In 1981, Vancouver was home to a vibrant minerals industry and venture capital market, and the outlook for geologists graduating from the University of British Columbia that year was bright. By mid1982, however, a severe recession hit, triggering an exodus of major companies and slashed exploration budgets. For the class of ’81, it was a memorable introduction to an industry where the only constant is change.

Fortunately, the industry was soon revitalized by the junior mining sector, which made impressive discoveries in the ’80s and early ’90s, notably Hemlo (gold), Lac de Gras (diamonds) and Voisey’s Bay (nickel copper-cobalt). Many geologists worked for juniors led by promoters such as Murray Pezim, or teams such as Bob Hunter and Bob Dickinson. Others formed their own juniors, typically financed by Peter Brown, the founder of Canaccord Genuity, with additional help from flow through-share funds.

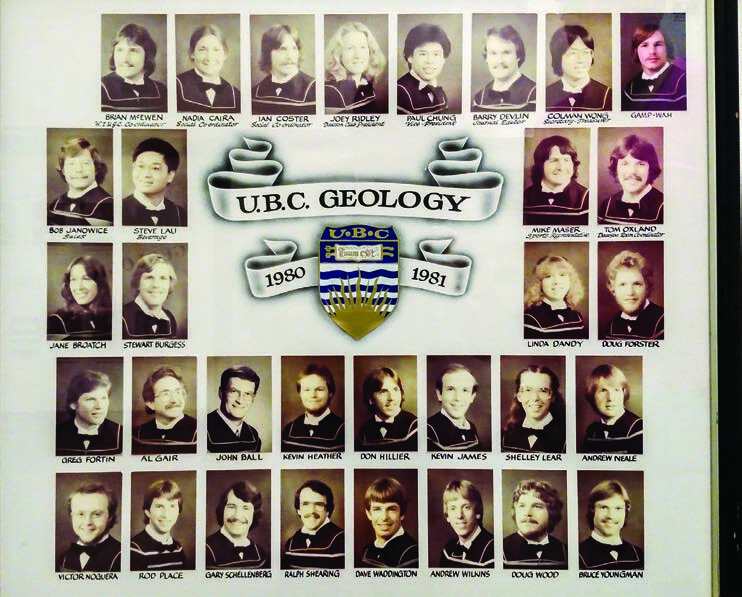

Joanne (Joey) Freeze worked with both junior and major companies before teaming up with a Peruvian geologist to form Candente Resource Corp. in the late 1990s. (Various assets were later spun off to form two other companies.) She says the industry is more mobile now and has more high-tech tools, but the business is still “all about the rocks” and unravelling the secrets they contain. “Computers help compile the data and model it, but they still need a human brain to imagine what [treasures] could be hiding.”

Freeze says she is surprised by the present gender balance of the industry (women comprise about 16 per cent of people in the industry), as women comprised 30 per cent of the class of ’81. “I don’t think there are barriers to women, just the lifestyle of exploration that isn’t so conducive to family life.”

Freeze’s classmate Doug Forster says the biggest change since he graduated is the global nature of the business. “In the 1980s, most UBC geology graduates worked on exploration projects in the Americas. Today, Canadian geologists work in almost every country in the world, and the North American capital markets raise funds for projects from Albania to Zambia.”

Forster gained valuable experience with Hunter Dickinson and was involved in development of the Golden Bear gold mine and the Mount Milligan and Kemess South copper-gold mines, all in B.C. Today, he is president and CEO of Newmarket Gold Inc., a recently formed, top-20 Canadian-listed gold company with three wholly owned Australian mines producing more than 200,000 ounces annually.

Forster says the biggest challenge facing the industry is keeping a competitive edge. “With the [ongoing] bear market for commodities, we are losing a number of our talented geologists and engineers, and there are fewer entrepreneurial capital-markets-focused businessmen to lead the next wave of deal-making when the commodity markets return.”

Nadia Caira, president of World Metals Inc., has worked continuously since 1981, albeit in 42 countries, with extended tenures in Indonesia, Central Asia, Mexico, Peru, Guyana, China and Tibet. “What other professions bring you to such exotic places?” she asks.

Caira sees opportunities for juniors to produce the strategic minerals powering new technologies, but worries where the funding and skilled workforce will come from, given that “uncertainty in all aspects of our industry is abundant, with no end in sight.”

Ralph Shearing and co-graduate Paul Chung formed their first public company in 1987. “Talk about trial by fire,” Shearing says. “We listed two months before ‘Black Monday’ (October 19) and learned a lot of hard and quick lessons about public markets.”

As president of Telson Resources, Shearing is pursuing development of the Tahuehueto polymetallic project in Mexico. “Access to capital for early-stage exploration is non-existent, and it is only recently (2015) that there seems to be a bit more activity with capital being directed to advanced projects and expansion of existing producing mines.”

Linda Dandy, a consultant and director of Sultan Minerals, says the two most notable changes over the past 35 years are technological advances and increased regulatory regimes. “In the good old days, one was dropped off by a helicopter in a camp in the remote arctic/mountain-top/lakeshore and communications were limited to a quasi-reliable SBX-11 radio. In the field, you got out your compass and tight chain or hip chain to lay out your grid. GPS was still a couple of decades away. Nothing was digital! Maps were hand-drafted, reports were typewritten and whiteout was a necessity.”

All that changed with the introduction of computers in the mid-1980s and rapid upgrades thereafter. “Now we have PCs and iPads and BlackBerrys in the field,” Dandy says.

Dandy gained B.C. experience at the Yellowjacket gold mine near Atlin and the Kena gold property near Nelson, and has noticed dramatic changes in permitting over time. She says 35 years ago, a notice of work was sent to the mines ministry seven days before starting a program. “Now it often takes several months to proceed through all the permitting requirements for that same program. And it seems each year or two additional items become regulatory, and additional applications and extended timeframes are now the norm. It sometimes feels like there are more regulators and inspectors than exploration geologists these days,” Dandy says. “At least the rocks have not changed over the years.”