Uranium became a strategically important commodity in 1942 thanks to its military significance during the Second World War. As a result, an urgent plan was implemented to establish a large supply source in Canada.

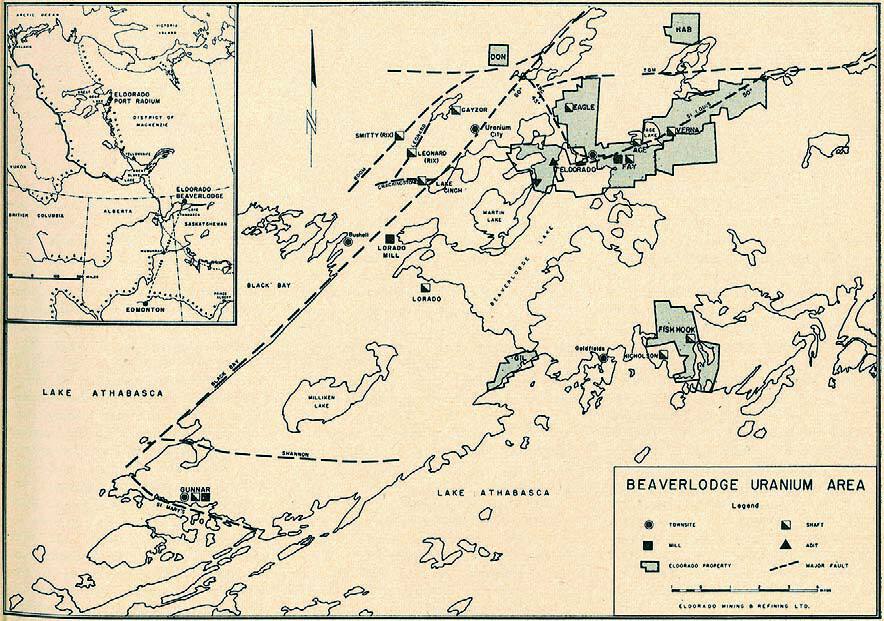

At the time, private prospectors and companies were banned from staking and mining radioactive minerals. A Crown corporation named Eldorado Mining and Refining Ltd. held the sole exploration rights for radioactive minerals. It initiated an intensive exploration program for uranium that extended across parts of Canada. This included re-examining the 1935 discovery of pitchblende, a uranium mineral, at the Nicholson property three kilometres east of Goldfields on the north shore of Athabasca Lake in northern Saskatchewan. Goldfields was the town site for the former Box gold mine operated by the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company from 1939 to 1942.

In 1946, systematic exploration programs by Eldorado’s geologists and prospectors using Geiger counters found more than 1,000 pitchblende showings around Goldfields and northward around Beaverlodge Lake, north of Athabasca Lake. The old town of Goldfields was reactivated as a base of operations for a short period.

The best pitchblende showings were discovered by Philip St. Louis on September 27, 1946, along a well-defined major fault zone at Ace Lake one kilometre northeast of Beaverlodge Lake. This major discovery along the St. Louis Fault would become the main orebodies for the Ace Fay mine for Eldorado.

The ban on private staking was lifted in 1948, and this triggered one of the largest claim-staking rushes in Canadian history. The historic Beaverlodge uranium rush was in high gear in and around Beaverlodge Lake and along the north shore of Athabasca Lake, with more than 100 companies and numerous prospectors combing the area in search of pitchblende.

Numerous new occurrences were discovered, and one of the most important was found by veteran prospectors Walter Blair and Albert Zeemel. In July 1952, they discovered radioactive boulders in muskeg near the south end of Crackingstone Pennisula, 25 kilometres southwest of Uranium City. This discovery would be developed as the Gunnar mine, the second-largest producer in the camp between 1955 and 1963.

Following the initial staking rush in 1948, a stampede of field programs involving geological mapping, trenching, drilling and underground exploration would assess the potential for the numerous properties. The field season was comparatively short, but the summer days were long, and it was a common sight to see float planes flying well into the evening. Geological consultants were in high demand, and it was common practice for the consultant to request payment in advance, as payment after the job was not always guaranteed.

