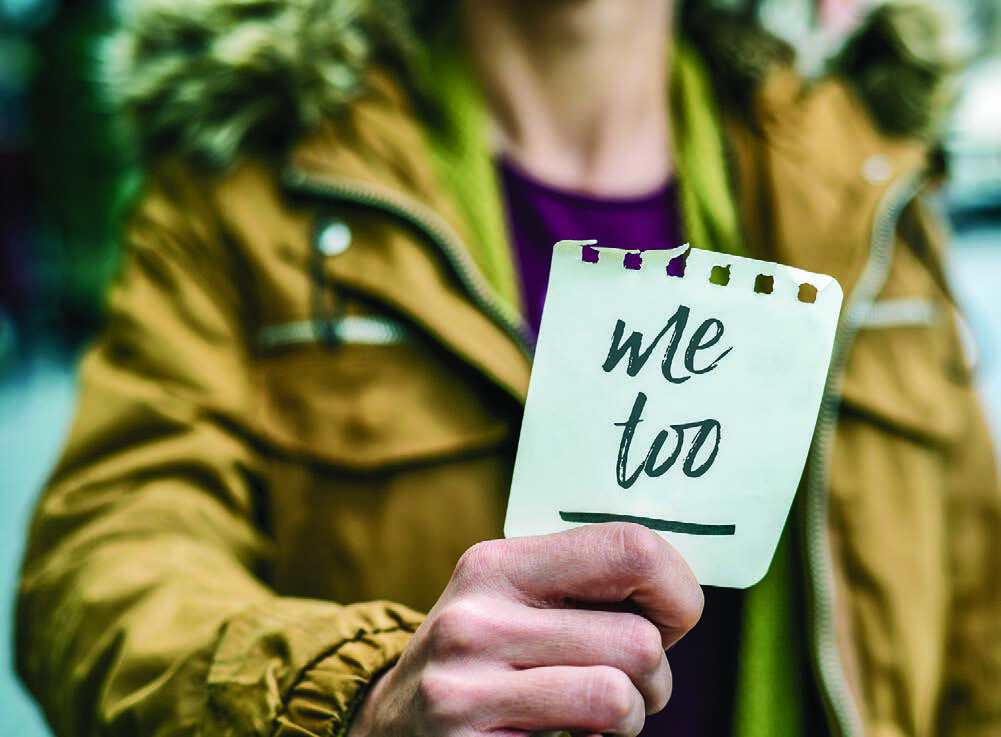

Hollywood’s red carpet is a long way from a remote exploration camp in northern British Columbia in more ways than one, but a chain of events in 2016 emphasized an upsetting similarity between the two: sexual assault and harassment happen, and the workplace culture deters victims from speaking up. The Me Too movement (or, as it appears so often in social media, #MeToo), a virtual global network that emboldens women and men to report sexual harassment and sexual assault, has forced a diverse range of industries to closely examine the accepted cultures that prevent people speaking up. What can the B.C. exploration sector learn from Me Too?

With mineral discovery rates on a steady decline and a generation of experienced explorers and mine developers set to retire from the industry over the next decade, the mineral exploration industry is facing an uphill battle to attract and retain new workers. Future discoveries will not come easily and require diverse teams with a wide range of backgrounds and specialist skills. They must be capable of thinking innovatively and collaboratively to find and responsibly extract increasingly complex and difficult deposits.

Sadly, exploration and mining workplaces are not attractive to a diverse range of people. Women, immigrants and Indigenous people are poorly represented. When people from these under-represented groups do enter the industry, they often face barriers, harassment and unconscious bias. Research published by the Mining Industry Human Resources Council in 2016 (prior to the emergence of Me Too) reported that 32 per cent of women said that they have experienced harassment, bullying or violence in their workplace in the last five years and 16 per cent of men said the same. Almost one in five women (18 per cent) who work in field settings reported that they had experienced harassment, bullying or violence in their workplace(s) monthly, weekly or daily in the past five years. Just as our attitudes toward health and safety have evolved over a generation, now is the time for workplace culture to evolve to be inclusive and safe for everyone.

The Me Too movement is accelerating this cultural shift toward equality, diversity and inclusion far beyond the entertainment industry where it was sparked in 2017 when actress Ashley Judd accused a high-profile Hollywood producer of sexual harassment. Her actions encouraged over a dozen colleagues and fellow victims come forward with similar accusations. In solidarity, actress Alyssa Milano encouraged people to post the words “#MeToo” on social media if they had also experienced sexual assault or harassment, to show how widespread and common this behaviour really is and help victims feel less alone. Millions of women and men responded, and the global Me Too movement was born.

Within a year of Judd’s actions, almost every industry on every continent was examining its workplace culture through the Me Too lens. According to Lisa Southern, lawyer at North Vancouver law firm Southern & Associates, the Me Too movement was one of two external drivers to have had a major impact on workplace culture in the B.C. resource industry in the last few years; the other was changes to WorkSafeBC legislation in 2015.

“Bullying and harassment were added to WorkSafeBC legislation in 2015, raising the profile of mental health injuries and toxic behaviours in the workplace,” says Southern, “Then, Me Too hit in 2017, forcing companies to again react and re-examine their culture.”

Southern’s law firm conducts workplace investigations on a variety of issues including harassment, workplace bullying, misconduct and privacy breaches. She is called in to conduct workplace investigations after a complaint has been brought or helps companies reduce the risk of incidents occurring through pre-emptive cultural scans and training. With over 20 years’ experience working with companies in the resource sector, she is uniquely placed to see larger trends.

“Me Too has shone a spotlight on issues that require society-wide change, ideally starting with school-aged children, but organisations can create safe, inclusive workplaces that provide a glimpse of what is possible when we work to eliminate toxic negative behaviour,” says Southern.

She recommends companies write a company code of conduct collaboratively with their employees and discuss it regularly during training and meetings. The code of conduct is a tool used with students in schools across B.C. and can be an effective means to engage employees to change behaviour and improve the culture at work. New worker orientations should include the code of conduct and emphasize that health and safety includes mental health.

“Everyone has a right to be safe at work,” says Southern. “It’s a concept that goes beyond physical safety, and includes mental health. A toxic work environment will have a negative impact on employees and ultimately the success of the organization.”