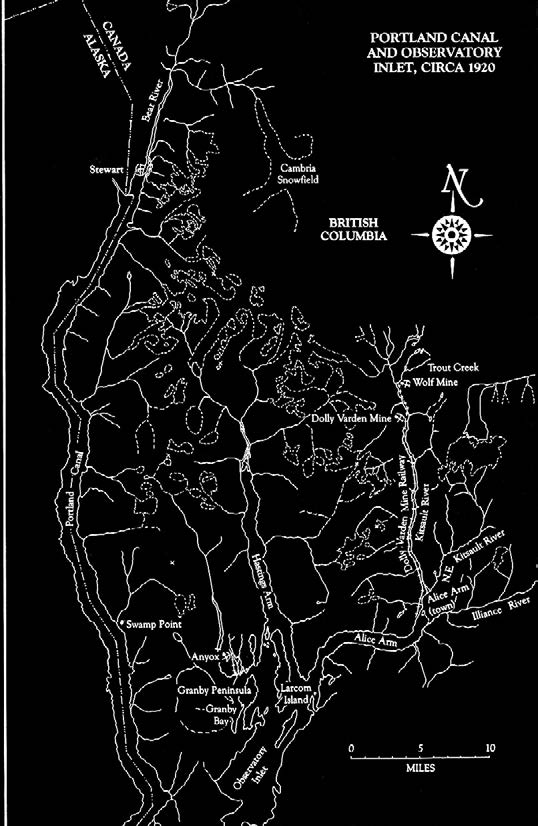

Following a very rich silver discovery made in 1910, the remote Alice Arm area at the northeast end of Observatory Inlet, 160 kilometres north of Prince Rupert in northwestern B.C., became a buzzing centre of prospecting, exploration and mining activity. More specifically, prospectors clambered their way up the heavily forested bluffs and rock walls along the Kitsault River, which drains into the head of the narrow Alice Arm Inlet.

The history of the earliest mineral discoveries actually dates back to the 19th century, when the Nisga’a First Nation camped at the Alice Arm site. They discovered molybdenite showing in this area and showed their discoveries to an Anglican missionary; some of these showings would eventually be developed as the Kitsault open pit molybdenum mine in 1967.

Frank Roundy was one of the first prospectors at Alice Arm, staking three precious metal claims in 1903. Then John Stark, the first settler at Alice Arm, staked two adjoining claims. This attracted the attention of other prospectors, and from 1907 to 1910 a number of precious metal and base metal prospects were discovered and staked along the Kitsault and Illiance rivers. The molybdenum showings were rediscovered and staked in 1907.

Prospecting and claim staking were generally confined to the lower reaches of the Kitsault River until 1910, when Scandinavian prospectors Ole Pearson, Ole Evindsen, K.L. Eik and E. Carlson arrived at Alice Arm. After several days prospecting along the rugged slopes and canyons further upstream along the Kitsault River, Eik and Carlson returned to Alice Arm for supplies while Pearson and Evindsen continued prospecting. It was then that Evindsen discovered what appeared to be a rich vein. Almost simultaneously, Pearson, about 75 feet away, discovered a large white boulder, prompting a vivid flashback of his dream the night before the prospecting expedition. In it, his late uncle prophesied the discovery of a big white exposure and Pearson’s subsequent wealth, and instructed his nephew to name the claim Dolly Varden, after the heroine of Charles Dickens’ novel, Barnaby Rudge. Accordingly, the four prospectors staked seven Dolly Varden claims on the steep west bank of the Kitsault River, 17 miles upriver from Alice Arm.

Early exploration on the claims exposed a 45-foot-wide body of quartz with pyrite, galena and minor chalcopyrite. Working conditions were challenging, as the steep terrain was densely forested and strewn with deadfall, and glacial till masked the underlying bedrock and mineralized zones. Transportation of supplies and equipment was a slow, back-breaking procedure until 1913, when a trail was hacked out to the claims from Alice Arm, though only the lower seven miles were passable with packhorses.

Shortly after the trail was built, the prospectors – faced with dwindling resources – gave one-fifth of their interest to Charlie Swanson in exchange for a grubstake. They then built a cabin and started driving an underground drift to expose the mineralized zone.

News of their discovery travelled, and other prospectors started staking around the Dolly Varden. In order to protect their interests, the four prospectors staked several other properties, including the promising Red Point copper and North Star silver claims, both about one mile north of the Dolly Varden. R.B. McGinnis, an engineer from San Francisco, came to examine the Red Point property, but was more impressed with the highgrade showings on the Dolly Varden and immediately leased the claims for $50,000. The original four prospectors and Swanson each received $10,000. His prophetical dream realized, Pearson returned to Sweden and bought a farm; the other three partners continued to work for McGinnis on the Dolly Varden project. Evindsen used his share of the payout to build the Alice Arm Hotel in 1916.

The trend of silver mineralization extended almost 20 miles northward from Alice Arm along the Kitsault River and partially eastward along the Illiance River. The Toric mineral claims on the east side of the Kitsault River and northeast of the Dolly Varden would eventually be developed by Torbrit Silver Mines, becoming the largest producer of the camp. The North Star claim, initially owned by three of the original Scandinavian prospectors, would be extensively explored by underground methods, but, despite high hopes, the mine only produced several hundred tons of high-grade ore. Other identified producers included the Experanza (which shipped 950 tons averaging 86.3 oz/ton Ag), LaRose, Wolf, Muskateer, Silver Horde, Climax, Moose and Lamb, David Copperfield and Tiger claims.