Exploration activity was especially hectic from 1953 to 1955, during which time there were as many as 19 properties involved with shaft sinking and driving underground adits and drifts. The logistics to equip and service all these projects were challenging for the expeditors and float plane operators. McMurray Air Service, with its float plane base just south of Uranium City at Martin Lake, serviced many of the exploration camps.

By 1958, a total of 36 properties in the camp had been explored by underground methods; of these, 16 would become producing mines. The two largest mines to be developed were Eldorado Mining and Refining’s Ace-Fay-Verna mine and Gunnar Mining Limited’s Gunnar mine.

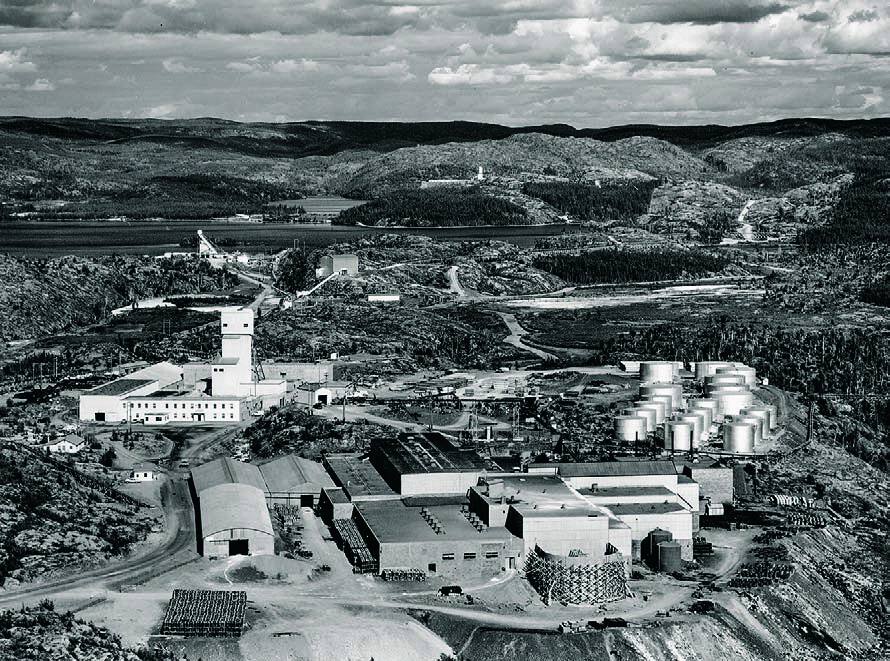

The Ace Fay-Verna mine was the first to begin production in 1953 with a treatment plant initially rated at 500 tons per day. The mill facilities were expanded to 2,000 tons per day by 1957. The Ace, Fay and Verna mines were developed by three shafts, and the underground workings were all connected by main haulage levels. The main Fay production shaft at the plant site facilities was developed to a depth of 1,250 metres and serviced by 24 levels. Most of the ore for these three mines was extracted from eight zones of mineralization occurring along an approximate three-kilometre trend of the St. Louis Fault. (In the 1970s, Eldorado also developed and mined high-grade ore from two smaller deposits, the Hab and Dubyna Lake, which occur several kilometres east of the Verna shaft.)

The Gunnar mine property advanced rapidly following the discovery of the radioactive boulders in 1952. Uranium mineralization was hosted in a steeply plunging 137-metre-wide pipe-like syenitic body that extended to a depth of 305 metres. A resource of four million tons grading 0.2 per cent U3O8 was estimated. The mine was initially developed by open pit; production commenced in September 1955 with an approximate mill throughput of 2,000 tons per day. As the open pit was being mined out, underground production was phased in starting in 1958 and continued until October 1963, when the ore body was depleted. A total of 5.5 million tons of ore grading 0.175 per cent U3O8 was milled.

Gunnar operated its own town site complete with a recreation centre. The mine site was isolated from Uranium City with no all-weather road connection except during the winter months, when an ice road across Athabasca Lake provided access to Uranium City.

