The best part about being a mine inspector is the variety, from working with the RCMP on investigations to helicoptering into remote exploration sites, says Doug Flynn, senior inspector of mines for B.C.’s Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources. AME tracked down Flynn on his return from Pretium Resources’ Brucejack gold mine near Stewart where he spent a couple of September days witnessing the mine’s ramp-up to 3,800 tonnes per day, inspecting the exploration program and, in the evening, invigilating exams for blasting and shift boss certificates.

A mine inspector’s job involves developing and revising policy, conducting inspections and investigations and flagging health and safety infractions for review by the staff in Victoria. He provides expert advice in consultation with his colleagues, mostly geologists who occupy various positions such as permitting and health and safety inspector posts. Flynn is often away from his home in Smithers for several days at a time visiting sites in B.C.’s northwest quadrant, his territory all the way up to the Yukon border.

Flynn was impressed by Brucejack’s “gold-plated” approach to first aid, which includes highly trained on-site nurses and paramedics. “The biggest thing in our world is first aid because at virtually every mine or exploration site, people won’t get to a hospital in time if they are bleeding,” he says.

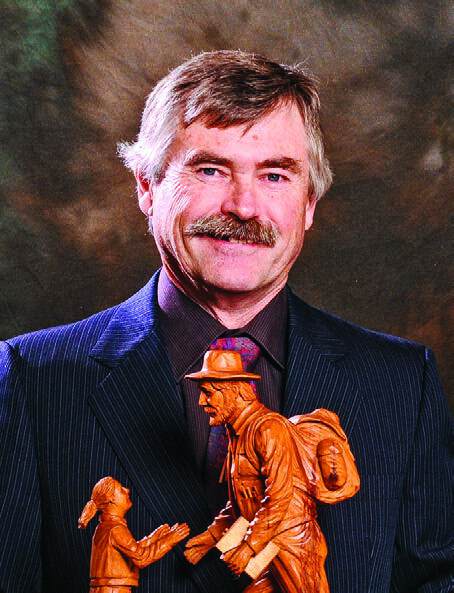

Safety is such a priority for Flynn that he was the first provincial employee to win AME’s David Barr Award in 2010. Gordon Campbell, the premier at the time, and former Prime Minister Jean Chretien were both on hand to congratulate him.

Flynn was born in Canmore, Alta., and discovered his passion for mining while working summers in the area’s coal mines. In the 1970s he was hired at Cominco’s Sullivan lead-zinc mine in Kimberley, B.C., after a completing a degree in mining engineering at the University of Alberta. He attributes his safety focus to his experiences working underground at Sullivan, where there was an average of about 35 lost time accidents a year. Sullivan closed in 2001.

There were sites that stand as examples of safety practices that have stood the test of time. There was a strong safety culture at the Kidd Creek copper-zinc underground mine in Ontario where Flynn worked next, because Charles Fogarty, the CEO of mine owner Texas Gulf Sulphur Company, made employee welfare a priority. Sadly, Fogarty died in a plane crash along with other Texas Gulf executives in 1981. Also, the Snip mine in B.C. that Cominco and Homestake operated during the 1990s was an exemplar of safety. “Snip started out with a management attitude that promoted a safe operation right at the start,” Flynn says. “The project was a fly-in site with no road access and during the summer they ran a hovercraft back and forth from Wrangell, Alaska. From a regulatory point of view, it was an easy site to regulate.” The Snip mine produced more than one million ounces at average grades of about 25 g/t gold and operated between 1991 and 1999, when it closed due to low gold prices.

During his industry career, Flynn noticed an inverse correlation between safety credentials and the frequency of lost-time accidents. Those who had the training were almost universally accident-free. “It was quite black and white, so all this money companies spend on mine rescue training pays off at the end of the day,” he says.

Naturally, his least favourite part of the job is dealing with fatalities. Since beginning work as a mine inspector in 1986, Flynn has investigated 19 fatal accidents. All but three occurred during the late 1980s after the Eskay Creek gold discovery touched off an exploration frenzy in B.C. Among the deaths were four young men drowned when their canoe overturned in Tatsamenie Lake during high winds in 1988.

When Flynn discovers an infraction, it can result in a mine closure, a revoked or withheld permit, an increase in the level of the reclamation bond or a fine. He had to close one operation temporarily, for instance, when the mine opened to much media fanfare but without a second exit from the underground workings required under the B.C. Mines Act.

Flynn says that his team is highly professional, with years of experience working in industry as engineers, foremen or mechanical bosses so they know what to look for when they visit a mine for inspection. “Don’t even think of coming to government until you have 10 to 15 years of industry experience,” he says. “Miners know when they are dealing with someone who doesn’t know what they’re talking about.”