Mineral projects often have several operators over time and they’re all expected to be environmentally responsible. But first-on-theground exploration companies have the added responsibility of making a good first impression with limited resources. Many of them are turning to scalable best practices and tools to help add value to their projects and avoid conflicts with regulators and stakeholders.

“A scalable approach means you can be environmentally responsible no matter if you’re one person or a large company, and no matter the scale of the project,” says Silvana Costa, chair of AME BC ’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) committee and a co-ordinator of environmental and social responsibility for New Gold Inc.

No exploration project is without environmental risk, and as the industry has seen, minor issues can escalate to the point where multi-billion-dollar deposits are brutally devalued. Costa says small companies can do some of the same things as large companies to avoid such risks, albeit on a smaller scale and with a smaller budget.

As a first step, Costa recommends the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada’s e3 Plus: A Framework for Responsible Exploration as an easily accessible toolkit that small companies can use for guidance in the field. “Some juniors think it has too much information and is too complex, but even if they just stick to its basic principles, they should be able to do quite well.”

Allison Armstrong, director of lands and environment for Kaminak Gold, agrees that small companies can be environmentally proactive without breaking the bank. “One of the challenges of the past is that most consulting firms were used to doing environmental studies for advanced projects near production,” Armstrong says. “A small company had to take the largerstudies model and try to make it fit their project, which wasn’t easy to do. With the scalable approach, the studies would coincide with the level of work, and can be expanded as work progresses.”

As a former consultant with 14 years of permitting and environmental compliance experience, Armstrong encourages companies to start environmental baseline studies as early as possible, before drilling and work programs begin. Water quality studies and wildlife monitoring are great places to start, she adds, as these issues tend to attract the most public scrutiny – particularly in remote and northern areas.

“A scalable approach means that if you have one drill turning, you don’t go out and sample 20 lakes and streams, but you do sample the lake downstream of the rig,” Armstrong says. “With wildlife, you can put up sighting sheets and ask everyone to keep track of what they see and where, and fill in the sheets with the details.”

Armstrong says these low-cost practices make advanced environmental studies more robust, add information to government databases, and help companies manage risk.

“In the case of water sampling, you would have water quality information before and after work begins, and if someone makes a claim that your activities are affecting water quality, you’d be able to show that’s not the case.”

Armstrong cites the example of a company (not Kaminak) suspected of degrading water quality and causing caribou deaths. With data from three years of wildlife and water quality studies available for review, the company was able to quash the concerns of local communities (the caribou were found to have died from predators).

“When engaging with First Nations, you want to be able to stand up and show what you’re monitoring and measuring,” Armstrong says. “It’s an insurance policy.”

Kaminak has adopted a scalable approach to remediating soil-disturbed areas at its flagship Coffee gold project in Yukon’s White Gold district. Test plots were created to determine how specific indigenous plant seeds perform compared to natural revegetation, with the results expected to guide future reclamation plans.

Matthew Pickard, director of environment and community relations for Sabina Gold & Silver, says dialogue is an essential first step of environmental planning. “You have to know where you are, know the area, and know what people believe is important.”

Sabina has advanced its Back River gold project to the preliminary feasibility stage as a proposed open-pit/ underground operation. The project is located in the West Kitikmeot region of Nunavut, where cultural and social values are as important as the environment, and where community engagement is part of the permitting process.

Along with a series of open houses and public meetings, Sabina arranges site visits so local representatives can see for themselves what environmental measures are in place, or discuss issues and information with people they know on site. “We have to communicate effectively, frequently and in the proper language to develop relationships and build trust,” Pickard says.

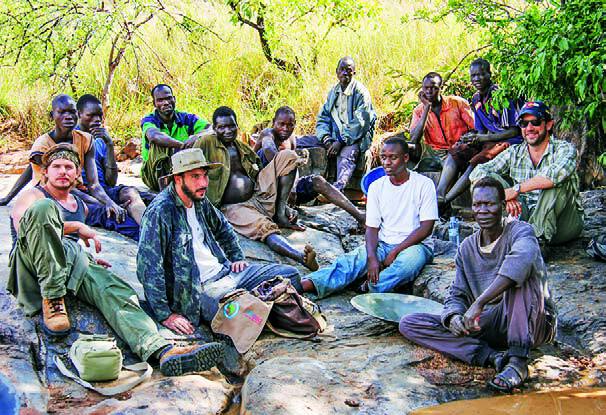

Gaining a social license to operate may be challenging in Canada, but it can be done with a commitment to CSR principles. Working in certain foreign countries is often a more daunting exercise, particularly in conflict areas of the world. Rakai Resources has taken a novel approach to gaining local support for its early-stage projects in Uganda, including in the Karamoja region now emerging from years of tribal strife.

Rakai has two founding partners – SeedRock Group, which has raised more than $300 million for global resource projects, and the Salama Shield Foundation, a non-governmental organization (NGO) with 20 years of experience in East Africa – and has seven properties of interest, including one active project in the Karamoja region. As an equity partner, the NGO would share in future profits and dividends.

CEO Stephen Burega says Rakai was attracted to Uganda because of its largely untapped geological potential and relatively stable political climate. Large companies are showing interest based on recent government geophysical surveys across the country, he adds, and a gold rush is opening up prospective regions.

“The country is overwhelmed by prospectors now,” Burega says. “People are picking up pans to try their hand at mining gold in streams and rivers. We’re not seeing a lot of mercury yet, but we’re afraid that may soon be the case.”

Rakai’s focus is artisanal gold-mining operations that will act as a pathfinder for both resource and social development. Many companies use small-scale artisanal mines as guides for large-scale exploration programs, often with the unintended consequence of creating social conflicts between local and outside parties.

“It’s a huge mistake to forget about artisanal mining communities,” Burega says. “We have conversations with indigenous people near our projects early, because we need to see what they want to see, and build relationships from there.”

In this case, artisanal miners want to move away from panning and breaking rock to mechanized methods, Burega says, but the problem is lack of capital and training. Rakai is involved in initiatives to provide training to artisanal miners and help them avoid environmental pitfalls often associated with small-scale mining practices.

Burega says Rakai’s strategy is to deploy capital to projects that ensure social and environmental progress as well as a return on investment. “These things are rarely thought about until the end of the [mine] cycle, or until a snag comes and leads to a slowdown. That style of CSR had to change, and that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Rakai is relatively new, with less than two years in Uganda, but Burega says the response to its partnership model and early engagement policy has been positive. “There’s a true ROI [return on investment] in building relationships up front.”