Lorado Uranium Mines acquired a potentially promising property at the southwest end of Beaverlodge Lake in 1953. The company was able to define a small resource, but it was insufficient to support a milling facility. However, Lorado proceeded to construct a 500-ton-per-day custom milling facility in 1957, which, in addition to processing Lorado’s own mine production, would be capable of accepting ore from other mines in the camp. Several mines within convenient trucking distance of the Lorado mill commenced shipping ore there. These included the Lake Cinch mine producing 200 tons per day, the Cayzor Athabasca mine producing 150 tons per day, and the National Exploration mine producing 50 tons per day. Lorado sold its uranium quota contract in March 1960, and this sale also marked the end of production for the mill and the closure of the Lake Cinch and Cayzor mines.

Smaller, one-time ore shipments of between 500 and 2,000 tons were produced from several mom-and-pop-type operations. In keeping with the nuclear-age theme, several of these small mines had attractive catch all names such as Beta Gamma Mines, Meta Uranium, Pitch-Ore and Radiore Uranium. There were also a number of independent miners, prospectors and weekend rock hounds who shipped small tonnages, ranging from 10 to 2,000 tons, of hand-sorted high-grade ore from abandoned mine dumps, stockpiles and exploration trenches. Some of these small shipments were very rich, with grades up to 3.0 per cent U3O8.

The Eldorado milling facility also accepted custom ore. The Rix Athabasca mine two kilometres west of Uranium City mined and trucked 100 tons per day to Eldorado from 1954 to 1960. Other shipments were received from the Nicholson Mine at Goldfields, and the Eagle, ABC and National Exploration mines.