Early exploration was focused on prospecting, exposing and defining zones of mineralization with surface trenching, diamond drilling, underground tunnelling and raising. These zones, developed in volcanic rocks, varied from comparatively narrow, vein-like structures with pod-like bodies to massive deposits 40 feet (and occasionally up to 100 feet) wide and extending up to 500 feet in length. The largest quartz outcrop to be uncovered during the early days of the camp was on the Moose claim where a 150-foot-wide zone was exposed.

The mineralized zones are comprised of quartz, jasper, carbonate and locally barite with associated pyrite, galena, sphalerite, tetrahedrite, pyrargyrite, argentite and native silver. The principal silver-bearing ore minerals are galena, argentite and pyrargyrite, often referred to as ruby silver. Native silver characteristically occurs as thin ribbons and plates, and also as segmented veinlets. Interestingly, there is little to no gold associated with the silver rich deposits in the Dolly Varden camp. Early geologic studies suggested that the mode of occurrence for the Dolly Varden ore deposits is vein type; later they were referred to as structurally controlled replacement deposits, and, more recently, as stratiform volcanogenic deposits.

By 1915, a number of silver-rich zones of mineralization were being explored on many claims along the Kitsault River trend. Dolly Varden Mines Company, formed in the same year under Richard McGinnis’ leadership, was at the forefront of the exploration boom. A graded trail was constructed, along which packhorses could transport supplies and equipment from Alice to the site. A camp and assay lab were established at the property, and it was reported that thousands of tons of high-grade silver ore were defined along two underground levels.

McGinnis immediately optioned the Wolf property two miles north of the Dolly Varden on Trout Creek. Underground work on this property defined three zones of mineralization, of which the main zone on the surface was exposed over 60- to 80-foot widths and extended 500 feet in length. Silver grades for these zones were lower than Dolly Varden ore, but this did not deter McGinnis; he acquired the Wolf property for Dolly Varden Mines at a price of $50,000 in 1918.

Plans were being formulated to develop the Dolly Varden for production, but first, it was imperative that a reliable and cost-effective transportation system be established to transport the ore from the mine to Alice Arm. In 1916, McGinnis engaged Taylor Engineering Company to provide the design and cost estimate to construct a 15-mile narrow-gauge railway from Alice Arm to the Dolly Varden property. The initial cost estimate was $113,535; following a re-examination of the proposed route and reconsideration for more rock blasting and trestle construction, the estimate was revised to $160,222.

Taylor Engineering was contracted to build the railway and commenced construction in April 1917. The route followed the pack trail, but carving a railroad through steep canyon-like rock walls and talus slopes presented many challenges. Wartime shortages drove up the price for rails and other materials, and labour problems at the Vancouver and Prince Rupert docks delayed deliveries. Despite this, by October 1917, the first eight miles were complete and all bridges and trestles constructed from hand-hewn timbers were completed for 15 miles. Taylor Engineering was operated by Alfred Taylor, a young, resourceful and hard-working engineer. However, his inexperience in business led to financial problems for him and his firm during the final construction stages of the railway. Even with Granby Company’s bail-out funding on October 22, 1918, Taylor Engineering went into bankruptcy with the railway less than one mile from the Dolly Varden mine. Fortunately, Taylor Mining Company was reorganized and, on July 28, 1919, the first trainload of ore reached the wharf at Alice Arm for shipment by barge to Granby’s smelter at Anyox. The railway was later extended another two miles to the Wolf Mine.

With completion of the railway and a hydroelectric power plant on Trout Creek, the Dolly Varden mine – now operated by Taylor Mining Company, along with the railway – was in production. The mine was developed on three levels, and an aerial tramline installed to transfer the ore from the mine portal down to the railway siding. Mine production was maintained at 100 tons per day. During the mining, several small bonanza-grade native silver ore shoots were encountered; the super-rich ore was hand-picked and sacked for shipment to the smelter.

During the first year of production, the mine shipped 42 tons of super-high-grade ore grading 1,280 oz/ton Ag. Ore shipments from July 1919 until heavy winter snowfalls closed the railway totalled 6,709 tons averaging 63 oz/ton Ag. In 1920, production averaged 150 tons per day for a total of 28,037 tons grading about 30 oz/ton Ag. At this time, preliminary plans were on the drawing board to construct a concentrator for the Dolly Varden and Wolf mines, primarily to process lower-grade ore. With the persistently low silver price in 1921, only broken ore was salvaged and shipped to the smelter, totalling 1,874 tons grading 24.3 oz/ton Ag. Then the mine closed.

The financial issues that had previously plagued Taylor Engineering returned, and this time Taylor lost control of the property. The company was reorganized in the fall of 1922 under George Wingfield, and the property was promptly transferred to Goldfields Consolidated Mines Company, though the mine was not put back into operation. Neither was the railway, and although the tracks were available for hand-cars and speeders, the other mine operators in the camp were unable to ship large tonnages to Alice Arm. The Dolly Varden mine remained closed until 1935, when a small shipment of high-grade ore totalling 234 tons grading 271 oz/ton Ag was transported to Alice Arm by speeder and flatcar.

Over the years, a number of mining companies have evaluated the possibilities of reviving the Dolly Varden, Wolf and North Star properties, but this once-vibrant and promising mining venture has never reopened. In a nutshell, the demise of the Dolly Varden mine began with reckless spending on equipment by Taylor and construction cost over-runs, and was compounded by a labour strike and falling silver prices, resulting in bankruptcy. Huge exploration expenditures were incurred on the Wolf and North Star properties, but only a small tonnage of ore was ever mined from them.

Thanks to Nick Carter and Tom Schroeter for providing information and old photographs of this historic mining camp.