouver and New Westminster. In every sense, Granite City was a flamboyant boomtown. It was a bustling hive of activity during the day, and at night it was a lively, crowded centre where the miners traded in their hard-earned gold nuggets for booze, women and gambling. And with all this excitement, there was absolutely no intention of building any churches.

Gold prices increased to $17.25 per ounce in 1886, and this coincided with the reported peak production of 10,722 ounces from Granite Creek. The actual gold production was probably significantly higher.

The miners on Granite Creek were noticing the presence of a hard, steel-grey metallic mineral associated with the gold in their panning and sluicing process. They called it white iron or white gold and, believing it was worthless, were throwing the material back into the creek. However, one Scandinavian prospector, Johanssen, kept his white gold in a pail with hopes that it might become valuable at a later date. Some Chinese miners also collected their white gold. Eventually, the white gold was identified as platinum, which, in 1886, was only $2.50 per ounce and shortly afterwards, $4 per ounce. Platinum purchasers at Granite City were buying platinum from some miners at $0.50 per ounce and, as a result, the purchasers were reaping a handsome return. Incidentally, Johanssen did not sell his cache of platinum, and when he left Granite City in 1907, he buried his 25-pound pail of platinum beside his cabin. He never returned to retrieve his cache; apparently, the pail of platinum, now worth about $460,000, is still buried somewhere in the ruins of Granite City. There were stories that the Chinese also buried their platinum collections and, decades later, returned to retrieve their hidden treasure.

Following the breakout year for gold production in 1886, miners, merchants and residents at Granite City were eagerly looking forward to another banner year in 1887. However, nature and weather conditions did not co-operate – spring runoff was exceptionally high and extended well into the summer, preventing the miners from working their claims. Some of the new miners to the district were low on cash and became very impatient with all the waiting, eventually leaving town. Some miners spent their spare time repairing wingdams and flumes in preparation for the startup. A few businesses closed their doors, and their buildings – originally constructed for $1,500 – were put up for sale for just $25. Meanwhile, the Chinese miners showed great patience and just waited for the favourable water conditions.

Eventually, in late July, water levels dropped to normal and the miners commenced operating. However, reports of good gold recoveries were mixed, as the miners complained of spotty, hit-and-miss targets, some of which were deeply buried. A number of disappointed miners who were hoping to make their fortunes overnight abandoned Granite Creek in frustration. By October, the high water levels of spring were too low for efficient operations. This was the last straw for many miners. It was proclaimed that the once- booming gold rush was now a bust. Gold production for 1887 dropped to 5,217 ounces valued at $90,000.

A few diehard miners continued to work their claims, with the successful ones averaging about $5 to $16 per day. Many Chinese miners were also working on ground that had been abandoned by earlier miners. Essentially, Granite Creek had become a salvage operation, although there were the odd cheerful occasions when two miners in two months recovered $500 worth of gold and platinum, including one gold nugget weighing 10.25 ounces. Several mining companies commenced tunnelling in the gravel to access pay streaks, some of which occurred along the bedrock interface. Other innovative procedures, such as the siphon method, and expensive water fluming and hydraulic mining were attempted in hopes of processing larger volumes of gravel. However, gold recoveries were rather limited in comparison with the massive amounts of effort. Between 1888 and 1891, gold recoveries on Granite Creek declined to between 338 and 565 ounces.

The steady decline of gold recoveries from Granite Creek signalled an accompanying slowdown for Granite City. Despite the gloomy outlook, travel to and from Granite City continued to improve as the construction of a wagon road from Spences Bridge, in the Nicola region, to Granite City was completed in 1893. The road was extended to Princeton and, by 1898, a stage coach provided weekly service to these centres. By this time, only a handful of Chinese miners and one or two small mining companies still persisted in the search for gold. Then disaster struck Granite City on April 4, 1907, when a huge fire reduced the town to ashes. There were a few halfhearted attempts to rebuild, but by then coal was the new buzzword and the town of Coalmont, established in 1911 across the Tulameen River from Granite City, was quickly becoming the centre of activity.

The many seasons of mining the benches and bars had ultimately exhausted the creek of its wealth. A final attempt to squeeze more gold from the gravel was initiated in 1928 to 1930 when a dredge was mobilized to the confluence of Granite Creek and Tulameen River; some gold was recovered, but the operation was hampered by the presence of big boulders and cemented gravel. This was effectively the last hurrah for the Granite Creek gold rush.

Today, a few deteriorating remains of cabins and buildings are all that mark the location of the old boomtown of Granite City.