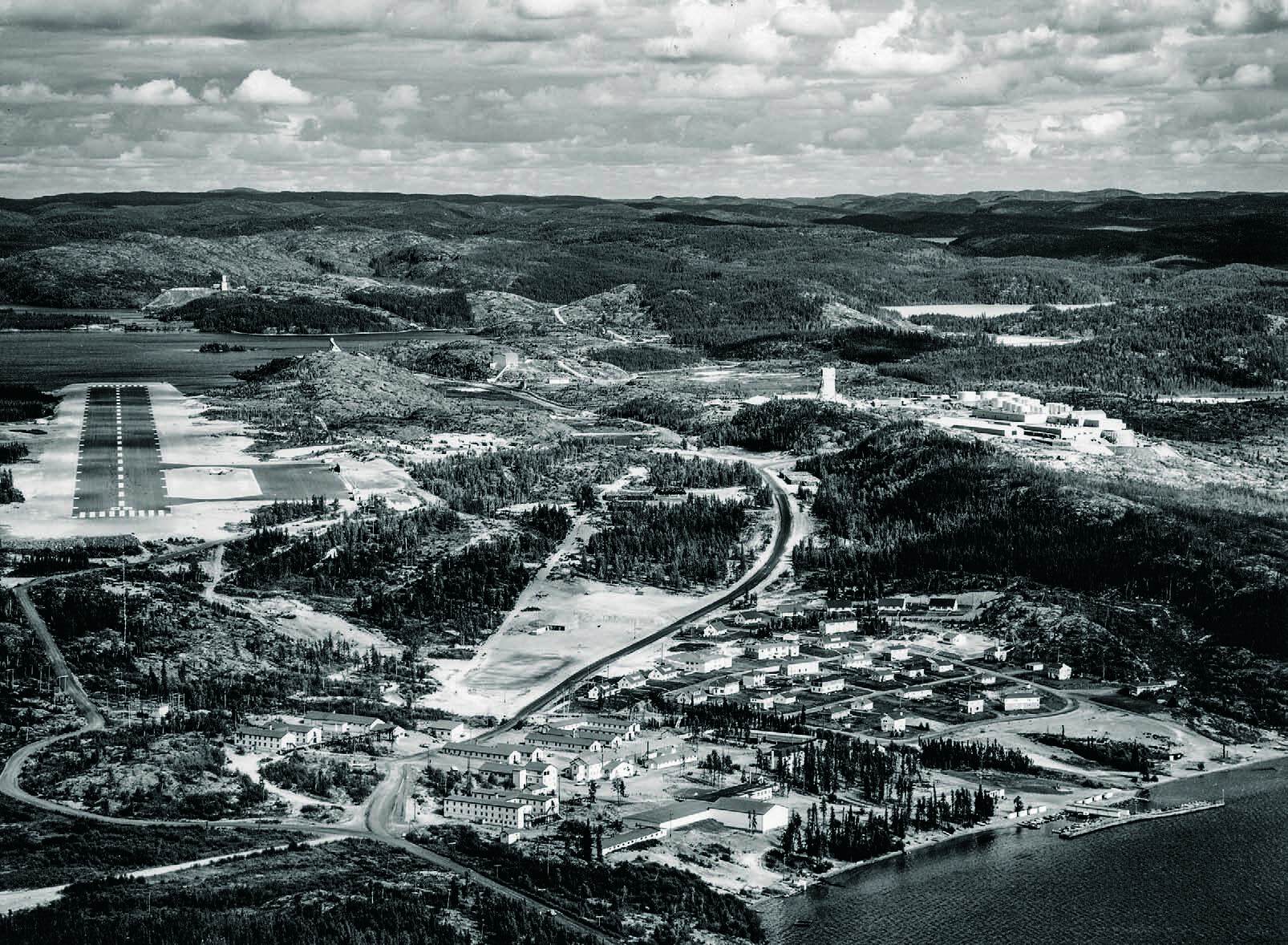

Uranium City was the central base of activity for the Beaverlodge uranium camp. The town was initially a tent city in 1951. From this beginning, it rapidly became Saskatchewan’s most northerly incorporated centre with a population of about 2,000 in the boom days of the 1950s. The thriving town expanded significantly in the 1960s when many of Eldorado Mining’s employees built their homes at Uranium City. Several of the first buildings were actually skidded across the ice on Athabasca Lake from Goldfields. Stores, schools, a bank, a hospital, a large liquor store, a curling rink and an ice arena were all available. The original Uranium City Hotel, with its spacious beer parlour and cocktail lounge, was very popular. The lounge was appropriately named The Big Stope, as the miners sat around the tables to boast about their huge tons of blasted ore. Beer shipments to the camp were transported by tug and barge from Fort McMurray after ice breakup in late June. As a result, beer in storage from the previous year’s shipments was often skunky by late spring, so the new stock of shipments was always welcomed. In order to get rid of the old stock, bartenders usually served it up in the later hours of the evening.

Uranium City – like many fast-growing boomtowns – experienced some devastating fires. The original hotel, the rebuilt hotel, one of the schools, and several businesses and homes were destroyed at different times. But the local people were resilient and most premises were rebuilt.

A regularly scheduled bus service to and from Uranium City was a convenient means of travel. A paved runway was constructed close to the town site and served as the airport for Eldorado’s own DC3 and DC4 aircraft as well as for Pacific Western Airlines. These aircraft provided daily service from Edmonton. After the closure of the Ace-Fay-Verna mine, the Eldorado town site and all service facilities were totally decommissioned; only the airstrip remains. All bulk freight, heavy equipment, fuel, lumber and construction material destined for the mining camp were transported by tug and barges from the railway terminus of Waterways near Fort McMurray down the Athabasca River and across Athabasca Lake to the port of Bushell 10 kilometres southwest of Uranium City. From Bushell, freight and supplies were trucked to the mines and towns. The Beaverlodge uranium camp was a vibrant mining camp during its heyday of prospecting, exploration and mine development. However, the discovery in 1968 of unconformity-related highgrade uranium deposits in the Athabasca Basin south of Athabasca Lake dramatically changed the exploration strategy and focus for uranium in Saskatchewan, and effectively cast a long shadow on any future opportunities for the Uranium City area. When Eldorado closed the Ace-Fay-Verna mine in 1982, it led to the economic collapse of Uranium City.

Between 1953 and 1982, 16 mines were put into production to produce over 28 million kilograms of U3O8 – 73 per cent of which was produced from the Eldorado-operated mines. Today, the camp is quiet.

Gary Delaney of the Saskatchewan Geological Survey is acknowledged for providing links to reports on the Beaverlodge uranium camp.