Exploration geologist Donald Kennedy Mustard P.Eng. landed in Vancouver on June 6, 1965, with his wife, three young children and “the clothes we stood up in.” But he had a job, and within a week, he was out in the field. Over the following 50 years, Mustard left an indelible mark on mineral exploration in British Columbia and shaped policy and geoscience research across Canada.

Having celebrated his 96th birthday in September 2020, Mustard maintains a keen interest in exploration geology. Although he officially retired over 25 years ago, he served on several junior exploration companies’ boards well into his 90s.

Scottish-born Mustard left school at 17 and volunteered for military service during World War II. After officer training at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, he joined the Royal Armoured Corps and saw action in Burma. Postings in India and Egypt followed before returning to Scotland to finish his schooling.

Mustard enrolled in science at the University of Aberdeen. He selected a “fill-in course called geology that I really enjoyed,” he recalls. In 1952, Anglo American plc scooped up his entire graduating class and sent all nine newly minted geologists to South Africa.

Mustard’s first job was supervising five producing gold mines in South Africa’s East Witwatersrand Basin. His first day on the job was also his first time underground. “I went down a 10,000-foot shaft with five African miners, and I didn’t have any idea what to do,” he says. Squaring off against a dusty rock face with a faulting problem to solve, he simply started drawing what he saw.

Mustard found his feet and discovered additional gold in river channels under the main reef that extended mine life by five years. The next year, he moved to a large reconnaissance mapping program, where he and a colleague discovered what became one of the world’s largest vanadium deposits.

Anglo American promoted him, and he moved to East Africa to evaluate prospects there. One prospect was a goldfield in central Tanganyika (now Tanzania). The moment Mustard met the Italian operator’s daughter, he fell in love. Don and Iolanda (Mimi) were soon married, and as part of their honeymoon, he took his new wife to a mining conference in Johannesburg!

Later, Mustard resigned from Anglo American and managed his wife’s family’s goldfield in Tanganyika. Massive political unrest in the mid-1960s forced him and his family to flee. An Italian company hired him to travel to New York to discuss a phosphate mine he had visited in Tanzania. During a fateful conversation with the chief geologist of Amax Inc., Mustard negotiated his way to Vancouver, B.C.

As senior geologist with Amax, Mustard was introduced to the Canadian Cordillera while exploring for molybdenum near Pemberton.

“The bottom of the property was at 3,000 feet and the top was at 8,000 feet,” he recalls. “I went from doing horizontal geology on the plateaus of Africa to vertical geology in British Columbia!”

Mustard soon switched to copper exploration, managing teams doing generative work on B.C.’s porphyry copper deposits. “In the 1960s Vancouver was one of the world’s great centres of mineral exploration,” he remembers.

In 1972, BP plc approached him to form a minerals division. BP provided generous funds, a free hand to build a team of the finest people and instructions to look for “whatever you want.” He worked in this “dream” role at BP from 1972 until 1986.

The election of the New Democratic Party in 1972 propelled Mustard to join the B.C. & Yukon Chamber of Mines, as AME was then known. The incoming NDP introduced super royalties, a tax regime he says “turned most of B.C. ore into waste” and cancelled five proposed mines and a railway to Dease Lake.

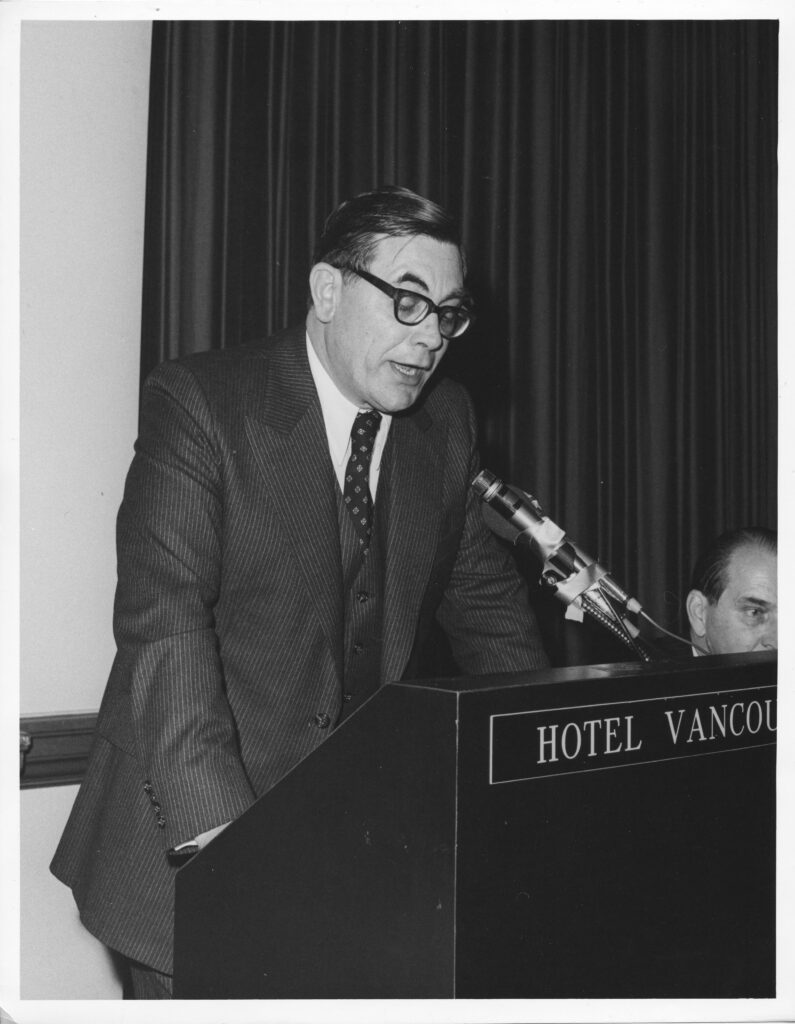

Mustard served as vice-president of “the Chamber” between 1976 and 1978, and as president from 1979 to 1981. The Chamber became an influential voice on national policy matters, and he travelled to Ottawa twice a year to meet with ministers. Soon after, he joined the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council grants committee as the sole industry representative amongst “mostly senior university people” to distribute $60 million in research funding annually.

Mustard’s most significant impact on Canadian geoscience came when he joined the Canadian Committee on the Dynamics and Evolution of the Lithosphere, which chose to fund the nationwide, multidisciplinary LITHOPROBE megaproject. LITHOPROBE studied the crust of the Canadian land mass and offshore margins to examine how the continent formed.

The first [seismic] line was in southern B.C., and we could actually see the subduction zone for the first time,” he says. This incredible research explored the driving forces behind the deposits we seek today. It was “a magnificent piece of science that hasn’t been matched anywhere,” he says.

Mustard also served on the Canadian Geoscience Council (now the Canadian Federation of Earth Sciences) board for six years and as its president in 1990-1991. In 1995, AME awarded Mustard the Gold Pan Award for his exceptional meritorious service to the mineral exploration community and, in 2008, he received the Distinguished Service Award from the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada for “his distinguished contributions to Canada’s minerals industry and this country’s geoscience community.

Mustard sees a key role for mineral explorers, whom he describes as “the best people in the world,” post-pandemic: “Canada will require substantial funds to recover and rebuild, and one of the major sources will be Canada’s world-class mining industry.”